James Musselman

More than 8 million people in Mexico, about 6% of the total population, speak one or more of the country’s 68 original (indigenous) languages. [1]

Najo’obiñ’eje, Welcome, bienvenidos, in Mazahua.

Pjiekak’joo, “We speak”, the name of the critically endangered Tlahuica language.

Despite an official proclamation following the Mexican Revolution of the elimination of racial prejudice against original peoples (accompanied by arguments for the superiority of original peoples, as enshrined in indigenismo), the proportion of the population speaking an original language has dropped sharply since 1910. According to the census that year, about 13% of the Mexican population was monolingual in an indigenous language. However, some historians and anthropologists have suggested the actual figure was closer to a third, or based on culture, more than half the population was indigenous, but that the numbers were suppressed due to institutional racism and the centuries of miscegenation that had greatly eroded the neat racial categories of the early colonial period. [2]

As Latin American historian Alan Knight has pointed out, prejudice remained alive and well even after the official proclamation (1990). This was not only expressed in attitudes, but in paternalistic public policies such as the one language policy of the Federal Department of Education (SEP, its acronym in Spanish).

The Intercultural Universities (UIs) have emerged in just the last two decades and are intended to help change the endemic discrimination suffered by native peoples in Mexico by directly supporting their languages and cultures.The IUs are a relatively new educational paradigm in Mexico. This new model for schooling represents a redress of the centuries-old practice of privileging Spanish and stigmatizing original languages. During the nearly 200 years of Mexican federal educational policy, Mexico has not been at the forefront of linguistic rights. Navarrete and Alcántara note that even today half of indigenous people in Mexico have not completed primary education. [3] This violates article 26 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, which Mexico signed in 1948 as an original signatory, and which begins “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory.” [4] Of course, Mexico is not the only country to have failed to comply with that goal. [5]

The Intercultural Universities

The term “intercultural” is an attempt to place all cultures and languages on a completely equal footing and was chosen over “indigenous” in order to avoid the connotation of segregation.[6]

