Arts of Mexico

Mexico is a country of marked contrast – raw and vital in its energy, still and timeless in its majesty. The non-hurried pace of its people belies a pulsating life force so powerful in its expression that tomorrow is swept up in today, and the moment is all that exists. To fully understand the arts of Mexico, one has to gain a sense of the overwhelming power of the landscape, the stoic endurance of the people, and the visceral connection of the people to their history and land.

The extreme contrasts in its geography and the unpredictability of its geological inheritance give a sense of urgency to the country. Vast, silent deserts give way to the suffocating vegetation of rain soaked jungles. Temperate valleys pulsate between drought and deluge. Volcanic mountains that stretch the length of the country lie semi-dormant and restless. Earthquakes rise up at will out of the bowels of the earth through the myriad of fault lines that zigzag throughout the country.

Within the borders of this majestic but unpredictable country, the relentless cycle of birth, death, and re-birth is apparent everywhere – in the crumbling buildings in constant need of repair, in the narrow streets, muddy or dusty depending on the season, in the rapid flowering and decay of plant life and the high birth and death rate of all animal life. In Mexico, nature moves through its cycles, unapologetic and in plain view – in constant change, always the same.

Here, the promise of death breathes life into every second and defines the future as no more than an accumulation of present moments. Today is all there is, all one can be sure of. Tomorrow, “mañana” is a dream that never comes. The constant reminder of the ephemeral nature of one’s small existence set against nature’s relentless and impersonal renewal has forged in the psyche of the people a sense of immediacy that has produced a body of artwork that is unique to this culture.

This immediacy explains the tactile and sensual nature of Mexican art where vibrant color saturates the canvas of its painters and enriches the dye pots of its weavers, and where stone is carved or arranged in such intricate patterns that its very complexity creates a sense of color. Even the stark, black and white prints of the 20th century print maker, Posada, have the vibrancy of color cut into the raw energy of their lines.

The need to soak up life with death nipping at the heels has fed the sensibilities of the Mexican people since pre-Columbian times. (To this day it is expressed in songs and folk art.) The old indigenous gods, still alive in the arts and fiestas, were created as a buffer between the people and nature’s relentless pursuit against their frailty. Their art was the touchstone that connected them to the gods. It permitted them to carry their finite presence into a limitless future where they could not go – thus making them eternal and god-like, a partner in the cosmos and stronger for it. The powerful connection between god and art is responsible for the richly varied body of work Cortes found when he came to plunder the people.

BEFORE CORTES

We know little about pre-classical Mexico, but the little we do know indicates that like all early agricultural societies, time was deified. However, unlike other cultures, for the early inhabitants of Mexico, time was not an abstract entity. It was a palpable thing in relentless movement from birth to death to regeneration over which they had no control. In their need to understand and fasten time, they invented a religion of many gods, and they carved the faces of their gods in stone. In those early stone faces are reflected the equilibrium of life and death, movement and immobility. Art served their religion in that only through their artwork could the dual nature of existence – the ebb and flow that we call life – be resolved.

Towards the end of the pre-classical period an early people known as the Olmecs had brought the connection between religion and art to a zenith. They showed an exceptional technical mastery of their craft as evidenced in the stelae, sarcophagi, alters, and columns that they left behind. Archeological digs have uncovered figures representing a gamut of shapes from hunchbacks and dwarfs to obese children. Also represented are images of animal masks imposed on human face, where realism and abstraction are merged into a seamless drama.

However, it’s the expressiveness of the work that raises these objects to the realm of art. In the colossal, nine-foot stone heads that they left behind, the subtlety of the carvings is extraordinary. As light passes across the figures, the faces change expression from smiles to hard impassive masks. For the Olmecs, everything was concentrated in the face where they were able to capture the presence of time on the planes and in the expression. The sculptors united an immobility with a changing mobility, and in so doing expressed the contradictory aspects of the cosmos as they saw it

In time, the Toltecs whose name in Nahual means “craftsman or architect,” replaced the Olmecs. Architecture and sculpture flourished under their hands. They are said to have built the Pyramid of Cuicuilco, the oldest structure found on this continent, about 2,500 years ago. It stands embedded in a vast black sea of basalt in the Pedregal section of Mexico City. Before the volcanic eruption of Mt. Ajusco denuded its walls, it was covered with stucco and painted in bright colors. The site was abandoned after the eruption, but Cuicuilco stands as a silent witness to the skill of the people who built it.

