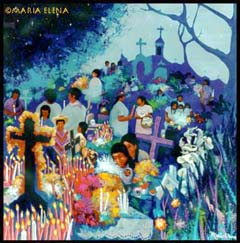

In Cuernavaca, on the top of a hilly barranca, parallel to Calle Morelos on its way out of town, lies a beautiful new cemetery. A Panteon, already lush with bougainvillea and shrubbery lovingly planted on graves and crypts. Trees had been left standing, framing the natural landscaping and parading like sentinels for the dead on the upper levels of the barranca. Flowers were everywhere, their color and fragrance lightening the day of the those bustling south, on the way to Acapulco.

An enterprising governor had liberated this land from the “ejido” qualification, that of belonging to the people. He and some associates had constructed a fine building, built a series of roads and paths, drainage, a small series of streetlights, and lo, a new cemetery. His constituents sighed and thought, Well, it was better than a fraccionamiento [a housing development], anyway.

The people of Cuernavaca went to the grand opening and were quite impressed, myself included. The old cemetery had been a disgrace for decades, old mouldy stonework, cracked and tipped over from earthquakes. No grass, just dead and rotten flowers from offerings, and a sea of mud during the rainy season. It lay under massive eucalyptus trees, its very air contaminated with the detritus of the centuries, malarial mosquitos, and wall-to-wall fleas. We who had our dead there had buried them fast and left with bugs whining after us.

So the people of Cuernavaca began burying their newly dead at the new cemetery. Indeed, some of us even went so far as to transfer our dead from the appalling old cemetery. We planted bougainvillea and lilies and landscape shrubs and felt rather virtuous. Relieved, certainly that we had gotten our dead out of “That Place.”

As my sons and I were shopping for new headstones, we were told that it was not permitted to take orders for installation in the new cemetery. It seems that, the governor having left office, the new governor and everyone else with any authority was investigating the old governor, and his business dealings. This was just when the politicians were starting to be caught in their manoeuvering, something unheard of previously, when people were proud of politicians who made it big. It was a new era, however, and the people were tired of their suffering and wanted to lay a little of it on their leaders, who had outdone themselves in misdeeds during the last few administrations.

So everything stopped at the new cemetery. Those who had already put in monuments, indeed, entire stone houses, worried. There was talk of the ejidatarios becoming administrators of the cemetery. It was understood that the land would be given back to them, as it had been taken unlawfully. There had been no uproar when the land had been eased away from the ejidatarios, the People of Mexico, but now everyone was ashamed of their politicos and wanted to make amends. Everyone waited to see what would happen to their dead, praying that they could stay in the beautiful new panteon, and that the ejidatarios would prove that they could administrate their own property. My sons and I decided that Grandma, Michael and Patricio would not mind having a little wait for their gravestones.

A few years later, the ejidatarios had won their battle, the ex- governor was in disgrace, and the business of laying the dead to rest was flourishing again on top of the barrancas. The ejidatarios, mostly jardineros and such, had never stopped caring for their property, and at the reopening, all Cuernavaca was pleased, including me. I opened negotiations for three gravestones once again before departing for a show in Costa Rica, leaving a check and the panteon papers with my partner, Juan, who would attend to everything.

Three months later, upon my return, I triumphantly set out to take a photo of the monumentos. Juan had assured me that everything was in place perfectly, but someone had swiped the purple Bougainvillea that were planted at the heads of the graves. So I arrived with shovel, clippers, watering can, camera, new purple Bougainvillea clippings from our house, whatever. And I was lost. I knew I was in the right aisle because a friend, Carlos Quintero, was buried right across from Michael; the well-known painter Guerrerro Galvan was buried in front of Grandma, and just down the aisle was my favorite taxi-driver’s entire ancestry, smothered in lily pots. Where were Mother, Mike and Patricio?

I put down my cargo and looked around. There seemed to be three suspiciously familiar bougainvillea plants to my left. Unclipped for several years, they were larger than I remembered, indeed huge, but they were unmistakably my own personally invented [well, God and I] bougainvillea purple. I fished in the Panteon papers for the map. Definitely, here I am. I saw the weathered remains of the wooden cross that Bob had fashioned temporarily for Michael, almost lost in the purple flowers.

I knew Juan would never have neglected his charge; he was and is the most responsible person I know, so I started walking around, having a look. About ten minutes later, I found my gravestones gracing three other persons’ graves, on the back of the next aisle over. Mother would have approved of them, they were quietly elegant and understated as to information, deeply grooved. I trotted up to Administracion, papers in hand, demanding the return of my gravestones. ” Como lo siento, Senora, pero no es la culpa nuestra…the installers did it and they work for the stonecutters.”

I called Juan. “Didn’t you go with them when they put them down?”

” Pues, no…tu sabes, fue un sabado…” Saturdays Juan sold his paintings in San Angel.

Mortified, Juan didn’t believe it until he saw it. He tried to argue with Administracion but got nowhere. The worst was yet to come. Administracion now regarded those gravestones as the property of the gravesites below them. Upon looking in their massive book to see who the lucky owners actually were, they found that nobody was buried there at all yet. So what happens now? Well, in that case, the gravestones belong to Administracion. Juan hung his head.

Well. I talked it over with my sons. None of us felt up to a skirmish with the mighty Ejidatarios, now spelled by the press with a respected capital E, who had already battled the governor and all of PRI for years, and won. I didn’t have the money for another set of gravestones and I was sure Mom, Mike and even Patricio would feel that those magnificent Bougainvillea were enough. After all, they were somewhere else anyway. So we left it like that. Somewhere in the beautiful new cemetery there are three white marble understated gravestones, SUE 1902-1974; MICHAEL 1956 – 1973, PATRICIO 1964, in the warm sunshine of Cuernavaca, probably still with nobody buried under them. White marble is hard to fiddle with. Even Michaelangelo himself would have had trouble changing the lettering.

Article and Images by Maria Elena

Copyright © 2000 by Maria Elena.

All Rights Reserved Worldwide.