Mexico Design & Style

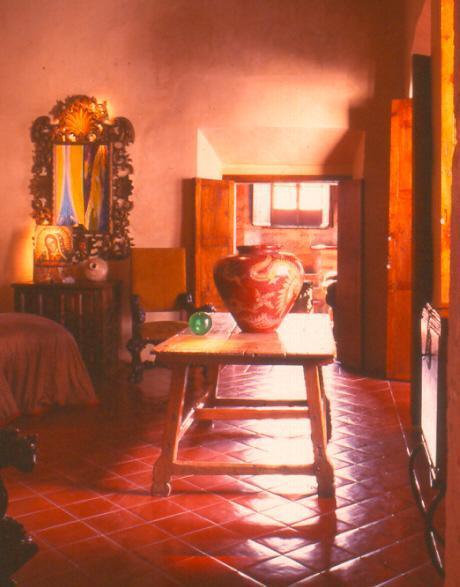

Sun-drenched colors of burnt ochre and red ignite massive walls and bring stone-chinked surface patterns to life. Antique wooden doors punctuated with hand-forged iron clavos open to reveal cool, tiled salas with lofty, wood-beamed ceilings and rustic colonial furniture. Brightly-tiled kitchens beckon with well-worn tables, glazed ceramics and utilitarian objects in stone, wood and copper. Sparsley-furnished rooms display artful devotional displays alongside family heirlooms and local folk art.

For decades, the soulful nature and character-rich details of Mexican furniture, architectural elements and handcrafted accents have captivated us with their beauty and ingenuity. From painted tables and chip-carved benches to hand-hewn corbels and stone-carved columns, Mexican design elements are like mirrors reflecting a rich cultural history and the creativity of the hands that made them.

Beginning their lives in marketplaces, ranches and workshops as the cornerstones of cultural traditions, Mexican country elements have evolved gracefully over time and evoke the rhythms of rural life from which they originated.

We have connected to the strength and imagination of these handwrought objects and have relished living with them on a daily basis. Our exploration of Mexican design and living has spanned many years and regions, including the remote mountains of Mexico and the mesquite mesas of the American Southwest.

On countless design pilgrimages we have documented the antiques in their original contexts—such as in mercados, coffee plantations, remote haciendas, artists’ studios, colonial homes and in the midst of processions at Christmas and Semana Santa. We have enjoyed researching their rural origins as well as their newfound contemporary manifestations, watching as they have been reinvented and adapted to new contexts.

First embraced in the Southwest, the Mexican design style has transcended its rural beginnings to take root in elegant ranch homes in Montana, illustrious lofts in New York, Luxe hotels and eco-conscious spas, tropical retreats and contemporary homes throughout the U.S. and Mexico.

A deep interest in the world of Mexican furnishing and its influence on contemporary home design led us to publish our first book, Mexican Country Style, which explores this expressive style on both sides of the border and offers information on identifying and preserving Mexican antiques.

A spirited mix of native Indian and Spanish influences, the Mexican design style heralds the use of natural materials, rich-hued colors and textures. Minimally-furnished interiors blend handcrafted antiques with contemporary art and furniture, creating a pared-down elegance with an intriguing mix of old and new.

Choice antiques feature hand-hewn hardwoods, pleasing proportions, original hardware, rare joinery and innovative techniques of the craftsmen. Architectural elements–old doors and gates; exposed beams, corbels and lintels; carved stone columns, moldings and doorway surrounds; stucco details, ceramic floor tiles—the true design elements that ornament a room.

Unlike traditional American antiques, which are sought for their pristine condition, Mexican antiques are coveted for their imperfections. Often self-taught, many carpenters made up for the absence of fine tools by using the natural aberrations of beautiful woods to make individual statements. In this way, knot holes become a table’s punctuation.

The complex appeal of wear marks and age include multiple layers of old paint, surfaces that have been personalized with cattle brands, candle burn marks, native repairs done with tin or rawhide straps, old nails and worn edges. The carved initials of old sweethearts or numbers commemorating significant dates are sometimes also present on country furnishings.

