On my last visit to Cabo San Lucas in 1997, the city had installed its second traffic light four months ago. It stands on the northwestern outskirts of town, where Mexico Hwy. 19 begins its winding journey to Todos Santos, 45 miles away. So far no one had bothered to turn it on, but I stop at the intersection anyway, just in case it winks to life and brings order to the crossroads anarchy that has reigned over this spot ever since my first visit to Cabo nine years ago.

I zigzag the rented VW bug through the one-way street patterns downtown and have no trouble finding a parking spot along Blvd. Marina. Continuing on foot along the waterfront, I find few indications that this might be the fastest-growing beach resort in Mexico, as has been claimed. Still, although it’s a relatively small town of only 25,000, no one would ever use the word “quaint” to describe Cabo San Lucas. A first-class, 330-slip marina, complete with full-service chandlery, cuts into one side of a harbor nearly surrounded with hotels and condos built in the Santa Fe style. A large shopping mall and cineplex are going in next to the marina, along with a sprinkling of new condo developments. Steady growth, yes, but hardly meteoric in this third year following the 1995 devaluation of the Mexican peso, a currency upheaval that all but killed the economy elsewhere in Mexico.

Dairy Queen, Pizza Hut, Planet Hollywood, and Hard Rock Cafe stand side by side along Blvd. Lázaro Cárdenas, a busy four-laner that comes in from the northeast and wraps around the square harbor. Interspersed among the American franchises sit older, funkier restaurant-discos like The Giggling Marlin, Cabo Wabo, and Squid Roe, where red-faced young Americans and Canadians crowd three- and four-deep at the bar to buy two-for-one margaritas made with Mexico’s cheapest tequila, then dance till 2 a.m. to the latest international hits played by English-speaking DJs.

By the time I’ve walked three or four blocks away from the marina toward the gray foothills of the Sierra de La Laguna, San Lucas’ slick facade has faded into a maze of unpaved sand lanes lined with the tortillerías, hardware shops, and markets typical of any small coastal Mexican town. Visitors on holiday almost never venture this far away from the waterfront and there’s little reason they should. None of the architecture is historic; most of it is made of concrete block.

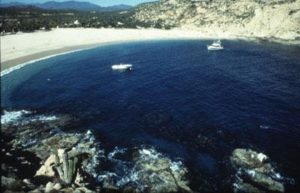

Deep Bahía San Lucas – dropping hundreds of feet into a submarine canyon less than 50 yards offshore and fed by two oceanic bodies, the Sea of Cortez to the east of Cabo San Lucas and the Pacific Ocean to the west – saves Cabo from being just another beach party town like Cancún. Yacht sailors on their way to and from other Pacific ports add a small element of sophistication to the local scene. Scuba divers are drawn to the area by thehighly favorable year-round climate, which makes Cabo the only beach resort in Mexico where both summers and winters are tolerable; the average number of days with sunshine far exceeds anything found in Florida, California, the Caribbean, or the South Pacific. Beyond the bay toward mainland Mexico lies prolific “Marlin Alley,” a strait teeming with hard-fighting billfish which challenge visiting anglers to live out their Hemingway fantasies.

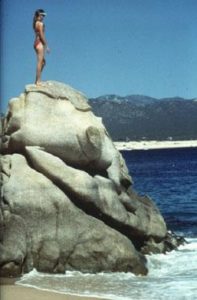

A cathedral-like cluster of granite outcroppings, carved by wind and waves into fantastic shapes, tumbles into the sea at the Cape’s southernmost point and forms the coccyx of a rocky spine that reaches northward all the way to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. The English pirates and Spanish conquistadors that battled for a foothold in 18th-century Baja California named these formations “Land’s End” or “Finisterra.” This position at the tail end of the Baja California peninsula makes it the last stop on the notorious thousand-mile transpeninsular Baja road trip, hence Cabo also acts as a road depot for Baja explorers looking for a few days or weeks of R&R before beginning the long return drive across relatively unpopulated desert landscapes.

This influx of arrivals by road, air, and sea means you never know who you’ll run into in Cabo. Sailing bums taking on supplies for a Tahiti crossing, cops on a fishing vacation, Baja road warriors, honeymoon couples, Mexico City denizens cleaning out their lead-filled lungs, rockers resting up after a continental tour, or Montana cowboys escaping the snow–they’ve all set themselves temporarily adrift in the Pacific, like the Cape itself as it inches westward from mainland Mexico.

Of course the meat and potatoes of Cabo tourism are its beaches, which fan out from the Cape to the northwest and northeast and capture the lion’s share of visiting vacationers, most of whom come from the west coast of the U.S. and Canada. Just east of the harbor entrance, Playa El Médano, a long, curving strip of sand washed by gentle shorebreaks, is lined with the most expensive hotels within the city limits. Playa Amante – more commonly known as “Lover’s Beach” – is a pristine beach preserve squeezed between the granite boulders at Land’s End and blessed with two separate beach fronts, one on the bay and one on the Pacific. Decreed a marine preserve in 1973 and accessible only by boat, this 14-square-mile patch of sea and shore is regulated with special boat lanes, boating speed limits, and restricted fishing and recreation craft areas, all under the watchful eye of Grupo Ecológico de Cabo San Lucas.

