Arts of Mexico

“While we are alive, we cannot escape from

masks or names. We are inseparable from

our fictions – our features.”

Octavio Paz

When I arrived in Mexico City in 1967, the first unexpected delight to catch my attention was the incredible array of masks that popped up everywhere in the city. Some stared at me through blank, hollow eyes from inside shop windows. Others were carelessly heaped on one another in outdoor market places or preciously displayed on walls in up-market government craft stores. I was stunned by the variety of material, the breadth of subject matter, and the extraordinary imagination that went into their making. It was evident that the masks of Mexico were not just collector’s items or tourist trophies but a vital, living part of the Mexican heritage.

My first purchase was a small carved deer’s head that I took with me from country to country over the next 30 years, and which mysteriously got lost on its way back to Mexico. And then maybe not so mysterious, as masks represent a shift in reality, and perhaps I no longer needed it returning to a country steeped in so many realities, its layers, like geographic sediment, often mixing with the one above or below and covering as many eons.

Though every culture has masks as part of its cultural heritage, no country has such a variety of representation from its different regions and, as far as I know, few have masks so well integrated into the history and culture of its people.

The earliest evidence of mask making in the Americas is a fossil vertebra of a now extinct llama that was found in Tequixquiac in Mexico. It was carved sometime between 12,000 and 10,000 BC and represents the head of a coyote. No other evidence was found until about 1200 BC when distinct styles of mask making in clay and stone began to emerge. At the Kabah site, just 18 kilometers from Uxmal, the Palace of Masks (7 -10 AD), is just starting to be restored. It’s façade is covered with hundreds of masks depicting the rain god, Chac.

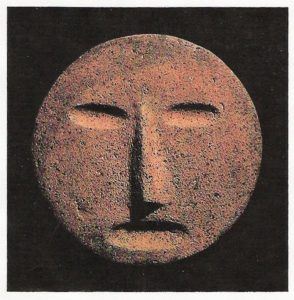

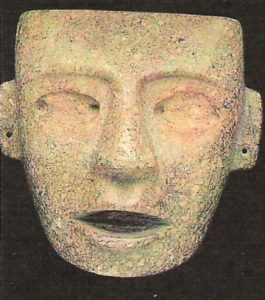

Three distinctive styles developed in pre-Hispanic times. One was from the Mexcala region in what is now northeast Guerrero. These masks are flattened with minimal features and perforated in the middle of the forehead for suspension. The masks have no openings for eyes, and it is assumed they were used to cover the faces of the dead. The Mezcala style is devoid of all the expressive qualities of central Mexican or Olmec masks but seems to have exerted a strong influence in the later stone masks from Teotihuacan (300 – 650 AD).

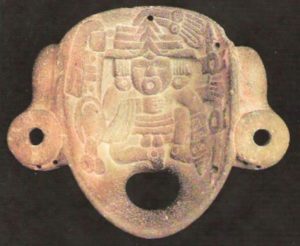

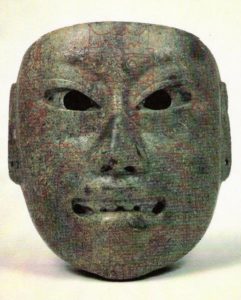

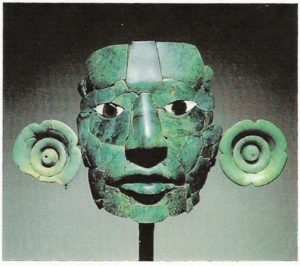

The Olmecs had their own style and, unlike the Aztecs of central Mexico, used jade, serpentine, quartzite and onyx in the production of their masks. Human images outnumbered deities and they did a fair share of dragons, were-jaguars, and bird monsters. These more naturalistic masks, particularly from around what is now the state of Vera Cruz, show that the profiles of deities were carved and outlined in cinnabar.

In the Olmec masks, human identity is rarely submerged by the animal or deity represented by the mask.

