Louis Nevaer

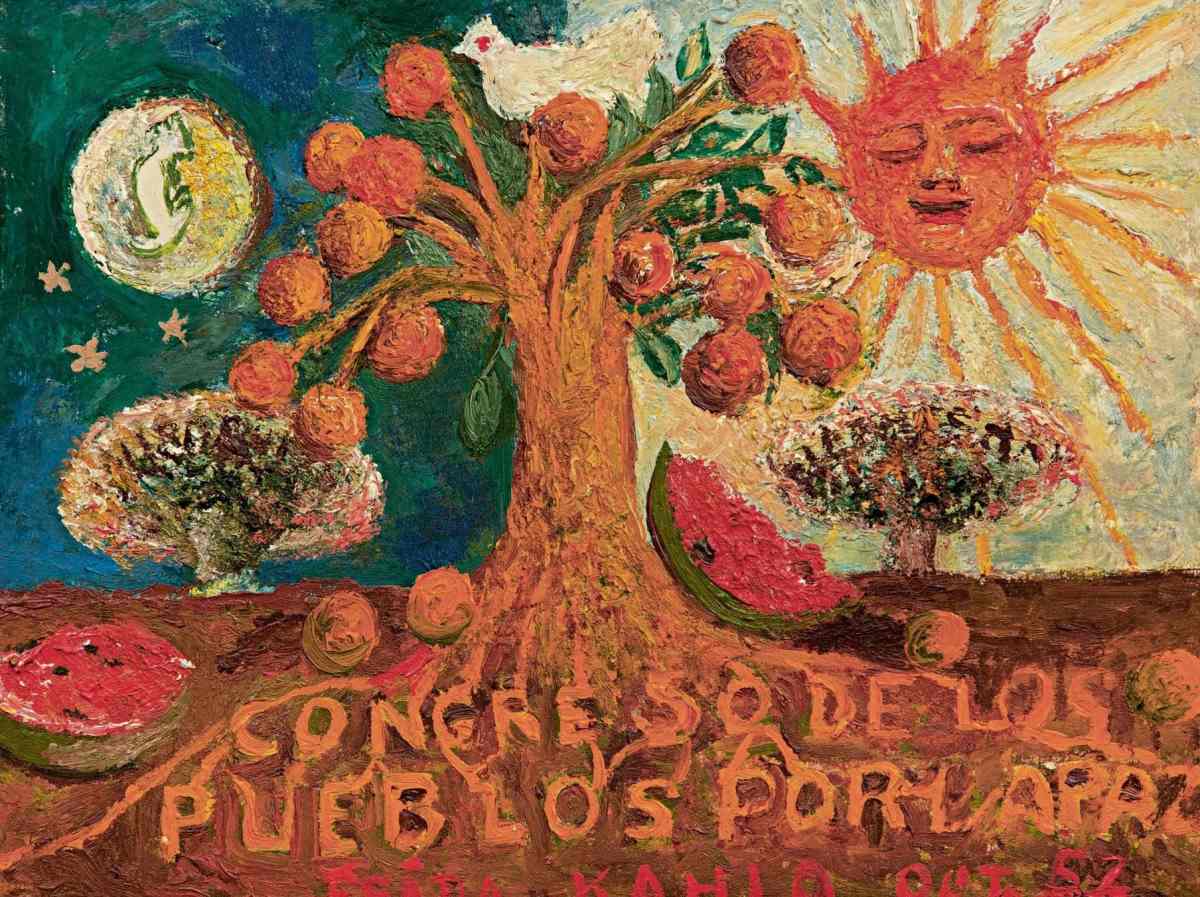

On 29 June 2020, Sotheby’s held an auction that included one of the last paintings Frida Kahlo ever painted. The small work, which she completed while confined to her bed, was her contribution to the Peoples for Peace Congress held in Vienna in 1952. Sotheby’s estimated that “Congreso de los pueblos por la paz” would sell between US$400,000 and $600,000. It sold for more than two million dollars above the highest estimate: the gavel came down at $2,660,000, an astounding price for a work that, by consensus, is a minor one in the artist’s oeuvre.

I followed this auction closely for two reasons. First, my grandmother visited Frida Kahlo in Mexico City when she was working on the painting. They had been acquaintances for decades, having met when Frida and her husband, Diego Rivera, had visited her in Yucatán. Grandmother had written about this visit in one of her many journals. It confirmed the second reason for my interest: Frida was deliberate in making that painting a statement about Mexico’s African legacy.

* * * * *

Mexico was convulsed by the election of Lázaro Cárdenas in 1934, when the Great Depression gripped the world. He launched a six-year plan to rescue the nation’s economy, focusing on social programs to address the immediate needs of the Mexican people. This was consistent with the approach other countries took: Franklin D. Roosevelt was crafting what would become the New Deal, transforming expectations of the federal government’s role in providing for the general welfare of the American people.

