Gold-colored walls line the main street through Santa María del Oro, Nayarit. Bumping along the cobblestones in our camper-van, we are following in the footsteps of the Spanish conquistadors. In 1504, the nephew of Hernán Cortés, Franciso Cortés de San Buenaventura came here, in search of gold. In 1530, the renegade conquistador, Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán seized control of the region. When he ruthlessly destroyed the native population, Nuño Beltrán became known as ‘Bloody’ Guzmán. Later, Guzmán appointed himself the first governor of the Province of New Galicia and established a capital at Santiago de Compostela, Nayarit. But in 1536, the viceroy had Guzmán arrested and sent back to Spain in chains. There, he was ordered to send seven special statues to the church in Santa María del Oro, in restitution for those he had harmed. One of these venerated statues still stands above the altar in the colonial church of La Expiración.

The atrocities of the conquest were followed quickly by the introduction of Christianity by the Franciscans. They founded Santa María del Oro, in a small valley below the wide plateau between Tepic and Guadalajara. The original town once bustled with gold mining activity where the village of El Real lies today. But when the mines expired but 1594, the town moved up to the plateau. In the centuries that followed, the hacienda system grew and controlled the region’s economy. After the Mexican revolution redistributed the land early in the twentieth century, the local economy continued to revolve around agriculture.

In our last two snow-bird migrations to Mexico from Canada, my husband, Bill Arbon and I always visit Santa Maria del Oro. After nearly 5000 miles of highway driving we are relieved to reach this tranquil town. Here we can relax on white benches in the plaza and watch a rural town in action. Ranchers and their workers rumble into town in trucks, from fields of cane and cattle. Town’s people climb the stairs into the government municipio or linger, chatting on the steps. Others are shopping in the stores scattered around the plaza. Old and young rest, visiting on benches under trimmed trees. Uniformed schoolgirls stride across the square. Women toting children and grocery bags, pause to adjust their load.

Although Santa María del Oro is small, all of life’s basic necessities may be found here. Near the central plaza are located, pharmacies, grocery stores, a video rental club, beauty parlor and a car parts with car wash at Lerdo #28 owned and operated by José Portugal who speaks excellent English. The few small restaurants include the La Parroquia near the old church and La Cocina Económica in front of the public The shopping buzz gets a little louder on Monday, when the weekly tianguis or street market arrives. As of January 2002 the nearest internet café was still in the capital city of Tepic, a half hour drive away.

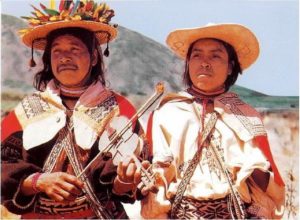

Occasionally Huichol natives, often in traditional costume, migrate through the town. They travel from their villages in the remote mountain valleys, in search of seasonal work. Today, the dark eyes of two Huicholes search us, the newest gringos in town. Perhaps they sense that, like the conquistadors, we too, search for gold. But of the kind we find in good people and the natural beauty of their land.

The most important holidays in Santa María del Oro are Easter week and the fiesta for Our Lord of the Ascension in May. Along with the Christian celebrations, there is an annual fair with mechanical rides, fireworks, a parade with floats and beauty queens, dances and a rodeo. Other national holidays, like Independance Day and the Mexican Revolution, are also celebrated with parades. There is a traditional New Year’s Eve Ball and a rodeo on January 1st.

This trip in October 2001, we are seeking a small crater lake, five miles past town. Shortly after leaving town, we stop at a viewpoint over-looking La Laguna de Santa María del Oro. The lake gleams like a blue jewel in a big green bowl. To reach the one-mile wide crater (2km) lake, the paved road twists downwards. Drivers be wary, the road is narrow and steep and without margins. A former governor of Nayarit had the road constructed in order to build his lakeside villa. When temperatures soar on the plateau above, the valley remains slightly cooler below. La Laguna is popular as a day-trip or weekend place for city dwellers from Tepic and Guadalajara. They enjoy the dozen lakeside restaurants and several choices of accommodations. These range from the five-star, wooden cabins of Resort of Santa María to the casitas, rooms and campsites of Bungalows Koala and RV Campground.