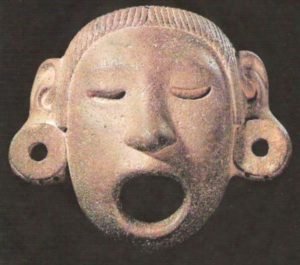

The last group of masks from the Valley of Mexico, most of them ceramic, shows that here deities were favored. A common mask they made had a rounded, expressionless face with circular eyes and open mouth. Its smooth surface representing flayed skin, associates it with the god Xipe Totec. The Aztecs used this god in the spring festivals for agricultural renewal. Another god mask that was fairly common had grotesque features with deep sunken eyes and wrinkled skin and is thought to be the fire god, Huehueteotl. They also did a version of the Olmec were-jaguar or dragon with feline characteristics and dragon teeth. Masks representing multi-leveled reality with half living and half fleshless skulls or half man and half animal are prevalent here. In Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec empire, archeologists have found masks imbedded in the construction of the Templo Mayor (Great Temple), probably put there as offerings to the gods.

The largest number of masks from the late pre-classic period came from the Valley of Mexico and Olmec sites. However, outside these areas, in isolated parts of the country regional styles proliferated.

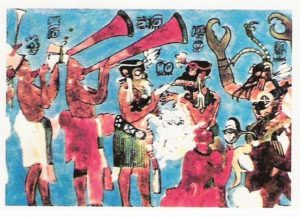

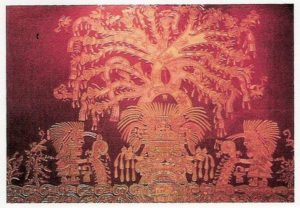

From the remains of pre-Columbian murals and codices, it is evident that in the pre-Hispanic world masks were an integral part of life bringing together the secular and religious into a seamless whole. The surviving murals at Teotihuacan illustrate gods or priests wearing elaborate feather headdresses mounted over masks. Even those who were to be sacrificed to the gods wore masks. And in the Bonampak murals entertainers and musicians wear fanciful masks depicting everything from animals to sea creatures. Unfortunately those masks weren’t made of materials that have survived.

The Codex Borbonicus depicts the New Fire Ceremony where women and children are locked in their homes and protected by masks to prevent malevolent spirits from transforming them into animals. In fact, masks were so important to the Aztec civilization that the Codex Mendoza and the Matricula de Tributos list the towns that supplied the materials for their making or the masks themselves – objects that were paid as tribute to the Aztec state.

Even the elaborate dress of the warriors incorporated masks. The two principal military orders – the Eagle and Jaguar knights – wore costumes with realistic animal headdresses, representing the animal in whose order they belonged. Their attire probably helped to instill in them the traits of these animals with which they identified and with whom they may have believed they shared a personal soul.

A significant reason for such emphasis on multiple appearances may be due to the pre-Hispanic perception of physical boundaries. The Aztecs believed that a person was not one of a completely and freely acting agent where boundaries correspond to those of the physical body as is thought of in the West. They believed a powerful relationship existed between the “person” and animals, plants, and natural and supernatural phenomena. (Among Mexicans today, there are those who believe each man and woman shares a destiny with an animal counterpart, and whatever happens to one will happen to the other whether it is illness, hunger, injury or death. This soul companion is called a “Tona”.)

Before the conversion to Christianity, every child depending on the day of birth was paired with a particular animal, plant or natural phenomena with which he or she shared a personal soul. The plant or animal was an alter ego whose fate was linked with its human counterpart. People were believed to be able to transform into their counterparts, particularly high ranking priests and rulers. The masks alluded to the co-existence of multiple human, natural, and supernatural qualities within the same body, in effect making the mask a medium for creation and revelation as opposed to concealment.

The dead were buried with masks, or masks were attached to mortuary bundles in regions where cremation was practiced. High ranking priests and rulers were wrapped in fine fabrics and masks were placed over their faces before cremation. After, bundles were made representing the deceased. These bundles were dressed in finer clothes and a more elaborate mask The masks represented the deities with whom they were most closely affiliated. One king had five layers of costumes complete with masks to represent each of his different roles.

Because of the metaphysical power connected with masks, their ownership had strong political implications. The possession of the enemies’ skin or skull signified the expropriation of the group’s supernatural affiliations which would leave them defenseless. Because of this belief, the enemy’s skin was often an element used in mask making.

The primary purpose of the pre-Columbian masks was neither to efface or reveal, but to serve as vessels or repositories in which powerful energy was stored. As a result, the masks sometimes became sacred religious objects in themselves. They symbolized the Indian’s belief in the coexistence of the many facets of the human psyche and were a way of depicting multi-level existence.

The role masks played in the life of the indigenous people changed after the conquest, and yet in many ways it hasn’t. Next month I’d like to go into how the masks evolved, creatively and socially, after the coming of Cortes.