Mexican History

Our main sources of information on pre-Hispanic religion in Mesoamerica include archaeological monuments and Classic murals, as well as Landa’s Relación and ethnological reports of surviving religious practices and beliefs among the Lacandon Maya of Chiapas and other descendants of the ancient civilizations of Mexico and Guatemala. Of particular importance are the four surviving codices from the Yucatan area (the Dresden, Paris, Madrid, and Grolier). As important as the archaeological evidence is, it is of limited value without some form of written information to support it. With recent advances in the decipherment of the Maya hieroglyphic writing system, we can now “read” most of the hieroglyphic texts. This has opened up the way to a better understanding of the characteristics and functions of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican deities.

Analysis of the signs and symbols of Mesoamerican deities helps us to reconstruct at least the main outlines of pre-Hispanic religion. On the simplest level, a sign simply points to something else. For example, the distinguishing mark of the Maya moon goddess is a reverse “query” sign on her head. But this is also the ideographic glyph for caban (earth), symbolizing her role as an earth goddess. A symbol therefore goes deeper than a sign and operates on more than one level. Wars have been fought over the use of symbols so it is not an insignificant matter. For example, in the Bible the word rock or stone is used in both a figurative or symbolic sense (“Jeshurun… lightly esteemed the Rock of his salvation,” Deut. 32: 15) and in a more literal or metaphorical sense (“…Jesus Christ himself being the chief corner stone,” Eph. 2: 20). However, this subject is fraught with deep pitfalls that we shall avoid in this article. Suffice it to say that in Christian theology, a rock or a stone could lead to a greater understanding of the nature of God or the concept of divinity or it could result in religious controversy over the meaning of the symbol. The correct interpretation of Mesoamerican religious symbolism is even more difficult because of the intense efforts of the early Spanish missionaries to wipe out every vestige of indigenous religion.

Religious symbolism points beyond the immediately recognized object or sign to “something” beyond itself (“…symbols are linguistic or non-linguistic signs that are recognized as pointing beyond themselves to God, the Ultimate, or a transcendent reality,” (A. C. Thiselton, A Concise Encyclopedia of the Philosophy of Religion, pp. 298-99). Theologians and philosophers, such as Jung, Tillich, and Jaspers, argue that symbols transcend the subject-object relationship and immediately integrate the “conscious and unconscious levels of the human mind.” From the theological point of view, the symbol has the innate power to open up the “invisible” and the transcendent to the human imagination. So, too, the symbolism of pre-Hispanic religion enabled the Maya and others to look beyond the immediate world of cause and effect. Their vision of the cosmos may not be the same as ours, but their motives were similar.

We find ourselves in difficulty at the very outset of our investigation. On the one hand, the reference to “imagination” (above) could be (mis)construed as meaning there is nothing beyond the human imagination, no God, no afterlife, and no transcendent “reality.” This poses a problem for the theologian or true believer who is searching for something more than a mere projection of the human imagination. On the other hand, the scientist would be only too happy to argue that there is nothing beyond the function of the brain; that there is no “mind” apart from the automatic firing of the synapses of that physical mass of gray matter we call the brain; and that the theologian and religious believer alike have substituted faith for reason and are therefore entirely deluded. As far as Mesoamerican religion is concerned, both sides would likely dismiss the whole subject of Mesoamerican religion as a prime example of human ignorance and superstition. However, there is always more than one side to any story.

Upon first acquaintance, Mesoamerican religious concepts do seem far remote from what many would regard as “true” religion. A closer look, however, reveals some tantalizing similarities between pre-Hispanic religions and the major Western monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Parallels can also be found among Eastern religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism. For example, the remote Maya god Hunab Ku ( Hun, “One” + ab, “the state of being” + ku, “god”) is the father of Itzamna, principle deity of the Maya pantheon, but he himself is never portrayed or included in everyday affairs (as far as we know). Hunab Ku may possibly have been the Mayan counterpart of the Christian monotheistic God. Likewise, the Mesoamerican concept of Ometeotl (Deity of Duality) was not represented in art but rather symbolized the underlying “transcendental” reality behind the world of cause and effect in which the Aztecs lived at the time of the Conquest. In Classical Hinduism, Brahman is the unchanging “reality” behind the present world, Atman the individual entity (the common translation “soul” is misleading), and Maya the illusion that prevents us from realizing that Brahman and Atman are one and the same. The vast Hindu pantheon of Gods is perhaps the closest parallel to the Maya pantheon of Gods, although some scholars deny the existence of a Maya pantheon as such. One reason is that, in Mesoamerican religion, the number of deities in a “pantheon” can sometimes be reduced to a single deity or concept in which the apparently separate deities are simply manifestations or aspects of the central deity or concept of divinity. This brings us closer to the monotheistic western religions.

