Sean Power

For far too long the history of 19th Century Mayan free rule in the Mexican Yucatán has been largely ignored. But local Maya are working to put it on the map. Through museums, ruins, guided tours and more, they are preserving the legacy of this largest post-colonial indigenous revolution in the Americas, commonly known as La Guerra de las Castas (The Caste War) and alternatively as the Mayan Social War.

Most of the top sites are within 200 kilometers of tourist centers like Valladolid and Playa del Carmen, making them accessible as a day trip. For those wanting a deeper dive, a multi-day tour of these off-the-beaten-track Mayan communities awaits.

Background on Mayan Resistance

In contrast to the Aztecs and Incas, the Spanish failed to swiftly conquer the Mayan Yucatán. The many autonomous kingdoms spread throughout the region meant each one had to be defeated separately. As proof of this difficulty, not until 1697—almost 175 years after their first contact with Hernán Cortés—did the last independent Mayan kingdom, that of the Itza Maya, finally surrender. Even then, the fires of resistance were not extinguished. Over the coming century, waves of Mayan uprisings occurred. Most were short-lived. But, in the early 19th century Yucatán elites inadvertently aided their cause.

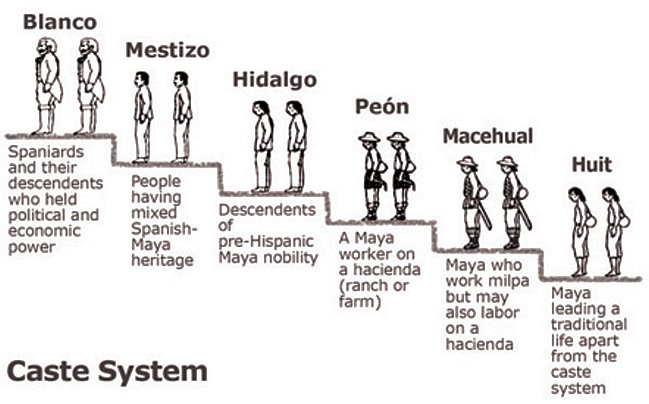

At that time the Yucatán was loosely affiliated with Mexico, and the peninsular white elite wanted independence, especially as the central government increased taxation in the 1830s to pay for the war to keep Texas. For the local Mayans, everyday life was becoming increasingly insufferable. Elites, especially in the peninsula’s east, were confiscating their communal lands for henequen and sugar cane plantations, and forcing them to work in debt servitude. Mayans outnumbered whites and mestizos three to one in the Western Yucatán, and five to one in the east. They were thus prime targets for military recruitment. And, when some of these same elites made promises of lower taxes and land free from tributes in return for their military service, thousands of Mayan males joined the revolts.

Over the coming decade, Mayans were recruited for various military campaigns, both in support of Yucatán independence and in defending the Mexican republic, as two factions had emerged in the peninsula. Regardless, no change in their material conditions had occurred. A powder-keg-in-waiting had been created: the Mayan troops had kept their weapons, and they had been trained and led in battle by Mayan generals.

Panicked about a possible Mayan revolt, the peninsula government of Santiago Mendéz summarily executed Mayan leader Manuel Antonio Ay of Chichimilá in June 1847 on the suspicion that he was planning an attack. In the ensuing weeks, Mayan residents in the nearby town of Tepich were punished, with many killed and their homes burned. On July 30th, Mayan soldiers stormed Tepich. They first entered the church and executed the priest, who had been accused of sexually abusing children, then proceeded to kill all the town’s whites.

Just a year after its start, a federation of roughly 100,000 Mayan troops had conquered all the Mexican Yucatán, save the walled cities of Campeche and Mérida and the narrow Camino Real connecting the two.

Over the coming years, Mayan troops were pushed back to the peninsula’s east. There, three independent Mayan states self-ruled. The largest and most militarily aggressive, the Cruzo’ob, controlled the entire region of what is now the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, and had diplomatic relations with the British in Belize.

In 1901, Mexican troops took control of the Cruzo’ob’s capital, marking the ‘official’ end to the war. Nonetheless, the rebels scattered. The largest community of some 700, the Xcacal (or Tixcacal) Guardia, resisted and continued to self-govern until mid-century. This small community of the same name exists to this day.

Despite this fascinating tale, that includes white slaves building Cruzo’ob religious and governance buildings and captured Mayans being sent to Cuba as slaves, most visitors to the Yucatán leave without learning about this history and how it shaped the peninsula. Over its course, an estimated 250,000 perished. The region lost a third of its population due to death and exile, including half of its Mayans. Neighboring Belize was also heavily impacted. Several thousand persons took refuge and remained there after the war’s conclusion.

A perfect location to become acquainted with this history is at the aptly named Museo de la Guerra de Castas (Caste War Museum). Located in a colonial building in Tihosuco, a small town that was overtaken by Mayan rebels during the Caste War, this is the largest and most comprehensive museum in Mexico dedicated to the Caste War.

The museum provides visitors with an orientation to the 400-year history of Mayan resistance in the region, including the various uprisings against Spanish colonization. Many museum items were donated by locals to preserve them. On display are letters sent between the Mayan rebels’ key leaders concerning their military strategy. Artifacts also tell the story of the several hundred U.S. soldiers of fortune, fresh off the Mexican-American War, who agreed to the Yucatán government’s offer of 320 hectares each and a salary of $8 a month for enlisting. None collected this offer. They were unprepared for this guerrilla-style war with its high casualty rates, and most quickly returned to the U.S.

Just a few steps from the Caste War museum is the spectacular Iglesia de Santo Niño Jesús (Church of the Saint of Baby Jesus). Rather than rebuild its dome, destroyed by Mayan rebels’ shelling during the war, the locals who later resettled the area continued to hold services in the structure as is.

