It is late afternoon in Mexico, two days before Palm Sunday, and it is the day that honours Nuestra Señora de los Dolores — Our Lady of Sorrows. All over town, San Miguel de Allende’s families and business owners have constructed altars dedicated to sadness: the sorrow of the Virgin Mary for the loss of her son. This ritual, Night of the Altars, is relatively unknown in much of Mexico but is one of the highlights of Holy Week in San Miguel.

As we amble north toward Parque Juarez in search of altars, we find no sign of them anywhere. The park is a haven of green — shadowed walkways, stone bridges over a narrow stream, giant overarching palms and wrought iron benches on wide, shady pathways. We find a bench under a laurel tree, cooled by the late afternoon breeze, and peruse the local newspaper for information in the hopes that we can find our way to some of these altars.

A few feet away, a girl waits. She is young, not more than fifteen. She checks her watch, folds her hands over and over. Her anxiety is palpable. On a bench next to us, an old man leans back, ankles crossed, arms folded. He’s watching the white egrets settling in the mesquite trees. Beside him is a copy of Jules Verne’s collected works — in Spanish. I hear music. Grand music. It fills the park with its magnificence, its sheer beauty, a musical score to this glorious afternoon. Then Sarah Brightman’s voice washes over us like shimmering glass. We stay and let the music carry us.

The young girl leaps to her feet then and and into the arms of the boy she has been waiting for as he strolls toward her. She wraps her arms around him and over his shoulder I see tears streaming down her face. Her long black hair is tangled in his arms. The old man closes his eyes and leans into the music and the slumbering afternoon. Families stroll by — mothers, fathers, and ragtag children, with grandmothers bringing up the rear. The grackles shriek from the pepper tree.

We wait until the music stops, then walk back to the parish church. At one of the street fountains, we find an altar in the making. A family is participating in its construction: a carpet made from a paste of ground grains and beans is pressed into the cement. A paste of blue is pressed into the centre to form a cross. Chamomile and fennel is strewn about and on the edge of the fountain, sour oranges — to represent the Virgin’s sorrows — pierced with golden flags that symbolize her joy at his resurrection. The Virgin’s humility, purity and beauty of body and soul are represented by the chamomile; the grain represents the resurrection and renewal of life and the fennel symbolizes the betrayal and abandonment of Jesus by his disciples.

But we still haven’t been able to find any of the altars. We sit for a while in the main square and watch the light drain from the sky. It’s busy now. Mexican families come from all over Mexico to San Miguel for Holy Week and pre-Easter festivities. In the bigger cities, many of the old traditions have been abandoned and families travel to the smaller pueblos like San Miguel to take part in these old rituals.

It’s dark when we head home and the lighted cross on top of the church looks as high as the moon. The wind is warm, the sky full of stars. As we turn toward our street, we realize that it is filled with people. Families. Teenagers. Babies tucked into rebozos. There is a silent rhythmic movement up the hill. We pass a fountain draped in purple ribbons — the purple we see everywhere today to honour the suffering of Mary. In one of the street fountains, water splashes over red and white roses, the Virgin enshrined in the centre. The crowd surges forward, gathers more followers. Then I remember what someone had told us: if you can’t find the altars, just follow the crowd. Even though there are hundreds of people moving slowly up the hill, the night is almost silent. The only sound I hear is a deep murmur like the sound of a slow-moving river. We drift together, a tide of individuals that has become one.

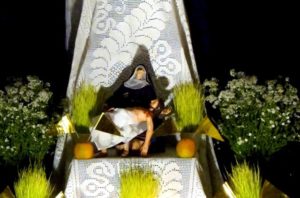

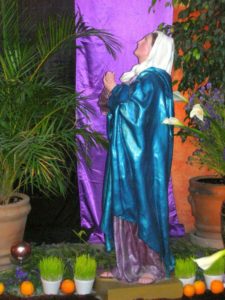

We begin to see the altars — in the doorway next to a taquería, in a fountain, in homes through grilled windows, in doorways, in courtyards, all lit by flickering candles and accompanied by soft music. We wend our way up one narrow alleyway just wide enough for two couples to pass. In the darkness we walk together, silently, amazed by what we see, by the dedication and the belief. Children gaze in wide-eyed wonder. Men and women both wipe tears from their eyes. Some just stand in silent amazement and look. Some pray.

The altars are elaborate; some families have spent the entire previous year planning and constructing them. All of them are dedicated to the Virgin Mother on this night but many are accompanied by scenes of the crucified Christ, the last supper, his betrayal and death. All the altars are strewn with fennel, chamomile, roses. And all have sour oranges pierced with the golden flags of hope and belief. At the altar houses, each family offers fruit drinks to symbolize the Virgin’s tears. In the blocked-off streets vendors sell tortillas, drinks, candy and ice cream. Sleepy children are scooped up and carried through the night. Although we are celebrating sorrow, it is the joy that lifts us and carries us along these warm, lamplit streets.

In the morning, as in mornings everywhere in Mexico, mops and buckets will come out and twig brooms will scrub the cobblestones clean. But for me, nothing will wash away the memory of Night of the Altars, a glorious serendipitous discovery, a sweet and unexpected gift for Easter.