Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D.

Last year I participated in a panel discussion in Oaxaca about a new book entitled La E del Mezcal: Exportación, by Dra. Blanca Esther Salvador Martínez. While the other panelists essentially praised the author for writing such an important book and explained how it thoroughly covered all the bases regarding the subject matter, I took a different approach. I explained how the export of mezcal positively impacts virtually every aspect of the Oaxacan economy. This piece reviews and expands on what I discussed at the book presentation.

Oaxaca is one of the poorest states in the country. We have agriculture and tourism, and little if anything else. Factories for export products are virtually non-existent. We’ve always had significant production of tomatoes, mangoes, black beans, avocados, etc., for both domestic consumption and for export, and so growing fruits and vegetables has kept the economy humming, at least within the context of its standing relative to the rest of Mexico.

But tourism is another story. It is characterized by peaks and valleys. Many readers will recall what happened in 2006, when as a result of severe social unrest, tourism dipped to pretty well nothing. And then between in 2020 and 2022, this time because of COVID, once again tourism was essentially absent. Next year, or the following year, or in five years, once again tourism will likely take a hit.

Both the US State Department and journalists often warn prospective visitors against traveling to Oaxaca. I even recall about three years ago seeing a story on the international cable channel Al Jazeera about fires blazing at the Huitzo toll booth, which is about an hour’s drive north of the city of Oaxaca. The underlying message was clear: it’s too dangerous to visit Oaxaca. But mezcal tourism appears oblivious to the ravages of fearmongering.

For the past dozen or so years, I’ve been working on a part-time basis teaching visitors to Oaxaca about mezcal production stages and processes. I also work with documentary film production companies, photographers, and most importantly with individuals and groups interested in exporting mezcal. Hence, in the panel discussion I stressed the work done by Dra. Salvador in fostering the state’s economic growth through assisting those with plans for the export of mezcal. Between the two of us, we have worked with people who now have their own export brands and who are importing the spirit to the US, to Canada, to the UK, to Australia, to Europe, etc. And so, we find that with every pallet of mezcal that leaves Oaxaca, the state’s economy is bolstered. And this refers to much more that the sale of raw material (i.e. the heart of the plant, or piña as it is traditionally termed). Sure, some newbies to the spirit will decide it’s not for them. But the lion’s share will be enthralled with it, some even deciding to jump into the business of mezcal.

It doesn’t matter if the visitor to Oaxaca wants to visit the palenque (distillery) of his new favorite agave spirit, to photograph, to film, or to pursue an export project; they will be staying in a city lodging, be it Quinta Real, Holiday Inn Express, or a B & B or airbnb. And they’ll be dropping pesos at eateries both in the city and in the villages; high end, middle-of-the-road, as well as street food and at market stands. This all translates to amelioration of the Oaxacan economy.

But there is so much more! While, believe it or not, some mezcal tour visitors have no idea about the archaeological sites, the craft villages, the push towards ecotourism, the fact that the city is the country’s mecca for cuisine with its cooking schools—Casa Oaxaca, Los Danzantes, and more—upon arrival they do begin to realize the state’s diversity of offerings.

The arts scene has hugely capitalized upon the mezcal boom. More than two decades ago, our goddaughter Lucina (then only six years old), from the terracotta clay pottery village of San Marcos Tlapazola, began making small mezcal drinking cups with a face on one side and an agave on the other. At the time such an item was unknown. Today, several woman from that village are marketing those little vessels. Lucina’s mother, a talented craftswoman in her own right, is continually inventing other clay products with an agave motif. While she strives to stay one step ahead of the village competitors, others nevertheless copy. The economic lot of the village has improved over the past decade or so, by leaps and bounds, due to the interest in anything related to mezcal and agave.

When tourism dropped dramatically as a consequence of COVID, and I witnessed many of my friends in other craft villages suffering, I encouraged them to produce craft items with mezcal and agave designs. A family in the woolen rug village of Teotitlán del Valle is now making tapestries with a palenquero working his horse with the tahona (stone crushing wheel). Another family in the carved wooden figure (alebrije) village of San Martín Tilcajete is now making similar themed engravings, as well as solid wooden plaques each with a different species of agave pictured.

A friend who hand-forges knives and machetes out of recycled metals, now engraves them with, once again, agave and mezcal motifs. At my request, one of the Aguilar sisters known for their handmade and painted clay figures, now makes figures of Mayahuel, the pre-Hispanic goddess of agave. She is pictured with large breasts and/or rabbits at her feet, the way we see her represented elsewhere. One of the candle makers, once again in Teotitlán del Valle, handmakes a series of candles, each featuring a different species of agave. Several years ago, I encouraged a family of artisans in the cotton textile village of Santo Tomás Jalieza to make table runners with agaves complete with quiotes extending upwards. The wife complied with my request, only to add to the design by including hummingbirds sucking at the flowers on the stalk. In each of the foregoing cases, the mezcal boom has made a positive impact on the economic lives of not only those particular villagers, but others who have realized that a new segment of the tourist population will buy, not the usual craft items, but rather anything related to agave spirits.