After a leisurely lunch at El Pescador, my favorite spot for fresh seafood and local color, I’m back in the car and headed northeast out of town on Mexico Hwy. 1, the Transpeninsular Highway.

The 18-mile, four-lane stretch between San José del Cabo and Cabo San Lucas provides access to 17 named beaches. Known officially as the Corredor Naútico (“Nautical Corridor”), or more commonly in English simply as “the Corridor,” this whole strip has become the focus of Cabo’s most ambitious development projects, including five major golf courses and elegant resorts such as Las Ventanas al Paraíso, Westin Regina, Melía Cabo Real, and Hotel Palmilla. As I drive the Corridor I see several newer resorts under construction and am pleased to note that the trend toward low-density, high-quality development remains the norm. Golf courses in the corridor recycle gray water to cut down on freshwater consumption, the only responsible alternative in a region of scant rainfall.

Repeat visitors or savy first-timers with adventurous spirits will find plenty of other areas beyond the coastal strip to explore, beginning with San José del Cabo at the northeastern end of the Corridor. San José represents the quieter, more traditional Mexican side of the two Cabos–known collectively as “Los Cabos” in tourist literature–and attracts those who may find San Lucas too Americanized and too youth-oriented. Century-old brick and adobe buildings, many of them proudly restored, line the main streets radiating from San José’s plaza and church. These are interspersed with Indian laurel trees, palms, and other greenery, making San José one of the most pleasant pedestrian towns in Baja’s Cape Region.

On warm evenings Mexican families sit on their porch steps or on wooden rockers brought from inside and chat for hours. In strong contrast with Cabo’s drink-dance-and-make-noise mandate, the nighttime model in San José seems to revolve round quiet, candlelit evenings at local restaurants. The place I choose to spend the night, the Tropicana Inn, turns out to be the exception that proves the rule–the bar can be noisy and it stays open late. However, the band-consisting of a saxophonist/keyboardist from New York, a young conga drummer from Cuba, and a vocalist from Mexico City-is so talented I don’t miss the lost sleep.

In the morning I’m back on the road and easing into my favorite part of the Cape loop drive – north of Los Barriles along the gently sloping eastern escarpment of the Sierra de La Laguna, Baja’s only volcanic mountain range and the recipient of more rainfall than any other Baja locale. As I begin the winding ascent into the sierra via Mexico Hwy. 1, the air temperature drops ever so slightly and the classic Baja scenery kicks in, splashing a montage of acacia greens, arroyo reds, and rocky grays across the windshield. A few modest thatched-roof cafes in the faded old mining-turned-farming towns of San Bartolo, San Antonio, and El Triunfo offer the only sustenance along the way.

Two hours or so north of San José the mountains flatten out onto a coastal plateau that gradually descends to the edge of the Sea of Cortez and to the state capital of Baja California Sur, La Paz. A city of 180,000 noted for its attractive bayside malecón (waterfront promenade) backed by swaying palms and pastel-colored buildings, La Paz offers splendid sunsets, an easygoing pace, economic meals and hotels, and a near-perfect winter climate, although it can be blazing hot in the summer since its position on the peninsula blocks southern and western breezes that cool the Pacific side. La Paz’s proximity to uncrowded beaches on the Pichilingüe Peninsula and pristine desert islands just offshore makes the city a sleeper favorite among Mexican and foreign travelers alike. The lack of a decent beach in town keeps the crowds at bay.

After a ritual meal at La Terraza, a popular and authentically Mexican outdoor cafe beneath the city’s oldest hotel, I point the hood ornament south, retracing my tracks along Mexico Hwy. 1. After 15 miles I veer southwest onto Mexico Hwy. 19 at minuscule San Pedro. Unpaved until the mid-1980s, the latter highway provides the only vehicular link with Todos Santos, another 32 miles away. It’s a pretty drive, with the northern end of the Sierra de la Laguna visible in the distance off to the left side of the highway and relatively verdant desert–some of the cacti even bear ball moss, nourished by moist Pacific air–closer in on both sides of the road. At two-hundred-year-old ranchos scattered thinly along the way, fifth- and sixth-generation bajacalifornianos still produce fresh cheeses and machaca (jerked meat), and make rustic, hand-crafted chaps, sandals, shoes, and burro saddles. Although opportunities to tour these ranches are rare, a visit provides a glimpse of the Baja California interior culture and a Spanish lifestyle that has all but disappeared elsewhere in Mexico.

