A great deal of Oaxaca’s charm is the appearance of a timeless culture, even in the face of sprawling modernization. Its strong handcraft tradition reinforces this notion, and at first glance, it looks like all is done just like it was a hundred years ago. But there has been important innovation, with a number of women leading the way.

The innovation has been a shift from purely utilitarian items to more decorative ones. This started around the mid-20thcentury, when the state’s tourism industry took off. The creation of new ceramic forms would be important no matter who was behind it, but it is even more fascinating when you take into consideration the expectations for women in traditional rural families, especially 60+ years ago.

Women of those past generations were not raised to think of themselves as individuals to “find their own way in the world.” Their identities were that of their families, first with their parents, then with their husbands and children. Any kind of work they did was to support the family. Girls started working at a very early age, not only undertaking household chores but as part of family businesses as well. For ceramic families this means that most girls had their hands in clay before they were even 10 years old.

Girls married early—by age 18 and sometimes as early as 14/15—with their own children coming soon thereafter. Their worlds were limited to their homes and hometowns, with occasional trips to a larger town or city for selling and shopping. In the 21st century, such expectations have become less absolute, especially for those who live in less-isolated areas. But the more rural the area, the less life has changed.

With this in mind, the achievements of women like Doña Rosa, Teodora Blanco Nuñez and Josefina Aguilar are extremely important because they took advantage of what their lives had to offer and then reached beyond its confines. Their generations and those that followed have established new pottery forms with important economic and cultural benefits. Their successes have also meant a change in cultural and power structures among men and women in these communities.

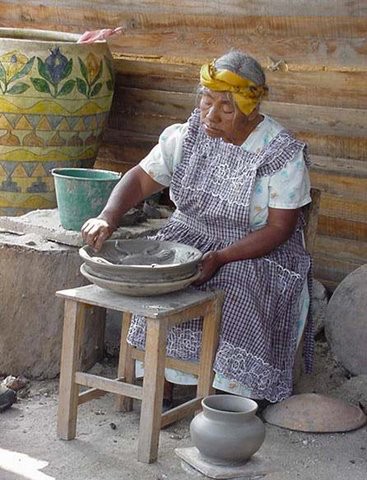

The two main types of decorative work they developed have been figurines, especially those of rural women and their lives, and decorative versions of pots, plates, jars, and other utilitarian items. The new pieces have conserved most of the old techniques, forms and decorative motifs, but have taken them to another level. Pieces are molded by hand without a potters’ wheel, using few, if any, molds. Colors are applied with clay slips or ground minerals; these and the clay base are all found locally. Most pieces are still fired with wood, in brick or pit kilns. Sometimes, large, or complicated pieces are fired in gas-powered kilns.

I do not mean to say that these women and their families have coordinated their efforts to change Oaxacan pottery. It is rare for artisan families to share techniques and designs. However, as soon as someone has success with an innovation, others immediately copy it, with real artisans reworking the innovation in their own way.

The following women have been chosen because all started out by making traditional utilitarian wares as children in their hometowns in the central valleys of Oaxaca. All saw the possibilities that tourism presented for their crafts and had the talent to create new and exceptionally fine work.

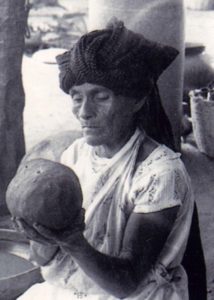

The legacy of Doña Rosa

The first of these women is Rosa Real Mateo de Nieto, known simply as Doña Rosa. Born in the early 20th century, she learned how to make the barro negro (black clay) pottery of San Bartolo Coyotepec. This pottery is distinct because of the clay mined near the town, which originally was used for utilitarian objects, especially storage containers for mezcal and other liquids. The clay was fired to a matte gray, but, in the 1950s, Doña Rosa found that if she rubbed clay surfaces with a smooth stone (a technique called burnishing), the fired piece came out a shiny black instead of a dull gray. However, water and other liquids would seep through the pottery.

Such pieces lost their original purpose, but their captivating look made them a natural for decorative versions of such wares, the range of which expanded over time into all kinds of decorative objects, from plates and figures to lamp bases and more. Her work was a success in the tourist and collectors’ markets, making her workshop a destination for major collectors and even US president Jimmy Carter.

