Guanajuato is, and has been for a long time, a centre of culture and education. In one way or another, it has always been prosperous, either through the richness of its farmland or its mines. There was the money to support cultural activities and the desire on the part of the rich mining families and hacendados, I imagine, to live a life that included music and theater and the appurtenances of the cultivated middle and upper class.

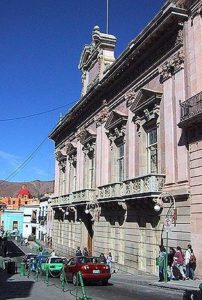

In 1989, the city was declared a World Heritage Zone, partly due to decades of effort by Victor Manuel Villegas Monroy, a world-renowned architect. His work led to restoration of a substantial amount of the city’s colonial architecture, as well as preservation of the elaborate and beautiful buildings constructed during the Porfiriato (the government of Porfirio Díaz, 1877-1911). The Teatro Juárez is an example of this.

So, for a city that is small by US standards (73,000 inhabitants), it is rich in exceptional performance venues for music, dance, and theater. There is an abundance of museum and exhibit space, as well as in general everyday public living spaces. It seems to me that almost every other street has its small plazuela or at least a little place with a nice bench where you can sit and take a breather. This is partly the European heritage which is so evident in many parts of Mexico, but also due to the fact that many private living quarters, except for those of the fairly rich, are what most middle class US citizens would deem unacceptably small.

I personally feel enormously refreshed by the lack of “stuff,” (to use George Carlin’s memorable phrase), which I have increasingly felt to be an encumbrance rather than any reflection of richness. Therefore, I personally enjoy the almost ubiquitous, richness of the public spaces.

Each year, for the past 28 years, The Festival International Cervantino (FIC) takes full advantage of Guanajuato’s wealth of performance venues. I list them in the order in which they appear in the Cervantino’s master calendar brochure (year 1999): The Teatro Juárez, The Teatro Principal, the Teatro Cervantes, the Patio of the Faculty of Industrial Relations, the State Auditorium, the Plaza San Roque, the Esplanade of the Alhondiga, the Teatro de Minas (Mines), the Templo (Church) in Valenciana, the Ex-Hacienda of San Gabriel de Barrera. As if this were not enough, there are seven museum spaces, which featured various exhibitions, ranging from photography to a couple of installations (one with music, one without). Each area is very individual and clearly the organizers of the FIC, of which Sergio Vela is the Director, take conscientiously into account which performers and artists will work best in which space.

The artistic wealth of Cervantino is hard to convey without just reprinting the brochure in its entirety. Three operas (Carlos Chávez’ The Visitors, a multimedia Canadian production of Orfeo, and Robert Wilson’s Persephone); four or five dance companies including the renowned Ballet Folclórico of Amalia Hernández of México and the Ballets Folclóricos of Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic, the Anhui Acrobats of China; the Baroque Orchestras of Montréal and Freiburg, various early-music groups, the Quinteto Rodolfo Mederos from Argentina (he played with Piazzolla, as everyone knows one of my heroes); excellent soloists too numerous to mention, the Arditti Quartet, the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, the Mexico City Wind Quintet, conductor Kurt Pahlen, the Harp Consort, on and on …. does this give you an idea?

In 1999, I went to ten concerts and a play. The highest price for a ticket, in the Teatro Juárez on a Saturday night, was 200 pesos, which in US dollars comes to about $22. I didn’t pay anywhere near that much, because so many events are either free or available at times when the ticket prices are substantially lower.

I started the Festival off with a bang, because a friend of mine in local government got me a ticket for the special guest section of the Alhondiga for the Inaugural night concert, which was by the Afro-Cuban Allstars. The Alhondiga is Guanajuato’s equivalent of a stadium. By US standards, it is about one-tenth the size of an average arena. It is a relatively old building, which dates from the mid 1700’s and, as its name “Esplanade” implies, has a bunch of steps flowing down to a flat area in front of the stage, erected there for special events. ALL the Cervantino events at the Alhondiga are free. This means for a popular event, if you go as “part of the people,” you must arrive anywhere between noon and 4 p.m. to reserve your choice spot on the steps for the evening’s 8 p.m. show.

I went with friends (some fellow-Fulbrighters who came up from México City) to the Clausura or last concert, which was Cristina Hoyos and her flamenco group, and we went as part of the people. For the Afro-Cubans, I got to go as one of the special people and so could arrive ten minutes before 8 p.m. without fear of not having a seat. Although the location was fractionally better, it wasn’t as much pure FUN as getting there really early and hanging out and eating and joking and having a “one of the people” concert experience. The sightlines are so good there that there really are no bad seats.

The Afro-Cubans were wonderful. For those of you who know the group or have seen the movie “Buena Vista Social Club”, or own one of their albums, you probably know that both Rubén González and Ibrahim Ferrer were there, boasting a combined age of at least 150 years. Both performed, with a charm, energy, and heart, which was bewitching and energizing. They reminded me of players like Horzsowski and Rubenstein for the astounding and inspiring love and energy that just flowed out of them with their music. Age had no significance except for the accumulation of more wisdom and imagination in their playing, and it is the same with Ferrer and González.

This is popular music, and in the best sense of the word, that is “music of the people.” Like the blues and flamenco, it tells of passion, flirtation, heartache, tough times, and the native cheerfulness and optimism, which the human imagination summons to get through all these things. Many of the tunes the Afro-Cubans performed were not recent hits, they were old songs (some decades old), like María Teresa Vera’s Veinte A ños, songs with which the musicians and many other people had grown up and with which they therefore felt a special affectionate relationship, like with their mothers. Gary Snyder says somewhere in The Practice of the Wild, in an essay about visiting a remote Eskimo settlement’s library, “books are our grandparents”. Songs, in this sense, are our mothers, maybe.