Abut 15 miles south of San Pedro, I take another roadside break at La Garita, a Baja-style truck stop sheltered by a palapa roof thatched with leaves of the native Mexican fan palm that have been fastened together with strips of rawhide. The modest kitchen brews the best traditional Mexican coffee in the Cape Region, using Chiapas beans that have been roasted and ground on the spot.

A row of roadside palapa shacks selling dulces made with guava, mango, papaya, coconut, and other tropical fruits signals the northern entrance to Todos Santos. Watered by an underground spring system and thus one of the more lushly vegetated arroyo settlements in the Cape Region, Todos Santos served as a food supply center for the Spanish mission community in freshwater-poor La Paz in the early 18th century and has been continually inhabited ever since. Beneath the town’s sleepy surface and behind the century-old brick-and-plaster facades lives a small, year-round colony of expatriate artists, surfers, and organic farmers who have found this locale to be the ideal place to follow their independent pursuits. A few La Paz residents maintain homes here as temporary escapes from the Cortez coast’s intense summer heat; these are complemented by a seasonal community of California refugees from the high-stress film and media worlds who make the town their winter retreat.

Todos Santos’s growing reputation for la grande vida rests on three cultural touchstones that set the town apart from other Cape Region destinations. Like any other knowledgeable visitor I make a studied pilgrimage to each whenever I’m in town. Impressive enough to have gained the attention of Travel and Leisure and other North American publications, the Café Santa Fé on the plaza provides a quiet, very tastefully decorated space in a 150-year-old courtyard casona, surrounded by 18-inch-thick adobe walls where one can dine on Mediterranean-inspired seafood dishes prepared with fresh herbs from the Italian proprietor’s own garden.

A few blocks away stands shrine number two, the Todos Santos Inn, a restored post-colonial mansion with two impeccably furnished rooms (and two more under construction) opening onto a flagstone patio where the ex-Bostonian owner serves breakfast to his guests. Number three, the Galería de Todos Santos, occupies a separate corner of the inn and displays some of the best art produced in the Cape Region. Despite the cultural high road the community has embarked upon, this the least expensive coastal town in the Cape Region with tourist facilities.

I drive the final 47-mile leg of the loop along the Pacific coastline back to Cabo San Lucas, salivating over the many “undiscovered” surfing and swimming beaches along the way. I stop at my favorite, Playa Las Cabrillas (turnoff at Km 81). Flat and sandy, the beach is named for the plentiful seabass that can be caught from shore.

Grass-tufted dunes provide partial windscreens for beach camping, but I only stop long enough to dodge the shorebreakers and hit that perfect zone just behind the break where the sandy bottom drops away from my feet and I’m seemingly floating free of all worldly cares. Still the least developed coastal stretch in the entire Cape Region, it’s only a matter of time before this area is dotted with resorts. Housing developments are already slowly appearing along the southern end of the highway outside Cabo San Lucas. Local resistance to development–especially in the Todos Santos area–is growing, so perhaps the area farther north will remain preserved and relatively pristine.

At journey’s end I convert once again to American tourist status and belly-up to the bar at Latitude 22+ to swap travel stories with the same four-corners-of-the-world crew I was happy to abandon several days earlier. Baja’s Cape Region, I realize as I grope for descriptions, represents exactly the sum of its parts. With its desert shores embracing an oval of verdant mountains, and looped by an eminently driveable road, it dangles tantalizingly like a diamond-and-emerald pendant floating on azure seas. All in one bundle it offers the remote and the familiar, the ascetic and the indulgent, the traditional and the trendy, art and artifice, the desert and the tropical. I can’t help feeling a bit sorry for the many people who see only the airport and the beach. But the word seems to be getting out.

SIDEBAR

I’ve found navigating by car in the Cape Region to be one of the tamest driving experiences in Mexico. With a population density of only five persons per square kilometer, Baja California Sur is the nation’s most sparsely inhabited state, so traffic tends to be very light. All the usual recommendations about driving in Mexico should be heeded. Avoid driving at night because of loose livestock on the roads, and keep your speed below 65 miles an hour to anticipate highly variable road conditions.

Los Cabos International Airport, eight miles north of San José, is the best place to rent a car if you plan to explore the Cape Region on your own. Around a half dozen companies operate rental booths in the arrival area; if you book ahead, Avis International offers the best weekly rental rates.

Those with enough time can make a rewarding circular route around the Cape Region via paved highways Mexico 1 and Mexico 19. Extending a total distance of approximately 350 miles, this loop takes visitors along the lower slopes of the Sierra de la Laguna, through the sierra’s former mining towns, across the coastal plains to La Paz, and along West Cape to the former mission town of Todos Santos. The loop can be comfortably driven in two or three days but visitors with additional time would be able to stop more frequently and see more of the region. A comfortable week-long itinerary might include two nights each in Todos Santos and La Paz, coupled with three nights in either San José del Cabo or Cabo San Lucas.