I spent a long time studying the eyes of the Olmecs, the lips, noses and facial expressions of the Toltecs and those from Colima. It was the work of all who went before me that enabled me to do what I do today.

Over a generation ago, Martín’s father, twenty-five year old Sixto Ibarra was digging for sweet potatoes on a hillside near his village of San Juan Evangelista. He fell forward as his trowel encountered air instead of soil. Burrowing deeper, Sixto uncovered an ancient, pre-Hispanic burial ground. The tomb was filled with marvelous, mysterious clay figures.

Sixto had been a professional musician, as were his father and brothers. Musicians’ not being in constant demand, the young man had time to marvel over the clay images he had discovered. The animal figurines that could also be played as whistles especially intrigued him, and he thought if men could create such things centuries ago, maybe I can also do the same today.

There was no tradition of pottery in Sixto’s village, at least in recent memory, but he decided to dig up some local clay and try his hand at reproducing the smaller figures. Before long he was walking the streets of San Juan and nearby villages with a basket on his back, selling his clay animal whistles from door to door. These were especially popular with the children, who had few other toys or amusements.

Don Sixto never returned to music, choosing to continue to work in clay: experimenting, perfecting his craft, traveling, eventually exhibiting in museums, and teaching his sons, nephews and any others eager to learn from him. Even though Maestro Don Sixto Ibarra died in April of 2001, I could sense his constant, almost palpable presence during the hours I recently spent with his son. Martín Ibarra Morales never forgets for a minute where the story began.

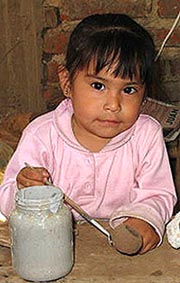

“Now I have four children of my own and the youngest, Paula Milagros is only two years old. She already enjoys watching when I’m painting or burnishing a piece. If I hand her a brush she begins to paint and says, ‘ Estoy trabajando‘ ” (I’m working).

Martín’s daughter

is eager to begin

It isn’t easy to find Martín. Wending one’s way south of Guadalajara toward the town of Chapala, turn right toward Lake Cajititlan and, after a few more turns, one reaches the town of San Juan Evangelista, and the journey is almost over. By simply asking for “Martín,” you will be led inevitably to his house. There’s no house number to jot down for future reference, nor is there a sign above his door. The simple adobe home is located on a corner, across the street from the large village church courtyard.

Slim, wavy-haired and youthful looking, Martín first welcomed me last January into the humble home and workspace that he shares with his wife, mother and four children as well as other potters during the workday. I had already read about him in local newspapers as well as such prestigious magazines as El Antiquario. Most recently I had seen impressive examples of his work at the October Maestros del Arte exhibition in Ajijic.

Aware that Martín is an acknowledged master of his craft, I was somewhat surprised at how humbly he lives – dirt floors, small rooms, and a miniscule display area are open to visitors. It didn’t take long to become so engrossed by Martín’s stories and enchanted by his art that I became oblivious to anything else, and felt totally at home.

After he had described that first childhood success with the ocarina, I wondered whether Martín had made any major mistakes during his subsequent apprentice years. He smiled, leaning over from his small stool, and began drawing something for me on the dirt floor.

“My father asked me if I could mold a large figure of a pre-Hispanic cargador (carrier), one with many big pots on his back.” Martín scratched a diagonal line in the dirt to illustrate where the center of gravity would have to be located for such a sculpture to succeed.

“Now I was older and feeling quite sure of myself. I didn’t hesitate for a second to accept my father’s challenge. I worked so long on that sculpture,” Martín continues, “but his legs were too straight and didn’t contain enough clay. When I took him out of the kiln and stood him up, he immediately fell over on his back and shattered into many pieces.”

It was obvious from his laughter that Martín considered this a valuable learning experience. In fact he assured me that he immediately began making a second cargador, and that one stood, perfectly balanced.

As I came to know Martín better over the course of two visits, it became clear that where and how he lives is a matter of very conscious choice. Many times over the years, companies, exporters and enthusiastic collectors have made him seductive offers.

Martín says with a smile, “One even promised me, ‘If you will work for me exclusively, I will provide you with a large house in one of the best neighborhoods in the city, the best schools for your children, even a car.'”

Becoming more serious, Martín leans towards me and continues, “I asked him, ‘Who will pay for the taxes and repairs on my fine house? Who will pay for the schools, the uniforms and the books for my children? Who will purchase the gas and pay for the repairs on my car? No thank you, I shall remain quite happily here in my village of San Juan.'”

On my first visit to the Ibarra home and studio, Martín was completing a small figure of The Virgin of Talpa. I had seen a larger version in a private Ajijic home, but now became absorbed and fascinated by the lovingly minute details he employed to complete this smaller commission. Tiny holes had been left in the figure for future placement of the hands, scepter, the baby Jesus, and the cross topping Maria’s crown, and each of these pieces had been fired separately in the kiln.

Martín, who refers to himself as a detallista, invented this system. He is not only fascinated by detail but also is constantly asking himself “why?” and “how could this be improved?” In this particular case, he has solved the practical detail of preventing breakage – in the kiln or elsewhere – of the most delicate portions of his creations. In case they should be damaged, they are much more easy to replace.