The Teotihuacanos followed the Toltecs. They built the awesome pyramids of Teotihuacan before disappearing forever. The sun and moon pyramids of Teotihuacan are architectural marvels whose builders understood the concept that ”form follows function” (a concept also followed at Cuicuilco) long before the 20th century. In the handling of mass and the treatment of space, they were masters. The illusion of height was their main concern, and many architectural tricks were used to enhance this effect. Even the stairways were built with this in mind. Priests and processions climbing upward would appear to disappear into the sky.

The Pyramid of the Sun held beautifully executed, powerful sculpture carved out of stone. Its walls were graced with panels in low relief that could only have been done by the most skilled hands. Subterranean chambers contained exquisite frescos in geometric patterns. Across the street from the Pyramid of the Sun, in the temple of agriculture, frescos depicted fruit and flowers being offered to the gods. The diversity in style and creative expression was remarkable.

As with the Olmecs, it is clear from this early architecture that religion and the arts were inseparable, each feeding and giving energy to the other, both fully integrated into the lives of the people. This appears to have been true of all the peoples of Mesoamerica who populated the land before the coming of the conquistadors. Styles may have differed to some degree from place to place, but it all held together in a surprisingly homogenous whole. A shared vision of the universe contributed to a continuity that survived the building, destruction, and rebuilding of civilizations.

The supreme god, Ometeotl, Lord of Duality, who alone could make “oneness” was a belief held by the majority of people who inhabited this country. This dual divinity was the creator of all beings and all things but also the Lord and Mistress of Death. However, Ometeotl was more than a god, it was a concept – time in perpetual motion bringing death and sparking life in an endless dance – that needed a resolution.

The desire to hold time still created the need for architecture to serve as a sanctuary. It also created the need for an expression where duality could be resolved by sharing the power of the supreme god, Ometeotl, who alone could make “oneness”. Sculpture was the ideal medium as witnessed in the many clay figures with two heads or the half skull, half laughing faces, or the double noses or mouths on much of the art work. But all the arts flourished as is evidenced by the carvings and craft work left behind.

Time makes and remakes us, but every work of art is a form animated by the will to survive time and its erosions. One has only to look to Mitla with its fretted geometric decoration, or the sinuously carved serpents of Xochicalco, or the massive basalt figures, 15 feet high, atop the pyramid of Tula to see how strong this concept was in the will of a people whose religion, art, and daily life were so intricately entwined.

One of the greatest finds attesting to the high artistic development of the indigenous people was in a tomb uncovered in the valley of Oaxaca – the work attributed to the Mixtecans and probably buried not long before The Conquest. When this tomb was first opened, the archeologists were stunned by the presence of a large bowl made of rock crystal, an extraordinarily difficult material to carve even today with modern tools. The floor was littered with craftwork and jewels of unmatched beauty and workmanship. It took a week working 14 hours a day to gather and catalogue the find.

Another site in the area gave up a gold diadem with plumes of beaten gold, gold breast plates, a gold collar with a fringe of gold bells, a mask of intricately carved gold, gold-beaded necklaces – each bead a carved head, gold ear pendants, rings, and bracelets, and lip ornaments of gold and jade. Also found were beads of jet and amber, obsidian ear studs and knives, and objects carved from the bones of deer and jaguar cut in high relief and as exquisite as anything done in ivory from China or Japan.