Bill and I choose a campsite at the Bungalows Koala. The canopy of trees overhead quivers with bird flight and song. Sometimes, a branch droops under a squirrel, cracking seedpods. Rose-colored bougainvillea tumbles over snake plants dividing the campsites. Ornamental oranges glow like globes in a row leading to the campground office and the restaurant.

We arrive on a Saturday morning, knowing that the campground can and does often fill by nightfall. Then it can get noisy, with loud sound systems and the late laughter of partygoers. Mornings, however, are peaceful at La Laguna. At the entrance to the campground, sunlight streams over a darkened hill. It paints a gold patina on an ancient bronze bell hanging from a parota tree. This bell once hung in the church of the original Santa María del Oro. A sign, beside a small open-air tent, announces the future site of a new church. Later on Sunday afternoon, the priest will give a service beside the lake.

Around the lake are rough roads for hikers, horseback riders and mountain bikers to enjoy the vegetation, wildlife and great diversity of birds. The road meanders around the lake, passing October fields of withering corn and wildflowers. On the western shore, a field of blue agave bristles in the strengthening sunlight. In five more years, the huge cores or piñas will reach harvest size for tequila. The town of Tequil is located a half-hour drive to the east towards Guadalajara.

We stroll around the lake, taking two hours to enjoy the sights and sounds. However, by mid-morning, the sun starts burning our snowbird skin. Bill and I head into the shade of the next palapa-roofed restaurant. Bags of oranges bulge from back of a battered pick-up truck. Freshly squeezed orange juice? Yes! The restaurant is open and ready for business. We sit down at a wooden table ten feet from the lakeshore. Bill orders a beer. Ducks, herons and kingfishers dive, shattering the clear lake.

La Laguna de Santa María has always figured actively in local history. Hope MacLean, a Canadian anthropologist camping beside us, at the lake, has studied shamanism in Huichol art over the past fourteen years. She says that the lake was once a major food resource for the Huichol people. However in recent years, the lake has suffered from over fishing. A recent moratorium allowed restocking efforts to gain some success. Imported species of bass and tilapia thrive alongside the native mojarra. In the afternoon I watch a fisherman land a six pound bass from the shores of the campground. He beams at his catch while his wife snaps photos. The man is a member of a fishing club in Guadalajara. He tells us that he has been fishing since 6 a.m. today. He’ll clean and cook this fish but he has released all other fish caught this weekend.

Twenty minutes away, lies the large lake of Agua Milpa. A river tributary was dammed in 1990 in order to generate electricity for the south-east, north-east and north-west states of Sinaloa, Durango, Nayarit and Jalisco. The man-made lake spans a total of sixty-five miles. Bass ranging from 2 to 6 pounds with some caught in the 10+ pound range are caught here. Reaching Agua Milpa is a backcountry adventure among mountains rising up to 6,200 feet.

The region has a long dry season. Our friend, Mario Arcadia grew up in the neighboring village of San José de Mojarras. When he was a boy, he would hike with friends to La Laguna de Santa María. The boys walked for seven miles across the dusty plateau and then climbed down the steep hill. At the lake, they played and swam in the refreshing water. Afterwards, they’d hike back up and trek home, arriving as dirty and dusty as when they left.

I, too, enjoy swimming in the lake. Later in the week, I interview Chris French, the owner and developer of Bungalows Koala. Over discussions about the region’s climate and environmental issues, I ask, “When is the best time of the year to visit La Laguna?”

In a British accent weathered by twenty years in Mexico, Chris answers, “Right now! In late October, the lake is at its lush and loveliest. The vegetation will slowly die until the rains begin next June or July. But La Laguna is always a little cooler than the plateau above …even in the hottest time.”

Chris reports that the lake’s depth of 100-200m provides a deep reservoir for both people and wildlife. The unusual geology of the lake may be responsible for another unusual phenomena. The color of the lake sometimes suddenly changes to a turquoise blue. The color lasts two to three days. The most viable theory may be that earth tremors periodically disturb lime deposits in the lake. Locals also note another link to volcanic activity in this zone. When the volcano, El Fuego de Colima, hundreds of miles away, erupts, fish have died in the lake. It’s no wonder that the founding fathers of Santa María del Oro included the lake on the municipio’s coat of arms.

