Excerpts from the Prologue by Carlos Fuentes :

To see Mexico from the air is to look upon the face of creation. Our everyday, earthbound vision takes flight and is transformed into a vision of the elements. This book is a portrait of water and fire, of wind and earthquake, of the moon and the sun.

For it is we – you and I – who see and touch and smell and taste and feel today, even as we witness the perpetual rebirth of the land here and now. We are the witnesses to creation, because of the mountains that watch us and in spite of their warning: “we will endure, you will not.” Our response to this warning can be as sinful as pride, but also as virtuous as charity. We take the earth in our hands and recreate it in our own image.

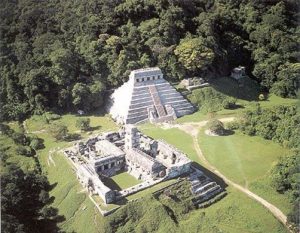

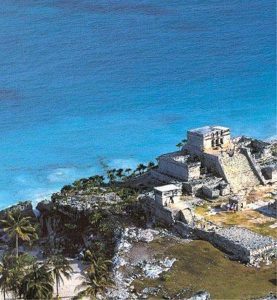

Geometry, Einstein said, is not inherent in nature. Our mind imposes it on reality. In these photographs, man’s geometric imagination is marvelously observed, from the air, in the incomparable clash of jungle and architecture in Palenque and Yaxchilan. It is at these sites that the primeval struggle between nature and civilization seems to have taken place, indeed it is still going on. Nature embraces architecture, but the human creation suffers because, while desiring to give itself up to nature’s almost maternal tenderness, it also fears being suffocated by it. And, as human beings, we also fear that we will be expelled from that great, moist womb that nurtures and protects us and cast out into the shelterless world.

The great art of ancient Mexico is born from this tension between nature and civilization, between fear of enclosure and fear of exposure. The splendor of the great acropolis at Monte Alban and the sacred spaces of Teotihuacan are the triumph of but an instant of human domination, yet also human equilibrium, with nature. In these places, man has met time and made the shapes of time his own.

From the air, Puebla, Oaxaca and Morelia display their checkered innovations, as well as their mestizo ambiguity, while Taxco, Zacatecas and Guanajuato yield to the serpentine cityscapes called for in the mining districts. Like the gold-seekers themselves, these cities scramble up the mountainsides, tumble down the slopes and sniff out their precious metals. When they find them, they adorn their altars with them, pave the streets with silver when their daughters get married, or lose their gold forever in a bet, on a whim, at a fiesta.

There is in this book a splendid photograph of the Barranca del Cobre, the Copper Gorge, in Chihuahua. Like the other canyons of the Americas, especially the most glorious of them all, the Grand Canyon, this great Mexican abyss bears witness to the two extremes of creation: birth and death. It this is a picture of the first day of creation, it is also a portrait of the last. The drama of these places does not end, nevertheless, in an affirmation of the beginning and end of the earth. Their greatest effect lies in the way such places define our frame of reference step by step as our vision moves through space. In Arizona or Chihuahua, the reality of these natural wonders is actually determined by our movements. A step to the right or left and the great stone abyss that we see changes so fundamentally that we never look on the same gorge twice. The movement of our body, our change in point of view, transforms what on the surface seemed an unalterable monument of nature.

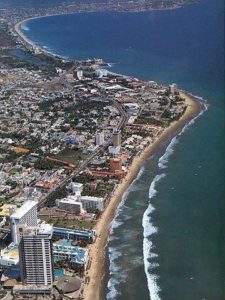

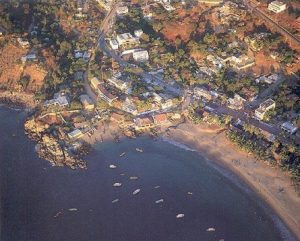

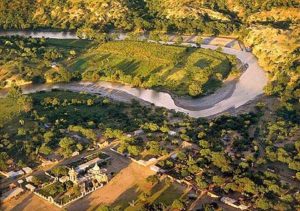

This volume reminds me that looking through it is like penetrating the wealth of Mexico and discovering at one and the same time its permanence and its transience. For one moment, nothing changes and all the elements unite harmoniously. White birds resting in the waters of a power dam rob it of its engineered coldness. Cattle and wheat fields, derricks, hotels, haciendas, modern cities and beach resorts – these are all names for abundance. But do they express harmony as well? Perhaps real serenity is far more modest and intimate. I find it in an aerial view of Tlacotalpan with its peculiar knack for harmonizing gaiety and reserve. Here is a livable sensuality, the very definition of life in Veracruz.

Abundance also means the flight of the flamingos coming to feed, the pink blur of the birds on an orange sea, the silhouette of the jungles green shadows. The shock of Mexican colors and the mutable hues of nature come together in a recently repainted village church or in the haven of a Oaxaca hamlet. This is perfection, the harmony we long for, the peace of the elements.

What we see in this book is a portrait of the cycles of creation, a portrait of the skies and the succession of Mexico’s suns over Mexico, the authority that the country and its people derive from a relationship with the elements that gives no quarter. This book allows us to assimilate the portrait of the Mexicans with the portrait of creation.

That is why human victories are greater in Mexico. No matter how harsh our reality may be, we do not deny any facet of creation, we do not deny any reality. We try, instead, to integrate all aspects of the cosmos into our art, our way of seeing, our sense of taste, our dreams, our music, our language.

From the roof of Mexico, one can better appreciate this way of being. We are like Calderwood’s picture of that sculpture of a god by Rivera which can only be truly seen at a distance, from on high.

This is a portrait of a creation that never rests, because its work is not yet complete.

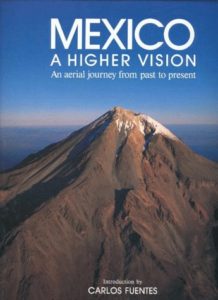

Excerpts from Carlos Fuentes’ Prologue to:

MEXICO: A HIGHER VISION, An aerial journey from past to present

Photography by Michael Calderwood / Introduction by Carlos Fuentes

Alti Publishing, 1996 / Available from Amazon Books: Hardcover

Excerpts and photographs Reproduced with permission of the Publisher