There were vases and urns of translucent white onyx with intricately carved inscriptions, delicate ornaments of gold, amazingly beautiful in design and executed with an artistry that would be equal to Benvenuto Cellini’s, the great Italian jeweler of the Renaissance. The collection can be seen at the State Museum of Oaxaca where a large room is devoted to their display.

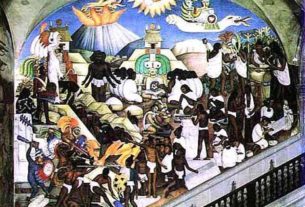

Mural paintings proliferated in the early buildings of Mesoamerica – fragments still visible in whatever has remained of pre-Columbian architecture. Under the crumbling plaster of early churches built upon old temple sites are remnants of beautiful pre-Columbian frescoes, much of the brilliant color still in evidence. In the early twentieth century, when the Mexican people finally broke free of outside interference in their daily lives, mural painting became the first conscious and deliberate answer to European art.

The last group of indigenous people to hold reign over Mexico was the Aztecs. Tenochtitlan, which is now Mexico City, was their capital. Quetzalcoatl, the Toltec god of civilization and learning, was adopted by them, as he was by each new wave of conquerors, and ruled alongside the great war god, Huitzilopotchtli. Aztec reign came to be known as the golden age of Anahuac, the name of the valley in which Tenochtitlan resided.

When Cortés invaded the valley, two peoples – the peaceful Texcocans and the war-like Aztecs – inhabited opposite shores of Texcoco Lake, the largest of the many lakes that dotted the Anahuac region. Texcoco, known as the artistic and intellectual center, was famous for its temples and palaces. Its homes were set along canals, many of them with terraced gardens adorned with statues. Pools, waterfalls, and orchards enhanced the gentle rhythm of the peaceful city. Music, poetry, and painting flourished.

Tenochtitlan, capital of the more predatory Aztecs, was the military and commercial center, its paved streets teeming with people. It was an island city joined to the mainland by great stone and cement causeways. Drawbridges protected the city and lighthouses guided fishermen home. Palaces of stone lined the avenues, their terraced roofs filled with flowers. Canals, alive with canoes, intersected the streets and the bridges which crossed them. The magic and majesty of the city is said to have rivaled Venice at its height.

The halls of the last Aztec ruler, Moctezuma, were filled with the creative ingenuity of his subjects. Gorgeous tapestries in multicolored delicate feather work hung on the walls. Furniture was decorated with inlaid woods, and benches were elaborately carved from single pieces of wood.

When Moctezuma got word of Cortés’s coming, he believed the Spaniard was Quetzacoatl. According to legend, Quetzacoatl, the great god of peace, went into exile but was to return one day. Moctezuma believed that Cortés was the god returning to punish him for his war-like ways. He offered Cortés a part of his treasures in an attempt to bribe him away from the land. The gift was mind-boggling – a solid golden sun and silver moon the size of cartwheels, a turquoise mask with a crown of feathers, cloaks of feather work, birds and animals of gold and silver, and a helmet filled with gold.

This small token given out of fear from the still mighty chieftain did little more than whet the appetite of Cortés. He lost no time in adding to the booty. In 1519 a treasure trove of priceless art objects was shipped to Spain and exhibited. Europeans were stunned. The German artist, Albrecht Durer, was moved to write “…In all my life I have never seen anything that has so delighted my heart as did these objects; for there I saw strange works of art and have been left amazed by the subtle inventiveness of the men of far off lands.”

Cortés was determined to take Tenochtitlan. For three months his men besieged the city but couldn’t advance. In frustration, Cortes ordered the men to destroy the houses one by one, the rubble and debris to be used as fill to clog the canals. Water was converted to dry land for the movement of the Cavalry.

Cortés had called Tenochtitlan the most beautiful city in the world. Nothing like it existed in Europe. That didn’t stop him from leveling it to the ground. In 1521 the great valley of Anahuac was finally taken, all traces of its splendor deliberately annihilated. No civilization has ever again reached such a high level of integration between the people and its arts, and the splendor of Tenochtitlan has never again been repeated.