From the book “CASA MEXICANA” ©1989 Tim Street-Porter, published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang, New York.

Reproduced by special permission of the publisher and author.

Photographs by Tim Street-Porter © Barragan Foundation, Switzerland / ProLitteris, Zurich, Switzerland

Luis Barragán was born in Guadalajara in 1902 of a prosperous, aristocratic family, and grew up on a large ranch near the remote village of Mazamitla in Jalisco, a region known for its beautiful vernacular architecture.

Although trained as an engineer, Barragán discovered he had a closer affinity with architecture. He did not receive formal training and never officially became an architect (which did not prevent him from receiving the Pritzker Award, architecture’s “Nobel Prize,” in 1980). His architectural education came from engineering school (which was sufficient to enable him to build houses), from other architects, and from practical experience. He felt later that his lack of academic training in architecture was probably a blessing — freeing him from the rigid approach of many of his peers and allowing him to arrive at instinctive solutions to design problems.

In his early 1920s Barragán spent a formative two years in Europe. In France he encountered the writings of Ferdinand Bac, a French landscape architect, illustrator, and intellectual. Bac’s illustrated books on the art of landscaping – Le CoIombier and the Enchanted Gardens – suggested that gardens should be enchanted places for meditation, with the capacity to “bewitch” the onlooker.

These ideas were a huge influence on Barragán’s future landscaping career, especially since he was able to relate the Mediterranean environment portrayed in Bac’s illustrations to his native Guadalajara with its similar climate. When Barragán finally met Bac and discussed architecture with him, Bac showed him “with the force of a revelation a new and deeper understanding of the basic elements of building beams, roof-tiles, arches, and how natural elements such as rocks and stones, the water, and the horizon played a role in design.

Returning to Guadalajara, Barragán resumed a friendship with two architects of his generation, Rafael Urzua and Ignacio Díaz Morales. They were also beginning to build houses with a Moroccan influence similar to those of Barragán. Together they studied the Bac books, and Barragán began to design patios which would “bewitch” the user, and to pursue his search for an “emotional architecture.”

In the late 1930s Barragán moved to Mexico City. He designed a series of buildings in the International Style, which by then had become popular in Mexico (more so than in almost any other country).

It was in the 1940s that Barragán began to discover the more personal style by which his later mature work is so easily recognized. From 1943 to 1950 he was occupied with the gardens of Pedregal, a landscaping project in a wilderness area of black volcanic outcrops near San Angel in the southern part of Mexico City. His intention was to create an area of select housing, disturbing as little as possible the unusual, almost lunar landscape. He acted as developer and architect, designing several houses for the Pedregal and laying out streets, pools, pathways, and fountains – always in a manner that deferred to the natural rock formations. Walls of lava-rock divided individual lots; natural vegetation, augmented by cacti and pepper-trees, was preserved.

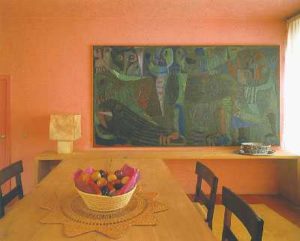

Soon after Barragán moved to Mexico City he had met another Guadalajaran, Chucho Reyes. Reyes – an artist, antiquarian, and taste-maker – was a passionate advocate of the indigenous culture of Mexico. He had been influential in the transition from French to Mexican influences in interior decoration that occurred during the 1930s and 1940s. A strong affinity developed between the two men, and Reyes became a major influence in Barragán’s creative growth.

During the period of his work on the Pedregal, Barragán employed Reyes (paying him by the day) as a consultant. In addition to helping with everyday design problems, Reyes was a catalyst in Barragán’s radical metamorphosis of style. Barragán’s generic, International-Style apartment buildings and Moroccan-influenced houses of the 1930s gave way to the highly abstract and personal work of his mature period, beginning in the 1940s with the Pedregal and continuing as a process of refinement for the remainder of his career.