Once, a few years ago, some of the city fathers decided to try promoting village ceramics. They even produced a map pointing out the individual locations,”Martín said. ” Fulano de Tal (Mr. So and So) was listed as an expert in virgenes, another was promoted for his spheres.”

Then they came to me. “And how shall we list you Martín?” they asked.

“I told them, ‘Please don’t limit me or give me any labels. That way my imagination and creativity can be free and continue to grow.'”

In recent years, though his whistles, plates, esferas, (spheres) and large amphorae are much sought after, Martín has become best known for his virgenes. Not long ago a virgin was even commissioned as a present for King Carlos of Spain. I asked Martín how he came to make virgins, considering he had begun, as his father’s student, with pre-Hispanic figures.

He told me, “A client came with a crude drawing of a virgin. It was just a triangle, with no decoration. If you looked at it from the side it resembled, more than anything else, a brick.”

Martín wasn’t happy with this commission, but he agreed to make just one. When the client returned, asking for three more of the same, Martín replied, “Alright, but only on one condition. I will make them the way I want to. If you aren’t pleased with the results, you don’t have to take them.”

The client accepted the new, heavily decorated virgins and soon returned, all smiles; his clients had been wowed. Thus began the now famous Martín Ibarra virgins, with their sweet, delicate faces, and intricately designed and decorated gowns and cloaks.

Each of Martín Ibarra’s pieces is molded by hand, including the spheres. He explained that he starts out with a ball of clay for the latter, and begins working it like a tortilla. For anyone who has seen the finished engraved, painted and burnished product, that description seems incredible. Martín added that a plaster of Paris mold might be permissible only for someone, a child perhaps, who is just beginning to learn the art of molding a sphere.

After being formed in the desired shape, a clay figure is destined to pass through many additional stages. First comes the design. This may be either grafiado, a technique already used by the ancients, with complicated graphic designs scratched into the still damp clay. Even more impressive is the technique of alto relieve, (high relief) where the roses or curlicues on a virgin’s robe are formed then applied on top of the figure, damp to damp. Next all pieces are carefully painted, burnished and finally placed in the wood-burning kiln.

I asked Martín, considering how much loving effort goes into each piece, what percentage he loses to the unpredictable vagaries of the kiln. “I hardly ever lose anything.” he replied. “The simple trick is just to pay attention,” he added, proving himself once again to be the master of detail from beginning to end.

I wondered whether this artist who is always asking himself “how” and “why,” has any creative ideas he hasn’t yet brought to life.

“Yes,” he said, “I dream of a large globe, engraved all around with the entire Aztec calendar and supported on the back of two jaguars. If I only had the time.”

Sometimes Martín interrupts his very concentrated work on the figure of a commissioned virgin and relaxes by “playing” with something else. On my first visit he picked up a small amount of clay and gave it to me to touch – so cool, smooth, and very sensual. I returned the clay to him, and the figure of a small but ferocious, crouching jaguar began appearing before my delighted gaze. Having been present at his creation, I asked to have the jaguar when it was completed. I also ordered a small Virgin of Talpa for my very own.

The day I first met Martín at the Maestros del Arte fair, I was in search of clay bird whistles. A friend had told me that, when filled with water, the whistles twittered and trilled like real birds. When I found him, Martín was sold out of the popular item. In January, I ordered a few bird whistles as well, though I’d yet to see one.

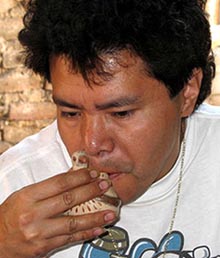

During our February interview he played one of the bird whistles; it sounded as lovely as promised. Together we also painted and burnished the little jaguar he had begun in January. Purposely Martín had waited for my return so that I could participate in all the stages. The jaguar was fired on the simplest of kilns, similar to one the Toltecs might have used. Martín arranged a few pieces of dried cattle dung, placed my jaguar in half a tin can in the middle, lit the fire, and 1/2 an hour later he was complete.

Gazing at the box now carefully packed with my Ibarra treasures; the virgin, the whistles and not least my very personal jaguar, I asked one final question. “What would you most like the readers of my article to know?”

The master of detail replied, “I was criticized at one time for making pre-Hispanic reproductions instead of my own pieces. What those people didn’t understand was that I spent a long time studying the eyes of the Olmecs, the lips, noses and facial expressions of the Toltecs and those from Colima. It was the work of all who went before me that enabled me to do what I do today.”

“I also want people to know the following: no matter how many copies exist today, made from molds, made by people claiming to have studied with my father, Sixto, it was here in this room; here and nowhere else is where it all began.”

“My father always said the only way to have a happy life is to do what you enjoy. As for death, it is bonito. It is the only thing we can expect for sure. If one dies at peace and still working, it is beautiful.”

Update (see comments) – Martín Ibarra Morales died in 2021. QEPD.

I went to his house a few weeks ago, and his wife told me that he died last year. A great artist was lost. I have enjoyed filling my house with his work for over decade, and I’ll remember him fondly.

Thanks for the update. Sorry to hear about his passing, but pleased that you have so many happy memories of him.