The maestra died in 1980, but not before the entire town took notice and began producing their own shiny black pottery items. A number of families, such as the Pedros, have also become famous and have even used barro negro in murals and other art forms. Today, when you enter San Bartolo, you are immediately surrounded by stores selling such wares. Even Oaxaca State museum of popular art, MEAPO, is located here instead of the city of Oaxaca.

Doña Rosa’s family still makes the pottery the traditional way, on the same property where the maestra lived, a couple of blocks from the main square (where almost all the other workshops and stores are). Only a sign on the main road indicates where the workshop is.

+ + +

Another important pottery town in this region is Santa María Atzompa, just to the northwest of the city of Oaxaca. The area has been a pottery center for millennia, with pottery from there found at the Monte Alban archeological site. Its most traditional pottery is a green glaze cookware that developed in the colonial period and continues to be important. However, it is also home to several innovative women potters, each with distinctive styles.

Dolores Porras

Dolores Porras began working in clay at age 13 making cazuelas (similar to casseroles) and other cookware. She married at age 18 and raised nine children while making pottery six days a week. She worked with her husband until his death in 2002. She molded everything, and he was in charge of firing and selling. This means that she was the innovator—with one exception. The couple jointly developed a two-step firing process to allow for the creation of multiple colors.

One unusual aspect of Porras’s career was that she worked for a time with Teodora Blanco (see below). As was a common practice at the time, Blanco signed a number of Porras’s pieces as her own. Porras learned from Blanco before going her own way. While Porras does make some highly decorated female figures (like those Blanco made famous), it is not the focus of her work. Her innovation has been to decorate otherwise utilitarian pieces in distinctive ways, such as adding animal feet to flowerpots and painting or molding faces onto plates. The motifs that appear on her pieces also include various flowers, mermaids, iguanas, fish, and birds. These motifs may be painted and/or molded onto the main body.

Eventually, her work caught the attention of noted folk art promoter, Roberto Donis, who put in an order for 20 of her pots. Her old employer, Teodora Blanco, then followed, buying planters with turtle feet to resell. In 1980, Porras’s work started to be shown in museums in Mexico and the United States. The Hotel Las Golondrinas in the historic center of Oaxaca has a significant collection of her work, which appears in a 2010 documentary created by artist and university ceramics professor Michael Peed.

Teodora Blanco Nuñez

Teodora Blanco Nuñez began working Atzompa’s green glazed pottery working like her mother and grandmother did. However, her work stood out early for its decorative details in the markets of Oaxaca city. In the 1970s, it caught the attention of a foreign tourist, who became her patron and encouraged her to experiment.

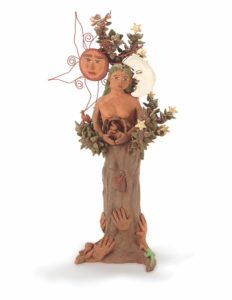

This allowed Blanco to move on from single-color glazed pottery to that using the natural colors of the local clay around Santa Maria Atzompa, in particular beige with reddish-orange accents. Blanco eventually became famous for the creation of female figurines depicting rural life, which she called muñecas (dolls). These figurines host rich decorative details made with bits of clay formed into flowers and other patterns pressed onto the main body. She also developed animal figures doing human activities, such as playing a musical instrument. Her work came to the attention of major folk-art collectors, including Nelson Rockefeller, and won numerous Mexican and international awards. Her family has since taken over, continuing the concepts she created, and adding their own touches.

Angélica Delfina Vásquez Cruz

Arden Rothstein of Friends of Oaxacan Folk Art calls Angélica Delfina Vásquez Cruz a “deeply spiritual and reflective woman whose creative work and philosophy are inspiring.”

She learned how to make toys and utilitarian wares from her parents, who had ventured into some more decorative work. However, Angelica’s decorating ideas included the faces and hands of witches, gnomes, and other creatures in children’s stories that parents told to get them to behave. Her parents did not like this particular style, convinced it would never sell.

She married at age 18, and quickly had four children. Unfortunately, she was abandoned and forced to live with her in-laws, fighting an uphill battle to be credited for the work she did. These experiences made her a staunch supporter of women’s rights. She has created works that reflect the struggles of women, especially those who go against convention or assert themselves.