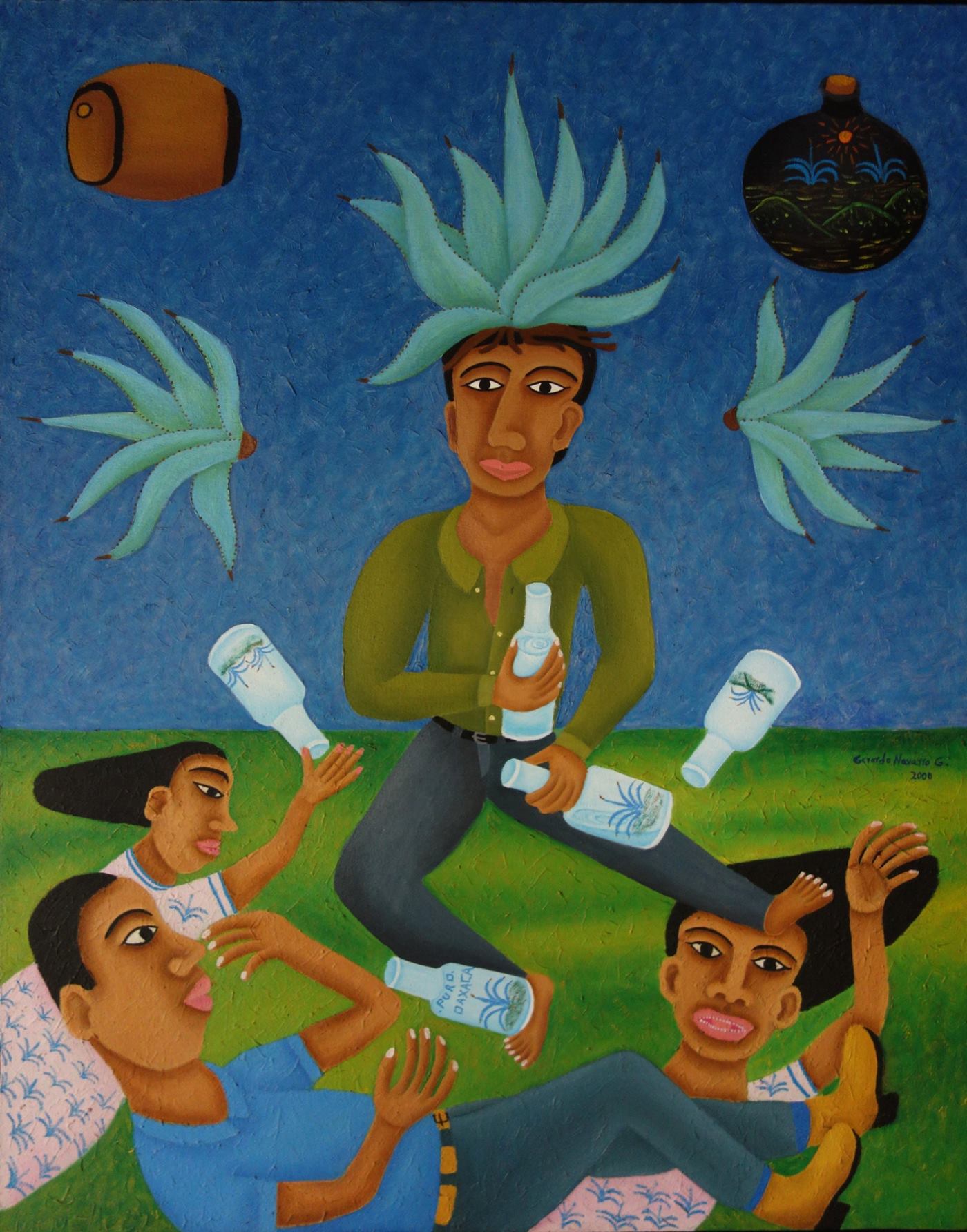

A dramatic change is evident in the nature of the art produced in the engravings workshops on Calle Porfirio Díaz and more generally in the works on display for sale in the open air downtown market known as Parque Labastida. One now sees roughly a quarter of the art being offered for sale featuring, yes, agave and mezcal-themed graphics, oils, and water colors.

The agave distillate boom is directly resulting in repairing village and secondary highway roads, building gas stations, constructing schools and increasing the compliment of their teachers, building village water filtration plants, and giving children a chance to improve their education. Previously, many teens, especially males, left their homes for better financial opportunities in Mexico City, California and Texas. Today their labor is needed in making and marketing mezcal in more cost-effective and environmentally friendly ways.

A brother and a sister from Rancho Blanco Güilá each recently graduated from college with a degree in civil engineering, their families being able to fund their higher education using the extra disposable income derived from the sale of the family’s mezcal production. They are both assisting their family to improve their methods of making mezcal, and in fact has recently achieved certification for their own palenques and respective brands. Improved education means improving opportunities to realize dreams.

We don’t know what the future will bring in terms of the continued growth, or not, in Oaxaca’s agave distillate industry. However, with more children now getting a college education, if the industry begins to falter, those youths will have their education upon which to fall back. Two decades ago they would have been relegated to subsistence paying jobs. For the benefit of the state of Oaxaca, we can just hope that the current trajectory continues.

Published or Updated on: June 25, 2024