Politics aside, what captured the Mexican imagination was the simple fact that Cárdenas was widely believed to be Afro-descendant. Colonial Mexico, everyone knew, boasted more Africans than any other region of Spanish America. In the words of Colin Palmer, the renowned Jamaican American historian, “Africans in Mexico left their cultural and genetic imprint everywhere they lived. In states such as Veracruz, Guerrero, and Oaxaca, the descendants of Africa’s children still bear the evidence of their ancestry. No longer do they see themselves as Mandinga, Wolof, Ibo, Bakongo, or members of other African ethnic groups; their self identity is Mexican.”

With Cárdenas elected, there was an awakening among intellectuals that Mexico’s African legacy should be explored, examined, and embraced. After all, if Mexico’s African legacy was evident in the face of the beloved president, then who else might boast a similar legacy?

* * * * *

The decision of Americans to exclude indigenous peoples from their society—codified in the “Indian removal” acts—made U.S. society one in which Black America and White America are pitted against each other. In this showdown, White America has always had the upper hand, inventing tropes to intimidate and humiliate Black America. Blackface and minstrel shows, for instance, are examples of the racist hostility of White America toward Black America. This extends even to produce. Consider, for instance, the principal fruit introduced to the Americas from Africa: the watermelon.

The watermelon, Citrullus lanatus, is a flowering plant first domesticated in West Africa. It arrived in the Americas aboard the same ships that brought enslaved Africans. In the United States, after the Civil War, the watermelon became a trope to ridicule Black America. Just as statues of defeated Confederate military officers were erected in public places throughout the vanquished former Confederacy during segregation to intimidate Blacks, culinary traditions were weaponized.

“[T]he stereotype that African Americans are excessively fond of watermelon emerged for a specific historical reason and served a specific political purpose. The trope came in full force when slaves won their emancipation during the Civil War. Free black people grew, ate, and sold watermelons, and in doing so made the fruit a symbol of their freedom. Southern whites, threatened by blacks’ newfound freedom, responded by making the fruit a symbol of black people’s perceived uncleanliness, laziness, childishness, and unwanted public presence,” William Black wrote in The Atlantic.

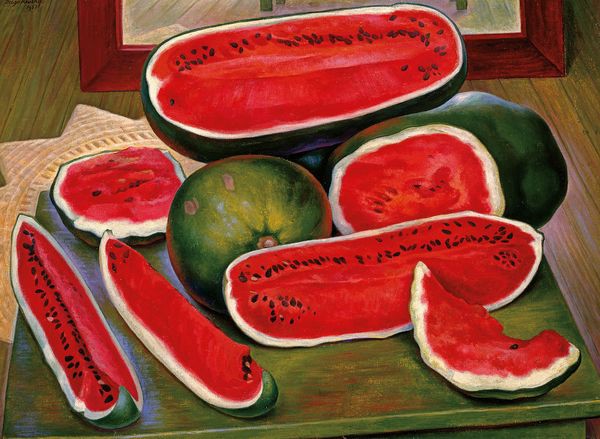

In Mexico, however, the watermelon came to symbolize the culinary legacy that the first Africans brought with them, a sweet gift to be enjoyed.

Thus, it’s not a coincidence that two of the giants of twentieth-century Mexico—Rufino Tamayo and José Vasconcelos—came from Oaxaca, a state that boasts one of the largest Afromexican populations in Mexico. Vasconcelos served as Secretary of Education (1921–1924) in the Obregón administration to great success. He championed the idea of the mingling of the races so as to form a new, hopeful “cosmic race.” This idea, of course, echoed Walt Whitman’s declaration in “Song of Myself” of what it meant to become an authentic American: “Of every hue and caste am I.” E pluribus unum, anyone?

Vasconcelos suspected he had African ancestors; Tamayo was convinced of his.

The proliferation of watermelons in Tamayo’s still life paintings was homage to his—and Mexico’s—African legacy. “Seré zapoteca, pero cuento con la herencia de África” (“I may be Zapotec, but I have an inheritance from Africa,”) he said, boasting of the cultural and racial mix of contemporary Oaxaca. Watermelons thus began to proliferate throughout Mexican art. Today, it seems every middle-class Mexican home has a painting of a watermelon somewhere.

It’s important to note one historic curiosity that shaped the nature of Mexico’s African identity: African men were welcomed in Colonial Mexico, but not African women. The Viceroys saw slavery as a temporary evil. They didn’t want to emulate the British colonies — or other Spanish holdings in the Caribbean — and find themselves in a situation where slaves were giving birth to slaves. In consequence, African men in Colonial Mexico married indigenous women, and their mixed-race children were born free.

