Mexico on the surface is beautiful enough, but you have to dive to find its true treasures. Spanish is an indispensable tool for this, as it opens the door to readings and — more importantly — people you would not be able to connect with otherwise.

I have been in Mexico since 2003 when I came to teach English at Monterrey Tech in Toluca. My first years were spent like most other expats, establishing a daily routine and doing some traveling to the typical places. But pretty soon, they started looking the same, especially the small towns, all with churches, plazas and municipal buildings. Of course, they could not be so cookie-cutter, but without more information it was impossible to see what was important or different.

Needing to improve my reading ability in Spanish, I decided to start reading about the towns around me and to have something to show for that work, began transferring that information into articles in English Wikipedia. Coverage of Mexico in the site in 2007 was atrocious (today it is less-atrocious). The work not only provided a niche, but places I thought like knew, like Taxco, became completely new experiences all over again.

Encouraged, the handicrafts in the tourist markets drew my eye, only to find that most of these goods, which I had happily purchased previously, were either not of the area, were cheap knock-offs or both. Most of the better handicrafts are not in these markets at all. These markets are not much more than souvenir stands, as the typical tourist is looking for something curious, colorful, cheap and easy-to-purchase. There is nothing wrong with this, except to let tourists think that they are getting something authentic made by the person selling it.

Unfortunately, artisans are generally not the best salespeople in the world. They live in relative isolation because of geography, social status or both. Many sell only locally, and/or to resellers as they cannot or will not leave their home areas. More successful artisans, and those who make finer wares, such as silver, often have connected themselves to government or museum programs, but it really is just a problem of substituting one reseller for another. There is some hope however. Some artisans have banded together into cooperatives to bypass these systems.

Mexico does not lack for truly creative hands. What these artists lack is exposure to markets that can pay them what their creations are worth. Right or wrong, this means markets outside of Mexico for the most part. Which means the information about them is in English, and if available on the Internet, even better. I have spent more than 11 years on Wikipedia, and almost all the articles on Mexican handicrafts and folk art are my work.

Creating these articles has been a joy, not only reading about these products but learning about the people who create them. Getting the needed photos has meant traveling to little towns, having experiences like eating in a small adobe home in Xochistlahuaca, Guerrero food prepared by a grandmother who spoke only Amuzgo. The best food in Mexico is prepared in these situations.

Wikipedia served as my apprenticeship program, but it also taught me that there is so much ground left uncovered. If done right, Wikipedia articles can have only information that is already published in the traditional media. Unfortunately, scandals sell more papers than information about poor people doing great things with next to nothing. This was the idea behind two new projects, the blog Creative Hands of Mexico, now also a column in the Vallarta Tribune and the book Mexican cartonería.

Basically cartonería is papier mache, though Mexican artisans do not like to call it that. However, it is the appropriate Spanish term because Mexican papier mache products have a history and cultural significance all their own. Very little has been written on this craft (in a field lacking documentation in general) because it has the distinct disadvantage of developing and maintaining its presence in areas that are not known to tourists. By far, it is of greatest importance in Mexico City, which only recently has pushed to become a destination instead of just an airport to change planes on the way to Cancun. It remains to be seen if the city can succeed in getting people to stay, despite its reputation for crime (which is wholly exaggerated, especially in the areas attractive for tourists).

Almost everyone is aware of piñatas, thanks in part to Disney in the mid-20th century. Today, most of these are made with paper and paste. However, there are a number of other products made with the technique, almost all of which are tied to one kind of festival/holiday or another. Skulls and skeletal figures are made for Day of the Dead, effigies of Judas as a devil are made to be “burned” (really exploded) on Holy Saturday, bull figures loaded with fireworks are set off saint’s days, and much more.

All these traditional objects are still made, but the craft has expanded from here. It is not possible to talk about cartonería without talking about Pedro Linares. In the mid 20th century, he developed a new form called alebrijes from his Judas effigies, giving them more devilish and fantastic appearances until they became an art form in their own right. This was the first of decorative or artistic cartonería. These figures have become very important in the Mexican psyche in the past decades, and have become introduced to the world through the Disney movie Coco.

Just about all documentation on cartonería stops with Pedro Linares, who died in 1992. His family continues the tradition he set and has become something of the standard among many collectors and institutions. However, there has been so much innovation in cartonería since that time that is not documented either in English or Spanish, and is often done by people who are new to the craft. Innovation is a double-edged sword in Mexican handcrafts. To be authentic, there has to be a link to the past, either in theme, technique or a family history of making the product. Things that are too new, and too “disconnected,” such as the work of alebrije maker Susana Buyo from Argentina in the 1990s and 2000s, were not accepted by various circles even if many of her ideas have been proven to be ahead of her time.

When innovation does succeed, it makes a large impact – literally, in the case of giant altars and figures for Day of the Dead, principally in Mexico City and some extent, Puebla. Altars have grown to over take entire plazas and images of skeletons and figures from history and Mexican culture have grown up to ten meters high. Similarly, giant alebrijes take front-and-center during the annual Alebrije Parade sponsored by the Museo de Arte Popular in Mexico City.

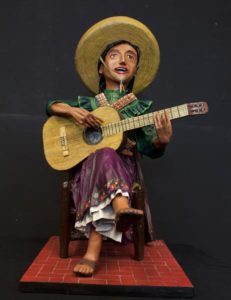

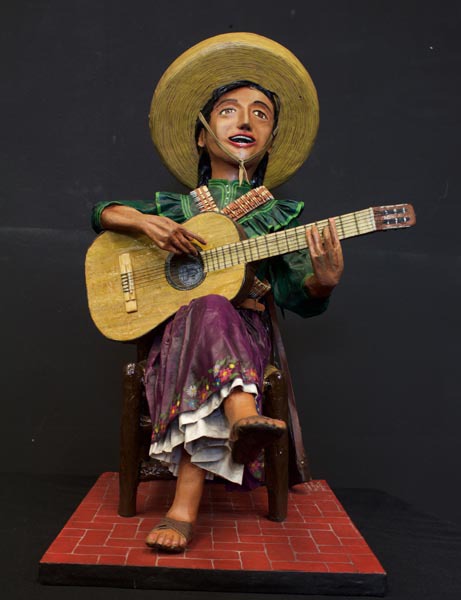

As cartoneros move into more decorative pieces, new themes are emerging in their work, such as scenes of daily life (folkloric and otherwise), nativity scenes and other religious imagery, giant puppets accompanying wedding parties, skeletons depicting modern life, and truly artistic works that one is hard-pressed to believe is “just paper.”

Cartoneria is growing, both taking back areas in which it had disappeared and being introduced to areas in the far north and south which did not have the craft in the first place. This means artisans new to the craft, who may not feel as tradition-bound as those in the center of the country. This is not without its controversies, especially from the few family-based generational workshops that still exist in Mexico City and Celaya, Guanajuato. However, this new blood seems to be bringing in a new perspective on Mexican culture, long overdue for recognition. The publication of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta is an important step in giving the craft and its artisans the attention they deserve.