To protect the lake, a group of stakeholders, including residents, restaurateurs and farmers, commissioned an environmental study in 2000. To prevent the overloading of the ecosystems, jet skis have now been banned. Restaurateurs are being pressured to voluntarily end the discharge of raw sewage into the lake. Boat-owners from the cities or towns still roar in motorboats around the lake. Stakeholders hope that kayaks and rowboats will eventually replace them.

Mondays through Fridays are generally quiet at La Laguna. A retired gringo is cleaning one of the picnic sites after the weekend. We chat about the lake and its long history. Bill Huston and his wife María have driven from the United States to their winter home at La Laguna for the past fifteen years. After answering my questions, Bill adds an invitation, “The Irish ‘madres’ of Santa María del Oro are coming here today for a picnic. You should drop by and meet them.”

Huston says that the madres are nuns who work in the region. Later that afternoon, we join seven nuns and the Hustons by the lake. The nuns wear comfortable slacks. Empty beer bottles and paper plates litter the table. The conversation is lively over a luscious dessert. After the picnic, we arrange to visit the two nuns who work through the Church de La Expiración in the town of Santa María del Oro.

Tuesday morning we drive up the hill to the town, following directions to the nun’s home. Petite Peggy 0’Flaherty answers the door. With a pixy grin, she ushers Bill and I into their two-storied house on the edge of town. The rose garden at the back stretches to a brick wall, overlooking a sea of green sugar cane.

Admiring the garden and the view, I ask, “Are you a gardener?” to Beatrice Donnellan who works with Peggy. “I would love to be. But we are too busy… with the people here. There is so much to do!”

Over tea and imported fruitcake, the nuns tell their story. After leaving Ireland as young women, Peggy and Beatrice Donnellan worked for the Catholic Church in Texas for many years. They arrived in the town of Santa María del Oro in 2000. I’m curious as to how a pair of Irish nuns find living in Mexico, so I inquire to Beatrice,

“How do you like living in Santa María? She exclaims, “I love it! I will stay here until I die.”

“What is the nature of your work here in Santa María?

“Basically we are here to learn local healing practices and share this information with the community.”

“What kind of healing practices might these be?”

“The people share information about the plants they use in the treatment of ailments. They also use healing techniques dating back to their native ancestors. We often visit the isolated ranchos. People here generally have little money. Modern medicines and clinics are an additional expense and a long trip away from home. We work to help people to help themselves. We help them form discussion groups and small self-help groups. We teach alternate healing therapies like massage, acupressure and aromatherapy.”

Bill and I gather more information over the breakfast dishes. By 9 a.m. the nuns are heading out the door to catch a bus to an isolated rancho. Their pick-up truck keeps breaking down and the tires are bald. Funding is slim and the days long for helping the needy. The madres appreciate support of any kind. Before leaving, I promise to write about their work in an article about the gold trail to Santa María del Oro. And you can take that promise to the bank!

How to get There

Santa María del Oro is 50 km S.E of Tepic, 210 km N.E. of Puerto Vallarta and 190 km N.W. of Guadalajara. Take the paved road from the Santa María del Oro turnoff on highway Mex. 15 or from the Santa María del Oro tollbooth on the Guadalajara -Tepic “autopista”. The town is 2 hours via autopista from Guadalajara and 50 minutes from Tepic.

Santa María is also accessible by bus from the second-class terminal in downtown Tepic. Buy a ticket from Transportes Noroeste de Nayarit for a bus that leaves three times a day or ride a long-distance Guadalajara-bound bus in either direction and get off at the tollbooth turn-off to Santa María.

Additional photos Courtesy of Marío Arcadia

This was a most informative article. I’m going to Santa Maria del Oro next week. Really was interested in what the nuns are doing. Are you still in contact with them?

The article was written many years ago, so Wendy is unlikely to see your comment before you go. Please report back after your visit! Have a safe and enjoyable trip.