On the surface, much of her work appears much like the other two-tone, beige and orange work that dominates decorative pottery here. You need to look closer at her more complicated pieces to see elements that generally do not appear in the work of others. Among the virgins, angels, animals and flowers that appear fairly universally, you will also find occasional gnomes, witches and fantastic creatures called naguals, along with skeletons and images of people from Mexico’s history. She is also an ardent feminist, so you will also find pieces that talk about women’s struggles of being a mother, wife, and artist. She has made large and extremely complicated pieces, including altars and scenes, which can run up to 25,000 pesos because they require months of work.

Museums in the United States, Mexico, and Europe have invited her to exhibit, and she has been recognized by the Banamex Foundation as one of its Grand Masters of Mexican Folk Art.

+ + +

The domination of female figures continues to the south of the city of Oaxaca to Ocotlán de Morelos. Although an important regional handcraft and art center, its center has not yet been overrun with tourists and tourism infrastructure. However, ask anyone here where the houses of Josefina and Guillermina Aguilar are and you will immediately be steered toward a block near the Hotel Real de Ocotlán.

Josefina and Guillermina Aguilar

They are two of four sisters who work in pottery. All began with their parents making angels and candleholders for altars and religious events. Their mother, Isaura, had the idea of making female figurines depicting traditional life, but she died in 1969 at only 44 years of age. It fell on Josefina to take her mother’s idea, expand it to all kinds of figures, and make them famous. Her success brought the others into the work, with Josefina and Guillermina the most recognized.

Generations later, and it is a family tradition. Every generation participates, including their spouses as they come into the fold. Although men are involved in production, women still dominate thematically and in design. The entire family’s work has been collected by many cultural institutions and serious private collectors. It is some of the most artistic of the ceramic figurines of Oaxaca’s Central Valleys as they not only depict basic aspects of traditional rural life, many also make subtle, and not-so-subtle, statements promoting traditional values. Body types vary, along with depictions of more modern life now. Perhaps most importantly, faces show a wide range of expression.

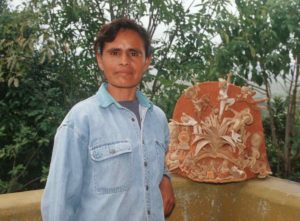

Sara Ernestina García Mendoza

One honorable mention here is the promising work of Sara Ernestina García Mendoza of San Antonino Castillo Velasco. Garcia comes from a well-known ceramicist family, but her work has stood out with the creation of hybrid woman-plant figures. She and the family are heavily attached to the earth from which they get their clay, providing a strong philosophical base for the figures. Although young, she has already been recognized with the National Ceramics Prize in 2019 in Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, and her work is strongly promoted by the Friends of Oaxacan Folk Art organization in New York.

Traditional Oaxacan pottery developed to meet basic needs: storage, cooking, and the like. Any decorative aspects were secondary. The quality of the clay and millennia of experience made towns like San Bartolo Coyotepec, Santa Maria Atzompa and Ocotlán de Morelos important pottery producing towns. Clay is in the blood. The rise of tourism, however, has allowed for a level of creativity that was probably never possible before.

Tourism and collecting provide the economic incentive, but it is these women’s own drive, creativity and ability that takes their world around them and interprets it into forms that speak to those outside. Despite the restrictions that traditional life can put on women, these creators found a voice through their clay to rise above the circumstances into which they were born… while still taking care of children and other family duties. Because of this, innovative pottery in central Oaxaca is heavily feminine, whether or not men take part in its production. These women not only benefited their families, but also their communities as well. While the preservation of traditional utilitarian wares is important, “dolls” and other collectives serve to maintain the dominance of these communities for decades, if not centuries, to come.

- Special thanks to Arden Rothstein and Friends of Oaxacan Folk Art for their help.

Related MexConnect articles

- Women potters of San Marcos Tlapazola, Oaxaca (Alvin Starkman)

- Mexican Folk Art from Oaxacan Artist Families (review of book by Arden Aibel and Anya Leah Rothstein)

- Mexico’s Mezcal Monkey: collectible ceramic folk art from Oaxaca (Alvin Starkman)

- Did you know? Oaxaca is the most culturally diverse state in Mexico (Tony Burton)