Doors that have withstood decades of weather—with painted surfaces faded to shades one only wishes he could duplicate, their hardware pitted and rusted and later polished by use—still maintain their strength and authority. The restoration of Mexican antiques—both native and recent—is common and in many ways adds to the value and enjoyment of the pieces.

Transporting many of these old-world treasures back to life through restoration and new adaptation has brought us great pleasure. Through our design projects, we have witnessed a new generation of homeowners and design professionals that have discovered the charms of Mexican antiques and embraced their versatility for myriad new roles in today’s interiors and gardens.

Cypress jail doors, replete with their intact hardware, have been turned horizontal to become unique console tables, old coffee mortars are new decorative vessels for fruit or firewood, and corral gates are mounted into headboards. Even storage trunks, long separated from their original wooden bases, are returned to function with custom wrought-iron bases.

DESIGN PILGRIMAGES

For centuries, the Mexican craftsman has instinctively combined beauty with function, using the materials provided by nature to create furniture, culinary vessels, architectural elements, implements and religious objects. These functional and noble elements reflect Mexico’s wildly diverse landscape and her pre-Columbian, European, and Indian influences.

Fascinating and amusing hours have been spent with innovative village craftsmen, carpinteros, farmers, antique dealers, and homeowners as we examined old relics—doors, gates, altar tables, armarios and trunks–and learned the subtleties of the local hardwoods, construction methods, hardware styles and original uses. From unique dovetail joinery on furniture and hand-wrought iron hardware, to old colonial wall stencils and stucco finishes, we found the variety of innovations astounding.

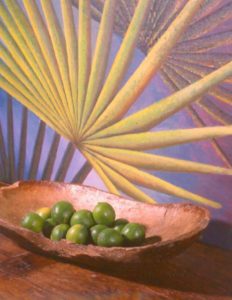

Christened by our early experiences, we soon found ourselves further immersed in documenting the nuances of Mexican design. Serendipity brought us to cattle ranches, sugar estates and bustling open-air markets, where we were drawn to well-worn display surfaces revealing rich patinas and wood grains. Sometimes, underneath mounds of papayas and rows of candied limes, we discovered stunning turned leg tables or charming old prep tables whose myriad chop marks evidenced decades of use.

Unlike the more formal environments of the cities, furniture had a multipurpose life in the countryside; it was shared by many and used for a variety of functions in myriad locations. Whether needed for marketplace displays, home or workshop use, or religious celebrations and community fiestas, one piece might be used for every setting and moved back and forth according to its owner’s activities.

MEXICAN TABLES

The Mexican table is cherished for what it represents—a warm hearth, sustaining food, a sense of nurturing and nourishment that goes far beyond the kitchen. The focal point of every home, mesas (tables) provide the quintessential gathering place for family meals. Some are grand, some are modest, but they all hold an important place in nearly all activities.

Since Colonial times, display tables, mesas de carniceros (butcher tables), and even altar tables have kept company together at the local market. Certainly one of the easiest places to see the tremendous range of shapes and sizes, the mercado contains a smorgasbord of design styles. The most prolific are the simple dining tables and benches found at market-stall restaurants. These handcrafted pieces feature mortise-and-tenon construction and often beautiful legs—turned, painted, square or carved—each kind with its own subtle design characteristics.

Visits to the marketplace have revealed tapered-leg tables from Durango displaying onions and radishes, shorter painted tables holding old scales for weighing almonds, and bakeries in which once-sharp corners and molding detail have been softened over time by decades of people brushing against their sides.

Regional styles are distinct—tables from the colonial town of Queretaro feature conservatively turned legs, whereas those of coastal farming towns in Guerrero have simple squared legs with stretchers. Even in more decorative forms, the beautiful chip-carved pine of Michoacán is distinguished from the turned legs and apron cutouts of northern Chihuahua. The predominant ranch-style table features square-legs, A-frame construction and end stretchers higher than those at the side. The mortised stretchers sometimes joint the legs to create a box-like enclosure. This particular style can be altered to become a functional desk with ample leg room by removing the front stretcher.