During this period of transformation, Barragán discovered his country. His subsequent architecture can be seen as a distillation of the proportions and details of old Mexican colonial convents, monasteries, and haciendas. A profound Catholic, Barragán was also influenced by the spirit of grace and solitude with which these buildings are strongly imbued.

At the same time, a number of Barragán’s most characteristic decorative motifs began to make their appearance. These included the groupings of giant pulque fermenting pots on the patio of his later houses, and the use of colored, mirrored balls which had originally hung inside nineteenth-century pulquerías (liquor stores). They appeared in symbolic clusters on Barragán’s coffee tables. Barragán’s palette, which had hitherto been limited to Indian red, blue, and off-white, suddenly adopted the vibrant hues of Mexican traditional clothing and festivals: yellows, pinks, reds, and purples. These design decisions were all influenced by Chucho Reyes.

During the 1950s and thereafter, Barragán became involved in more landscaping and residential planning projects. He built a chapel in 1955 at Tlalpan in Mexico City, and designed others which remained unbuilt.

Barragán was never prolific, but it is nonetheless disappointing that during the period encompassing the last thirty years of his active life he produced only three houses: Casa Galvez in the 1950s, San Cristóbal in the 1960s, and Casa Gilardi in the 1970s.

Partly because very little of his equally remarkable landscaping work has survived, Barragán is best known for his houses. Each house was a variation on a continuing theme. Barragán was uninterested in technical innovation, and was content with a simple vocabulary of materials, such as adobe and timber beams.

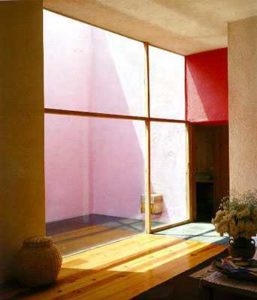

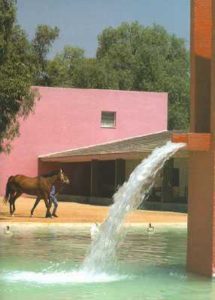

His houses were monastic in spirit and provided a refuge from contemporary life. The closely integrated interior and exterior spaces were surrounded by walls designed to create a private and serene environment. Window sizes were limited except when facing a private courtyard, with its pool and fountain. As Barragán explained: “Architecture, besides being spatial, is also musical. That music is played with water. The importance of walls is that they isolate one from the street’s exterior space. The street is aggressive, even hostile: walls create silence. From that silence you can play with water as music. Afterwards, that music surrounds us.”

The wall is the most Mexican of building elements, and with Barragán it received new expression, becoming a sculpture and achieving an extraordinary plasticity and monumentality. Doors, windows, and other interruptions of the wall surface were placed with the utmost deliberation. Barragán was constantly making changes during construction, often pulling a wall down and starting again.

He used walls to create an all-enveloping domestic enclosure, allowing glimpses of the sky but little else of the outside world. Views focused instead on the patio, which was itself surrounded by high walls. His complaint with most modern houses was their profusion of windows which allowed indiscriminate views of the outside world and competed for the occupant’s attention. In Barragán’s houses the interior is cozy, protective, and without distraction.

Barragán placed walls in a way that orchestrated a systematic “unveiling” of the interior as the visitor entered the house and progressed from space to space. His intention was theatrical; it provided what he liked to refer to as an “architectural striptease.”

Color was used on wall surfaces for spatial effect or to express moods. A wall might be painted blue as a metaphor for the sky, or yellow to give an effect of sunlight.

In the address he gave on receiving the Pritzker Award, he gave an indication of the importance he placed on the intangibles of architecture: “In alarming proportions the following words have disappeared from architectural publications: beauty, inspiration, magic, sorcery, enchantment, and also serenity, mystery, silence, privacy, astonishment. All of these have found a loving home in my soul.”

Other Articles from the ‘Architecture of Mexico’ Series:

Architecture of the Pacific Coast -|- Architecture of the Hacienda