Did You Know…?

The Quetzal Dance is one of the most colorful folkloric dances anywhere in the country. It is also thought to be one of the most ancient. Both the dance and the spectacular headdresses worn by those taking part are thought to pre-date the Conquest, perhaps by hundreds of years.

The headdresses represent the extravagant colors of the quetzal bird, a sacred bird of the Maya. The resplendent quetzal, as it is called by ornithologists, sports long green tail plumes that grow up to four feet (1.2 meters) in length. These feathers were highly prized by many ancient peoples, especially the Aztecs of central Mexico, who demanded quetzal feathers from some villages as part of their tribute payments.

Today, the bird can be seen in the wild only in the forested highlands extending from the state of Chiapas, in the extreme south of Mexico, to the north of Costa Rica. This region includes Guatemala, where the quetzal features prominently on national symbols and gives its name to the unit of currency. There are not many quetzal birds left today, with most hopes for the bird’s long term survival pinned on the Quetzal Reserve in Guatemala, where a large area of cloud forest has been set aside for research and conservation efforts.

In pre-Conquest times, it was considered a serious offence to kill a quetzal, so catching a specimen to remove its tail feathers developed into an art form. Oral testimonies suggest that quetzales were trapped where they landed to eat or drink, and that great precautions were taken to avoid touching the desired feathers with the hands. Only tail feathers were taken. At some point, it seems to have occurred to some budding entrepreneur that it might be profitable to keep a few of the birds in captivity, thereby guaranteeing a steady supply of feathers. The feathers would eventually find their way to the suppliers of the elaborate headdresses of upper class citizens in far-away Tenochtitlan, the capital of the powerful Aztec Empire. Perhaps the finest of all these headdresses ( penachos) was the Feather Crown belonging to Emperor Moctezuma (1466-1520) that now resides in a museum in Vienna, Austria. It has been the subject of repeated requests for repatriation made by Mexico’s cultural authorities and indigenous groups. A replica is displayed in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City.

The quetzal’s significance was such that it gave rise to the important Meso-American deity “Quetzalcoatl”, the feathered serpent.

Described by many ornithologists as “the most spectacular bird in the New World”, the resplendent quetzal ( Pharomachrus mocinno) was first reported in the scientific literature in the nineteenth century. Not long after the first specimens arrived in Europe, milliners there began a craze for the feathers, leading to widespread hunting of quetzales, to collect plumes for export. As a scientific curiosity, modern electron microscope examination of quetzal feathers, usually thought of as being highly colored, shows that they are actually a boring brown in color. However, the spots of pigment are so small that they break up sunlight into the emerald green, azure blues and shiny gold seen by birders.

Despite the fact that the only surviving quetzal habitat in Mexico is in Chiapas, the Quetzal Dance is restricted to a small area much further north: a few villages in the lowlands of the state of Veracruz and in the nearby mountains of Puebla. One of the most photogenic locations where it is still performed is the appropriately-named village of Cuetzalan (= “place of the quetzales”) in northern Puebla, a Totonac Indian settlement.

Cuetzalan is a fascinating village for lots of reasons, and hit the news headlines early in 2004 when several British cavers had to be rescued after becoming trapped by rising water deep underground. The mishap became a diplomatic incident after it emerged that the cavers were members of the British armed forces.

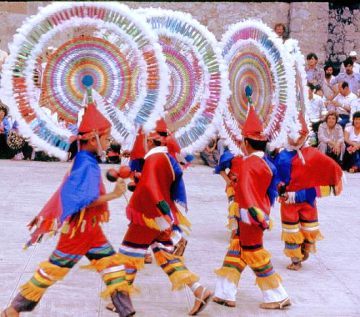

I’ve been lucky enough to see the dance on several occasions in Cuetzalan during the village’s major festivities in early October, and have to agree with Frances Toor’s description in her Treasury of Mexican Folkways that it is both “primitive and beautiful”. Toor describes the “costumes of vivid colors, red predominating” at some length, and then turns her attention to the “huge wheel, over five feet in diameter, with colored paper or silk ribbons interlaced through a network of slender reeds with a border of lovely feathers. This brilliant wheel, justly called a splendor, is attached to a conical cap on the head of the dancer, held by a ribbon or kerchief tied under the chin.” This is the spendiferous headdress of the Quetzal Dance.

Not all the splendors are five feet (1.5 meters) in diameter. As the accompanying photos show, younger participants are usually only entrusted with much smaller headdresses than their experienced elders.

The dance itself is not very elaborate, though precise execution is necessary to avoid collisions between headdresses. The dancers, usually in a group of about a dozen or so, form two ranks and then, in response to simple melodies played on a small drum ( nenetl) and reed flute ( flauta), wind around to form a series of crosses (believed to represent the cardinal points) and circles (interpreted as either the passage of stars or of the sun). The dancers carry rattles ( sonajas) and shake them to the rhythms of the dance. All the musical instruments used date back to pre-Hispanic times.

It is thought that the Quetzal Dance may have been common in this area of Puebla for many centuries before the Conquest, presumably at a time when the quetzal could still be found in the local forests. Perhaps the dance developed because the local Indians had to pay quetzal feathers as tribute to their Aztec overlords, or perhaps it was their way of apologizing to the birds for having to sacrifice some of them in the interests of meeting their tribute demand?

If you’re unable to see the Quetzal Dance in its original setting in Cuetzalan, then look for it next time you attend a performance by the Ballet Folclórico Nacional, Ballet Folclórico de Guadalajara, or any other modern troupe, all of which periodically include it in their shows.

Copyright 2004 by Tony Burton. All rights reserved.