Hues and castes intermingling over the centuries in this manner give rise to doubts about one’s specific ancestry. Now, enter science. Today, it’s possible for anyone to analyze his or her DNA. Family lore and histories, embraced or repressed, can have a definitive answer. When Francisco Toledo, the acclaimed artist who died in 2019, for instance, took a DNA test, it confirmed what he knew in his heart all along. He was ecstatic with delight when I met him through Henry and Rose Wangeman, proprietors of Amate Books in Oaxaca City: “¡Con solo escupir en el tubito, así de fácil se confirmo mi historia!” (“All I had to do was spit into this tube, and then my history was confirmed!”) he told me.

But if Tamayo chose the subtlety of watermelons to affirm exclusively the culinary legacy from Africa, Toledo was more blunt. Yes, he used watermelons as a subject of his art, but in Slave Ship (2015), his head is floating high, though he is manacled and chained to a ship of enslaved men and women. Tamayo envisioned himself the heir of the free African Conquistadors who fought alongside the Spanish; Toledo allied himself with those who were brought over enslaved. (Colonial Mexico relied on African slaves to remedy the labor shortages in Spanish America occasioned by the epidemics that decimated the indigenous peoples throughout the entire hemisphere.)

This leads us back to Frida’s painting. In her journal, my grandmother wrote:

I went to visit Frida. She didn’t look well. What can be expected given all the strong pain relievers she’s taking? She was working on her new painting, which she is going to send to the Congress to be held in Vienna. Her body’s exhausted and her painting suffers for it. The precise brushstrokes and details have slipped into history. … She also told me that she added two watermelons as a tribute to Tamayo. ‘Now that Rufino discovered that among his ancestors he has the first Africans who accompanied the Spanish, the watermelons he paints are recognition of the sweetness of Africa,’ she told me. … ‘I’m encouraging my toad [Diego] to paint his own watermelons too,’ she commented, laughing. ‘The time’s right,’ I said. And then we continued with our talk of gossip … When we said goodbye, she asked, ‘Is this the last time you are going to visit me, Raquelita, Raquelita?’ ‘Of course not, my dear,’ I replied. But she was right. … I fear that when I return [to Mexico City], it is very likely that she will have died by then.” (See note below for full text of journal entry.)

In Mexico, watermelons also honor the dead. There is no definitive answer as to how this started, but it did. The more reasonable explanation is that when an African man arrived in Mexico, lived with an indigenous woman, and raised a mixed-race family, there was resignation that his descendants would not be entirely African. As the decades passed and these men died, the family gathered around and combined Catholic, indigenous, and African burial rites. One tradition from Oaxaca was offering foods and beverages to the dead.

Watermelons loomed large at the funerals for Mexico’s first Africans—in honor of the bounty of the lands of their birth. In time, the fruit became associated with Day of the Dead—Día de los Muertos—in Oaxaca. (Day of the Dead is a regional festivity, although today it has a national and international following.) The inclusion of watermelons in Mexican art is more symbolic than aesthetic; it’s a nod of appreciation to the nation’s African diaspora.