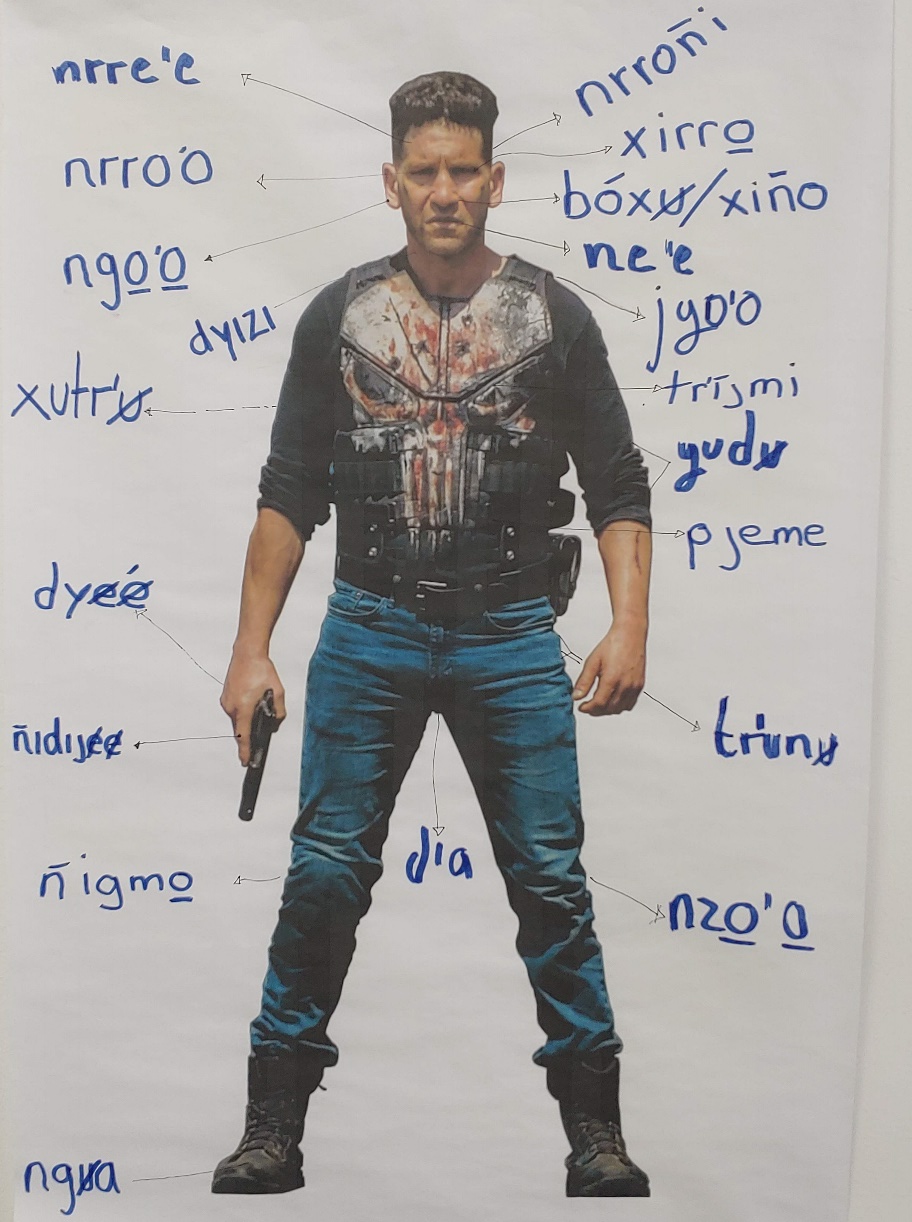

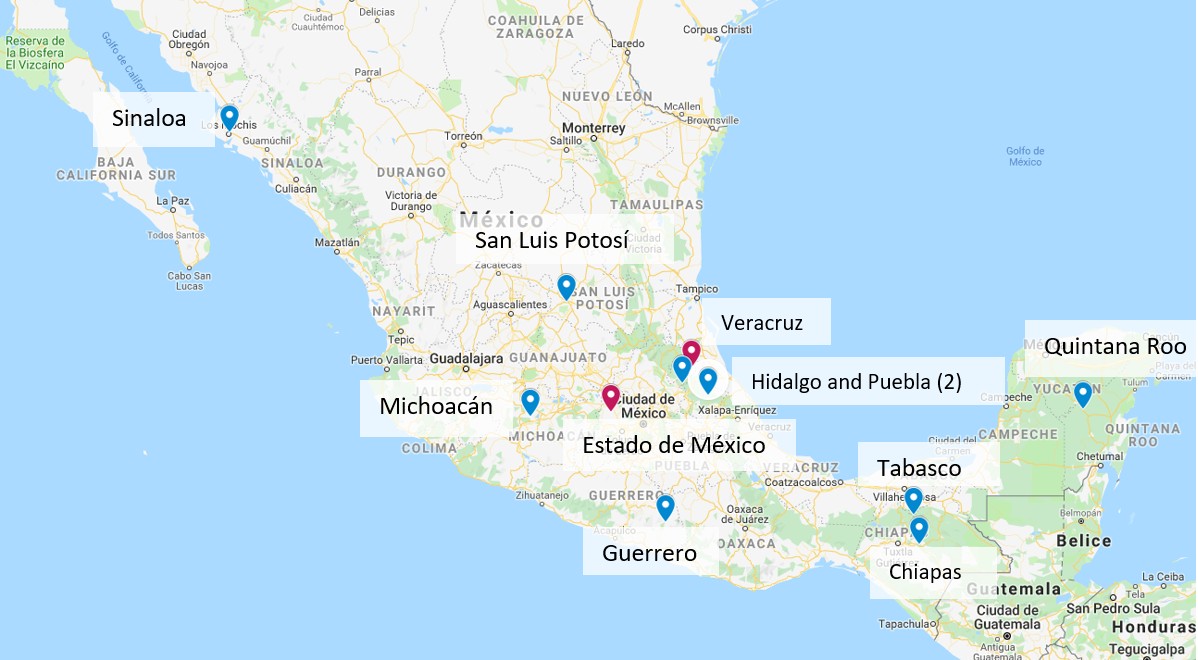

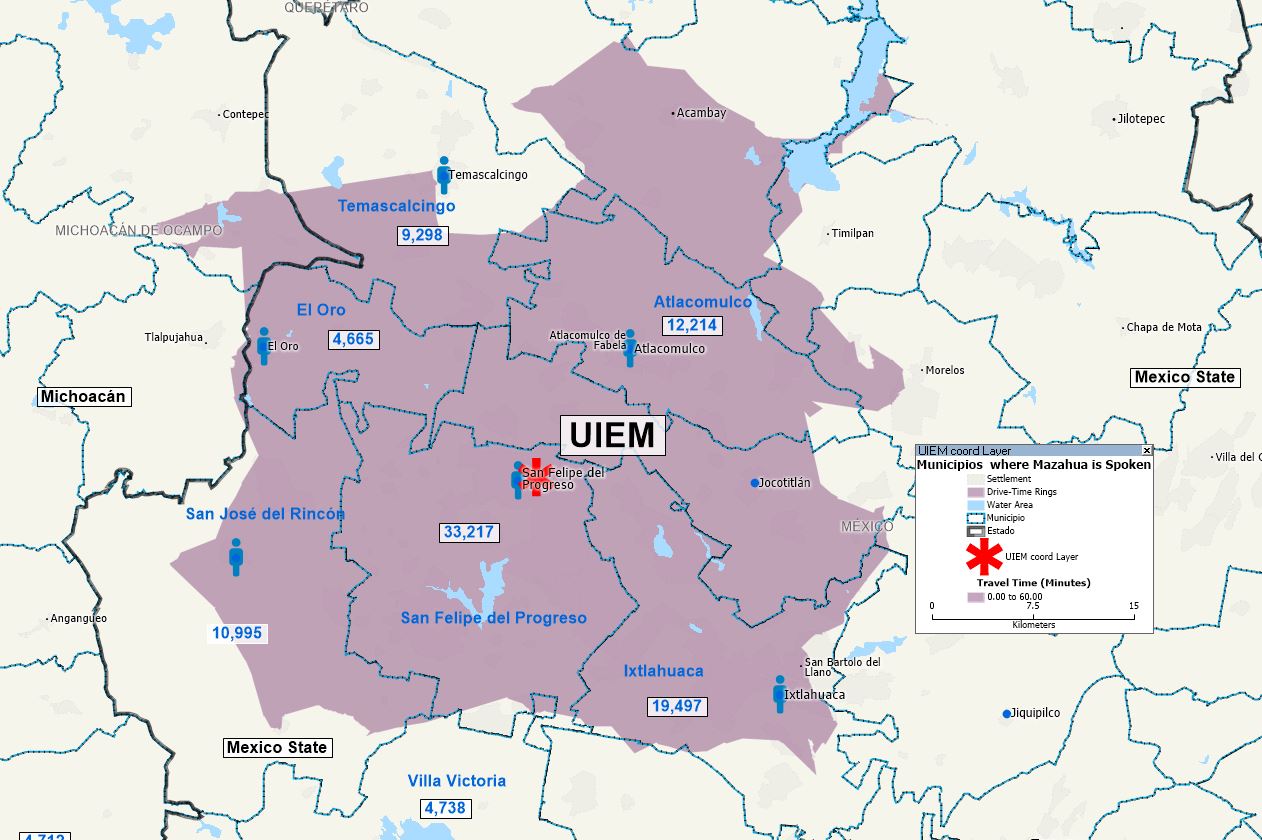

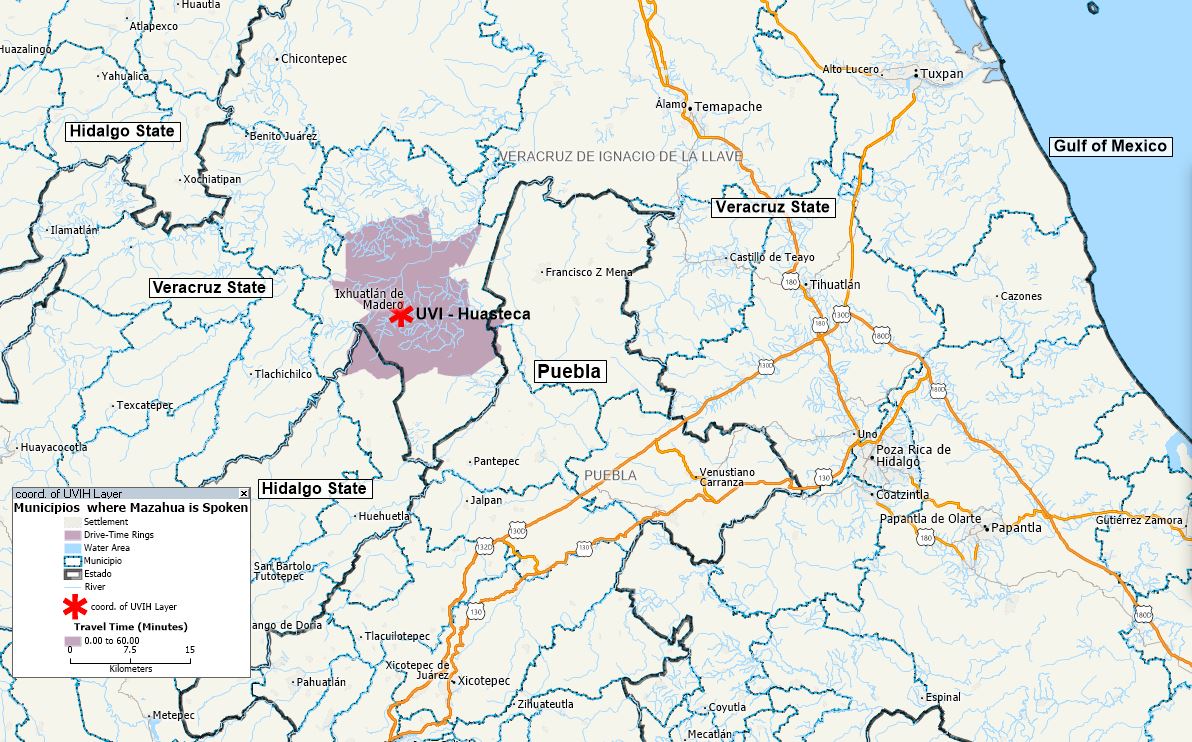

There are twelve IUs in Mexico (map). The two universities featured here are the Universidad Intercultural del Estado de México (UIEM), located in San Felipe del Progreso, Mexico State, a couple of hours northwest of Mexico City, and the Universidad Veracruzana Intercultural (UVIH), located in Ixhuatlán de Madero, a very isolated campus in the Huasteca Veracruzana in the state of Veracruz.

UIEM was the very first one to be founded, it opened in a strip mall in 2004 due to the campus still being under construction. Today, UIEM has about 1,400 students compared to the traditional autonomous university in Toluca, UAEM, which has about 80,000 students.

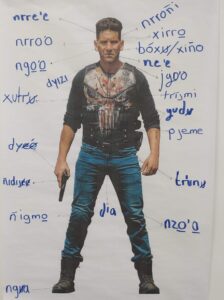

UIEM was created by a deal between then-candidate and populist Vicente Fox and Mazahua activists in exchange for political support. [7] During that time in the 1990s, Fox was claiming he could solve the Zapatista “problem” in Chiapas in 15 minutes. In the area of UIEM there are five original languages spoken. The principal one being Mazahua with about a hundred thousand speakers, followed by Otomí, Matlatzinca, Tlahuica, and Nahuatl.