One of the hallmarks of this music is the scope it gives to improvisation, not just by the instrumentalists, but also by the singers, with flamboyant vocal adornment and, in the words, on subjects, which are generally topical like politics or the venue of the show. During these episodes the band just riffs and plays ostinato patterns while the singers compete back and forth, like old-time jazz players “cutting.”

I find the rhythms and melodies of this music irresistible and was on my feet halfway through the show, dancing together with a daring few (young) others in the special people section. The regular folks up on the steps didn’t sit down during the whole show and were dancing almost from the first note of the first tune. This is another reason the special people section is not as much fun! My greatest teacher, Theodore Lettvin, once said, “If it’s not a song or a dance, it’s not worth playing.” Could we say too that one measure of great music, and great music making, is that it makes us want to sing or dance, to lament or kick up our heels?

A few days later I went to hear the Coro Orfeón Santiago, also from Cuba, in the Templo de Valenciana. This is a cappella group of eighteen singers (5 sopranos, 4 contraltos, 5 tenors, and 4 basses), directed by Electo Silva, who also composes and arranges. How do I describe what happened in that beautiful church, high in the sierra above Guanajuato, not a tremendously large space horizontally but high, high, tall, as if mimicking the hills, striving towards the heavens? They entered singing an anonymous melody from 17th-century Perú, with text in Quechua (an indigenous language), walking deliberately, and finished on the small wooden stage. Haunting, simple, faultless intonation, the voices rising through the silent breathing air of that space, upwards with the rising ceiling and with the mountains outside, toward the brilliant sky. It was as though their breath, singing, was keeping us all alive.

For two solid hours they sang, all from memory, with no intermission. The voices were effortless. I wish we could hear this singing in the States. There was no PUSH, no sense of effort. Never, even in the numerous emotional moments during that concert, did I have the sense that anyone was working for a note, or indeed trying for anything. It was as though the voices came not from the singers but from the earth, rising through the soles of their shoes and coming pure and unfiltered through the vessel that was the body, straight to our souls by way of their mouths and our ears. Electo Silva, slender and clearly old though ageless, and who bears a slight resemblance to Yoda in his beneficent smile, gave galvanic upbeats and then often stopped conducting, just standing to one side with that beatific smile on his face, just LISTENING.

Repertoire — after the anonymous song from 17th-century Perú came two songs of Juan Vásquez from 16th-century Spain, a song of José Cascante from Colombia, also 17th-century, and Randall Thompson’s Alleluia. Then two poems of Neruda set by Blas Galindo, the long-lived and prolific Mexican composer of our own century, a song of Ariel Ramírez which talks about Argentinean poet Alfonsina Storni (who committed suicide by drowning), Alfonsina y el Mar, the solo contralto part so achingly beautiful that everyone in the place could barely breathe; a song of José Barros, Creole French folksongs from Haiti and Guadeloupe, and two songs in French by Jacques Brel.

The second half of the program was music of Cuba. Three sections of a Misa caribeña (Caribbean Mass) of conductor Electo Silva; songs of Sindo Garay, Miguel Matamoros, Jaime Prats, Alejandro Rodríguez, and Ignacio Piñeiro; two settings of Nicolás Guillén, the Cuban poet who often wrote in a creole-influenced Spanish, by Electo Silva; and Silva’s Variations on La Guantanamera with the famous text of Cuban liberator José Martí. And lest I forget, three songs in homage to María Teresa Vera, a Cuban singer and songwriter of this century: her own Veinte Años (Twenty Years), and songs by Rafael Gómez and Óscar Hernández, all arranged by Electo Silva.

Thus the music of the Coro Orfeón Santiago spanned, in its styles, everything from the purest baroque to spirited improvisations by all the singers in the same vein and in the same tradition as the Afro-Cubans, without ever losing its sense of cohesion, commitment, and just awesome craft and musicality. Among the many moving moments here, surely one of the most moving was to hear Veinte Años … which I had heard a few days before sung by the Afro-Cubans.

There was no division here between “popular” and “classical” music. No rupture. No loss of continuity. The elements of the “popular” flow effortlessly and openly into the output of “classical” or “art music” composers without the painful questioning about whether this is “appropriate” which I often feel afflicts this process in other places

And there was no division between “old” and “new”, not even a thought of it. That music from 17th-century Spain is as much a living part of what they are doing as is Mar ía Teresa Vera’s Veinte Años, as much a mother to their music-making, held in as much affection. There is no argument about whether it is “appropriate” to sing a “pop” song in a concert of “classical” music. Those labels are irrelevant, as they should be. There is a value assigned to the past, to heritage, to history, to the FAMILY of music, which is INclusive, not EXclusive, where what matters is the skill you work to bring to your art and the heart and imagination with which you practice it, the voice you give to the music.

Of course they were called back for encores, and they sang several. By the time they were clearly on the last, I was in tears, and I was not alone. They walked off singing as they had arrived, and every single one of them was singing through tears, and the audience was in that state of catharsis that comes only after very great music making.

I’ll make my only political observation: that anyone who thinks that frontiers and embargos and fences can stop the flow of music between peoples, that essential water of music, is just plain crazy. We need to hear this music in the US and it makes me loca to think that every single one of you can’t because of …