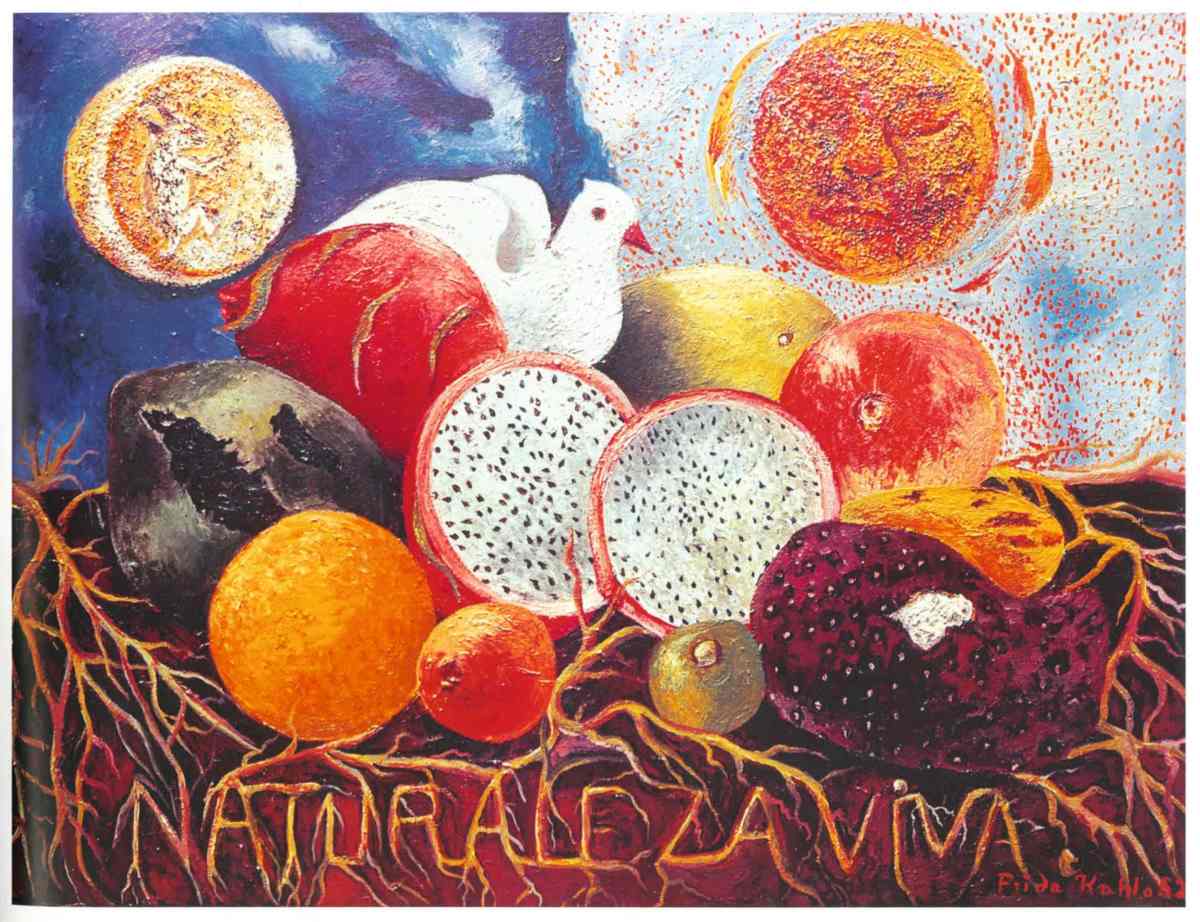

Frida plagiarized herself in “Congreso de los pueblos por la paz”, copying almost everything from “Naturaleza viva”, also painted in 1952. Both paintings contrast night and day; both have a white dove; both have roots forming words. In Congreso, however, there are two explosions, one at night and the other at daytime. There is also a tree in the foreground, bearing fruit. There are sliced watermelons, one for day and the other for night, life and death. “However debilitated she was when I saw her,” I remember my grandmother telling others in several conversations over the years, “she was very sure of including watermelons in the painting she wanted exhibited in Vienna.” Frida, indeed, included the watermelons to make the larger point that other artists were making at the time: Modern Mexico is not Mexico without its African heritage.

And so, in honoring Mexico’s African legacy, Kahlo was, in a way, anticipating her own symbolic—and aesthetic—death. When she finished this painting, she had less than two years to live. After she died Diego—her beloved toad—fulfilled her wish. He painted watermelons.

Note: Full text of journal entry

“Pasé a visitar a Frida. No la vi bien. ¿Qué se puede esperar, con todos los fuertes analgésicos que esta tomando? Estaba trabajando en su nueva obra, la que va a envíar al Congreso que se realizará en Viena. Su organismo esta agotado y su pintura sufre por lo tanto. Sus pinceladas precisas y los detalles han pasado al pasado. Y su nueva obra me pareció muy similar a “Naturaleza viva,” particularmente con el uso las raíces del árbol para escribir letras. Me dijo que quería viajar a Viena para asistir al Congreso, pero, en sus condiciones, eso es una ilusión. También me comentó que añadio dos sandías como un homenaje a Tamayo. “Ahora que Rufino descrubió que entre sus antepasados cuenta con los primeros africanos quienes acompañaron a los españoles, las sandías que pinta son reconocimiento a lo dulce de África,” me dijo. “Así debe de ser si queremos ser la raza cósmica como nos enseña Vasconcelos,” le respondí. “Estoy animando a mi sapo [Diego] a que él pinte sus propias sandías también,” me comento, riéndose. “Es hora,” le dije. Y seguimos con nuestra plática de chismes … Al despedirnos, preguntó, “¿Será esta la última vez que me vas a visitar, Raquelita, Raquelita?” “Claro que no, mi vida,” le respondí. Pero tenía razón. Estaba mal — y no sé cuando voy a regresar a mi adorada capital azteca. Temo que cuando regrese será muy probable que, en ese entonces, no la alcanzaré con vida.”

References:

- William R. Black. 2014. “How Watermelons Became Black,” The Atlantic, December 8, 2014.

- Colin Palmer. Undated. “A Legacy of Slavery.” Smithsonian Education website, [3 Sep 2020]

- Walt Whitman.“Song of Myself,” Section 16.

Published or Updated on: September 24, 2020 Louis Nevaer

Louis Varela Nevaer, Director, Casa Catherwood in Merida