At UVIH, the majority of students are native speakers of Nahuatl. About 1.4 million people in central Mexico speak Nahuatl. Some students speak Otomí, Tepehua (a Maya language, no one is sure how the Maya got that far north), and Totonaco (spoken by La Malinche, mistress to Hernán Cortéz). UVIH is about 100 km. from the city of Poza Rica, although the condition of the roads is such that it is about 3 hours by car.

The mission and vision of the IUs is to directly support regional languages and cultures by being placed in areas that serve these communities. Needless to say, these same communities have traditionally been severely underserved.The IUs generally offer bachelor=s degrees in nursing, intercultural health, language and culture, intercultural law, and sustainable development. At UIEM students take four years of English and four years of an original language, about 70% study Mazahua. At UVIH students are required to take one year of English. At both schools, there is a heavy participation in the community through academic investigation and, at UIEM, community nursing.

The IUs are treading a fine line between offering a heterodox understanding of knowledges, putting scientific knowledge and indigenous knowledge on an equal footing, while at the same time trying to create a community of professionals that mitigate out-migration. The regions often suffer out-migration and young creation of families. In the case of UIEM, a community issue is young people who work in Mexico City and come home on the weekends only to spend their income on alcohol and drugs. The mission of UIEM is to provide a route to higher education and a profession in order to mitigate these issues in the community.

Are the Intercultural Universities a success?

It remains to be seen if the IUs can contribute on a regional scale, with a community focus and presence, to the strengthening of local languages and cultures. In this the IUs are distinctly different from the traditional indigenous institutions, represented by organizations such as Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI) and the prestigious an highly respected Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), or even the older Instituto Nacional Indigenista (INI, founded 1948) which metamorphosed into the Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas (CDI) in 2003, during a time when President Fox was trying to “fix” indigenous issues. The traditional institutions suffer from a lack of community involvement and have a disinterested, ivory tower orientation projected from Mexico City, except possibly in the case of the CDI which is oriented toward physical infrastructure projects such as potable water, but, nonetheless, is scantily involved in cultural or educational development. The grassroots and originally activist-oriented IUs were created to bring language support directly to the communities in a non-paternalistic manner and currently have an important physical presence in the communities and are actively trying to support original languages and culture.