In view of the vastness and complexity of the subject, we shall here examine only a sampling of Maya deities, namely Itzamna, Chac, Ixchel, and the Death God from the Dresden Codex (J. E. Thompson, A Commentary on the Dresden Codex, Philadelphia,1972).

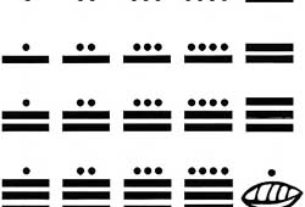

The Dresden Codex was found in Vienna in 1739 and is now in Dresden, Germany (hence the name). It resembles an almanac and is based on astronomical observations. This pre-Conquest ritual-calendrical amatl screen-fold comes from the Lowland Maya region. Contents include, among other things, divinatory almanacs, multiplication tables, astronomical observations, calendrical matters, and representations of deities. The calendrical material suggests a date of around A.D. 1200-1250 and stylistic variations in the day signs indicate that it is a post-Classic copy of a Classic period edition.

Itzamna (Iguana House), sky god and principal Maya deity, is graphically depicted in Classic Maya art. In post-Classical codices he appears 103 times in various forms, such as a celestial monster, a lizard, or an old man with sunken cheeks and toothless jaws. As a creator god and culture hero, he invented writing and books. In the Dresden Codex (pp. 4-5), he is symbolized in one of his aspects as a celestial earth monster with the head of God D (the earth form of Itzamna) in its open jaws. As sender of rain, he is depicted in colourful detail with torrents of water pouring out of his mouth (Dresden 74). The late Maya scholar J. E. Thompson speculated that there were four Izamnas or aspects of Itzamna supporting the four corners of the heavens. As supporting evidence he refers to a section in the Mixtec-Aztec Borgia Codex, which clearly shows four plumed serpents encircling the four cardinal points. The relationship between these plumed serpents and the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl is a matter for further speculation and investigation.

The rain god Chac appears even more often than Itzamna (218 times in three codices). He is symbolized by a long nose, two projecting fangs, and a T-shaped glyph. This deity, which represents the four gods of the cardinal points, is associated with different colours – red for the East, white for the North, black for the West, and yellow for the South. The multiple aspects of these deities may be compared with the Christian concept of the Trinity. In the Dresden Codex, the Chacs are depicted at the four world directions and at the center of the earth (Almanac 53, pp. 29a-30a). The Chacs are of course the Maya counterpart of Tlaloc, the rain god(s) responsible for the recent deluges in the Lake Chapala area.

The moon goddess Ixchel was the patroness of medicine, diseases, childbirth, and divination. A large section of the Dresden Codex (pp. 16-23) is dedicated to the activities of this important fertility goddess, who is both an elderly and unfriendly water goddess and a young woman. In one section, an aspect of the goddess is shown as a full figure seated and carrying a burden ( Koch) on her back. A block of four glyphs above her head tells us that she is carrying a screech owl (evil) symbolizing the ills that are inflicted upon the human race. An interpretation might go like this: “The a coo akab (mad one of the night, i.e. the screech owl) above the 13th heaven is perched upon the shoulders of Colel (another name for Ixchel). It is her evil (or the evil burden she bears).” This is a typical Maya pun on the word koch, which can mean “bear on the shoulders” or “disease” (as divine punishment).

The fourth most frequently represented deity is the Death God, easily recognizable from the sleigh-bell ornaments on his arms and legs or attached to a collar. With a skull for head, bare ribs, spine showing, body bloated, and skin marked with black spots of decomposition, he well symbolizes the Maya dread and loathing of death. Appropriately, he was the patron god of the day Cimi (Death) and as in Dante’s Divine Comedy, he presided over the ninth and lowest of the levels of Hell. Not surprisingly, he was also associated with god of war and human sacrifice.

These are just a few of the Maya deities found in the hieroglyphic codices. At first this parade of fantastic figures and elaborate glyphic symbols marching throughout the Dresden and other codices seems quite alien to our way of thinking. But when we compare Maya religion with other religions around the world, we find people throughout the course of human history have asked similar questions about the purpose of human existence and come up with very different answers. It is perhaps debatable if we have found any better solutions than did the ancient Maya.