A Tihosuco-based cooperative tourism project, Sociedad Cooperativa Ubelilek Kaxtik Kuxtal, provides guided tours of the church, the Caste War museum, and a demonstration of cotton weaving.

Another symbol of the Caste War’s devastation can be seen during a half-hour walk through the jungle outside of Tihosuco. Here is the Lal kah or Téla. This village of primarily whites and mestizos was abandoned during the Caste War and lays blanketed by vegetation. Over the course of the Caste War, several hundred villages across the Yucatán were deserted.

Aventura Tela, a Tihosuco-based responsible tourism outfit run by Maya youth, offers guided tours of TéLa, as well as biking excursions in the area, visits to cenotes, guided birdwatching, lodging and meals with locals, and even nighttime walks in Tihosuco.

Those interested in additional ruins can visit Jacinto Pat’s former hacienda Xculumpich, another twenty minute walk from Téla.

The small village of Sacalaca, 37 kilometers southwest of Tihosuco, provides visitors with a glimpse into the colonial-era social hierarchy. Here, two churches existed within 350 meters of each other, one exclusively for the Spanish and elites, and the other for the Mayan populace.

During the Caste War, the church for the Spaniards (Iglesia Virgen de la Candelaria y los Tres Reyes) was damaged and its roof destroyed by Cruzo’ob fighters. Present-day villagers have left it as is. The former, and much smaller, church for the Maya, San Francisco de Asís, is actively used. A small community museum preserves art pieces from these churches. Also in town is a large cenote, Yokdzonot, for snorkeling and bathing, which was used by Mayan and Spanish troops during the war.

Ten kilometers from Sacalaca is the town of Huay Max, also shaped by the Caste War. Here a woman-led tourism cooperative, Yuumtsil Ka’ax, provides demonstrations to visitors about native foods (pumpkin, achiote, chilies, and several types of corn) and embroidery. In addition to providing a traditional meal, they guide visitors around sites of interest, including a medicinal garden, a community museum, and the colonial-era La Inmaculada Concepcíon church.

An hour drive south of Tihosuco is the once stronghold of the Cruzo’ob known as Chan Santa Cruz (Small Holy Cross, present day Felipe Carrillo Puerto). Passed over by most guidebooks, this small waystation holds several Cruzo’ob sites. Start at the Iglesia de la Santa Cruz (Church of the Holy Cross), which served as the Cruzo’ob’s main religious center of Balam Na (House of the Jaguar Priest). No plaques or markers attest to this plainly adorned building’s singularity: it was built by white slaves.

Across the inlaid brick plaza from the church is the Casa de la Cultura Maya. This building, with an arched walkway outside, was the one-time home of Mayan General Venancio Puc and later served as a base for successive Cruzo’ob governments, as well as a school for their children, where captive whites served as teachers. Also in the building complex is the Museo Maya Santa Cruz Xbáalam Naj, which houses some Caste War artifacts.

The seeming fountain in front of the building, Pila de los Azotes, is actually where locals who committed transgressions were punished under the rule of Mayan general Francisco May Pech. At the end of the Caste War in the early 20th century, he took over as the ruler of this semi-independent region. With an influx of settlers from other Mexican states, he had this structure built in order to punish those who committed infractions. For the crime of adultery, the punishment is said to have been 50 strikes.

The most famous of all Cruzo’ob buildings is a few kilometers away. Known as the Sanctuario de la Cruz Parlante (Sanctuary of the Talking Cross), this site honors the cenote where the Cruzo’ob developed a cult to a talking cross. Services are still held. Visitors are welcome, though they are asked to comply with the posted rules, such as removing their shoes at the sanctuary.

Due the guerrilla war style of the Caste war, few battle sites remain. However, just outside Valladolid, the San Bernadino de Siena Convent—the second largest Franciscan convent in the Yucatan—displays in its small museum the rifles and arms thrown into the convent’s cenote by fleeing Yucateco soldiers prior to their abandonment of the town during the Caste war.

Valladolid’s Palacio Municipal (Municipal Palace) has several murals of Yucatan history painted by Yucatecan Manuel Lizama, including one of the Caste War.

About 50 kilometers south is Tepich, the first village to be decimated by the Caste War. Mayan rebels first attacked the Iglesia de San José de Tepich. They then killed all the white and mestizo residents in retribution for the murder of Manuel Antonio Ay. In the adjacent cemetery Mayan rebel leader Cicilio Chi is buried. His grave is easy to spot as it is the only one in the cemetery! Chi’s former house is nearby.

A plaque at the base of the statue reads (in translation): “On the morning of July 30, 1847, Cecilio Chi and his people entered Tepich, executing the population of Spanish origin and burning homes, inaugurating with this act the war for the liberation of the Mayan people and turning Tepich into one of the centers of this great movement.”

Due to the relative lack of attention paid to Caste War history, only a few tour companies offer day tours. They include Playa del Carmen Tours, which has a day-long outing to several sites, starting from Valladolid. Undoubtedly, as more interest in this history grows, additional tours and experiences will be developed. The Tourist Promotion Council of Quintana Roo has created a colorful handout of many of the sites listed in this article.

Beyond their historical significance, a visit to these areas provides an opportunity to experience Mayan communities outside of the main tourist centers. Additionally, as these projects are organized and led by local Maya, their communities are the prime beneficiaries.

Clearly, this Caste War route is one that should not be cast aside!

Related posts on MexConnect

- The cuisine of the Yucatan: a gastronomical tour of the Maya heartland

- Instituto Cientifico de Na Bolom: a magical place in Chiapas for Maya studies

- Mexico’s Lincoln: The ecstasy and agony of Benito Juárez