As noted by interviewee Adelina, in her hometown in the Mazahua region, the sixty-year-old Mazahua couple who helped her with her studies could not believe there was a university (UIEM) that supported the Mazahua language, harking back to the one language policy of the paternalistic SEP. One has to ask where have INALI (and its predecessors) and INAH been over the last 50 years. Adelina, who worked a few years at INAH in Mexico City, related how some of her co-workers assumed she was from INAH itself or the prestigious UNAM national autonomous university. According to Adelina, when her co-workers found out she was from UIEM and spoke Mazahua, they just sort of sat there dumbstruck for a few moments. Future research is needed to continue to monitor the experiment that are the IUs in order to gauge their influence in original language support, especially at a national level, which is particularly important and which is part of their missions.

Conclusion

The woeful lack of a supporting educational ecosystem is a significant threat to the long-term viability of the IUs, or at least a threat to their missions and visions. The almost complete lack of meaningful bilingual primary schools and the lack of language support in secondary and high schools is a serious threat and forms the basis of the abject impotence of the IUs to promote or preserve the presence of native or bilingual speakers of original languages. Among the interview participants, Griselda came from a town predominately of Nahuatl speakers, and yet, shockingly, there is no bilingual school in her town. On the other hand, Adelina, who was the director of an Otomí bilingual preschool, described a bilingual school where Otomí was mostly used to communicate with parents, not with students, wherein the academic program was designed to rapidly induct the students into the Spanish-language mainstream.

It is challenging to reconcile the stratospheric official federal policy of making all schools intercultural with the reality of a lack of educational infrastructure to provide linguistic support and rights to original language speakers. This lack of a bilingual infrastructure at all educational levels short of higher education is a serious systemic challenge that astronomically impedes the IUs’ attainment of their missions of strengthening regional languages. In the future, the federal authorities need to procure funding and implement a coherent bilingual educational policy, which is no small task, neither financially nor societally. This dire situation needs to be researched in order to determine its causes and its remedies by means of reforms and to propose major changes in program architecture.

About the Author

I was extremely fortunate in that two university administrations gave me permission to be on-campus doing research and teaching. This article is based on the work that I did to complete a PhD in Hispanic Languages and Literatures. My field is linguistics, specifically sociolinguistics. I dedicated my dissertation to the indigenous languages and peoples of the Mexican states of el Estado Libre y Soberano de México and el Estado de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave. That work was a token of my commitment to them, their beautiful cultures and languages, and my concern for their welfare.

Many academic studies of indigenous languages revolve around language documentation, which of course is a valid scientific pursuit. My dissertation, however, explored language attitudes (ideologies) in a higher education setting and the influence of the Mexican intercultural universities (IUs) on language attitudes towards indigenous languages in students and in the surrounding communities, while holding that indigenous languages and cultures are part of world heritage as stated by UNESCO. [8]

References and bibliography

[1] INEGI, 2009.

[2] Gamio, 2010, p. 27; Knight, 1990, p. 74.

[3] Navarrete and Alcántara 2015, p. 152.

[4] Declaration, 2015.

[5] Human Rights Ignored, 2018.

[6] Casillas & Santini, 2009, p. 135.

[7] Gorman, 2016, pp. 29, 57.

[8] UNESCO, 2015.

- Casillas Muñoz, M. de L., & Santini Villar, L. (2009). Universidad intercultural: Modelo educativo (Segunda edición). SEP, Secretaría de Educación Pública, CGEIB, Coordinación General de Educación Intercultural y Bilingüe.

- Gamio, M. (2010). Forjando patria: Pro-nacionalismo = Forging a nation (F. Armstrong-Fumero, Trans.; original 1916). University Press of Colorado.

- Gorman, T. G. (2016). Partial democracy and compromised multiculturalism: The fate of the intercultural universities in Mexico [Doctoral dissertation Political Science, Indiana University (Proquest No. 10196175).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2009). Perfil sociodemográfico de la población que habla lengua indígena. Mexico City, Mexico: INEGI.

- Knight, A. (1990). “Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo: Mexico, 1910-1940.” In R. Graham (Ed.), The Idea of Race in Latin America, 1870 B 1940. University of Texas Press.

- Navarrete-Cazales, Z., & Alcántara Santuario, A. (2015). “Universidades interculturales e indígenas en México: Desafíos académicos e institucionales.” Revista Lusófona de Educação, 31, 145B160.

- UNESCO. (2001). Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. United Nations.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (2015, October 6).

- World Watch Monitor. 70 years since universal declaration, human rights “ignored and abused all over the world.” (2018, December 7).