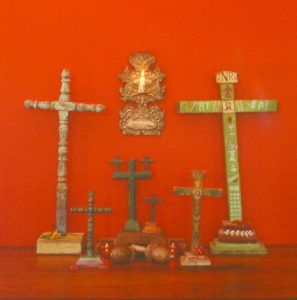

Inside most every Mexican home, the altar display, usually staged on a table or a shelf, serves as a sort of mecca for family keepsakes and religious items. Lovingly assembled atop a mesa de altar (altar table), are candles, containers of fresh or paper flowers, carved-wooden santos, various handmade crosses and family photos of loved ones.

Found in butcher shops and at the marketplace, mesas de carniceros are constructed of hearty proportions to withstand the chopping of butchers’ cleavers. Two vertical beams rising from the side of the table support a horizontal beam with iron hooks from which fresh meats can be hung. These tables make ideal prep tables, the iron hooks useful for hanging anything from heads of garlic to pots and pans. No use is ruled out—vanilla candles were seen draped from such hooks in an open-air market adjacent to the local church.

WOODS

The woods used in Mexican country furniture were predominately mesquite, sabino (Mexican cypress), pine, heart pine, Spanish cedar, parota, and occasionally, walnut, mahogany and cottonwood. Mesquite, one of the most durable hardwoods, was widely used as it was found from the Sonoran desert all the way down the west coast of Durango, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, Nayarit, and then inland to the Hidalgo/Guanajuato area. Both mesquite and sabino were sought for their tremendous strength and natural ability to repel insects.

FURNITURE AREAS

In the northern state of Chihuahua, furniture is usually made from pine, is fairly minimal in design, and is almost always painted, as it helps preserve the wood. Panels can be flat or raised, and the favored decoration is a scalloped or cutout copete (crest) attached to the top of armarios (armoires) or roperos (wardrobes) and trasteros (cupboards).

South of Chihuahua in Zacatecas, benches are decorated with undulating scallop designs resembling waves. Panels in cabinets tend to be raised and come in a variety of designs. Tables usually have signature-design cutout braces under the skirt and in each corner.

In the nearby states of Jalisco, Aguascalientes and Guanajuato, the styles are much heavier and are crafted from mesquite and sabino. These styles are also more influenced by the Colonial furniture traditions of the 17th and 18th centuries. In the southern state of Oaxaca, chip-carving decorates the benches and cabinets, while tables are generally made from cypress, Spanish cedar and pine. Long, slender tables with A-frame legs and stretchers are common, as are single-slab tops. Chip-carving styles are also very prolific in Michoacán’s Lake Pátzcuaro region where the majority of pieces are pine, as this area has large reserves of pine forests.

Throughout the rural landscape, carpinteros in provincial towns and villages crafted elements from their own traditions and resources. On occasion they even interpreted Spanish influenced styles that had made their way naturally from the cities to the countryside—through families moving to the country or storing old, broken pieces in rural barns, say. Such interpretations were, of course, simplified or streamlined to be practical and durable in rural settings. Carved lyre legs became sturdy A-frame legs; ornately carved panels on armoires were streamlined into handsome flat-panel styles; lathe-turned spindles on cupboards were sometimes simplified into slats.

CARVED ELEMENTS

The variety in style, design and shape of Mexico’s utilitarian vessels and carved wooden objects is astounding: old grain-measure boxes, tortilla presses, sugar molds with conical indentations, bateas (dough bowls), molcajetes (stone mortars for grinding spices), ceramic pots, gourd bowls, spoon racks and chocolate whisks. Many of these culinary treasures have surfaced in today’s modern homes, as sugar molds now display candles on dining tables, bateas show off beach glass collections and morteros, once used for crushing wheat or coffee, now hold magazines. Cheese presses, without their original vices and screw nuts, make handsome side tables with the addition of iron bases.

No two of the vessels and objects are alike, and each piece holds history in its carving. Wooden stools carved from tree trunks are often found in the shapes of animals, sometimes half sculpture/half furniture. Echoing simpler times, the objects may look commonplace in their original contexts, but once placed in contemporary settings, they become multifaceted, standing on their own as thought-provoking sculptures and furniture whose decorative details proved a pleasing reminder of Mexico’s rich history and skillful craftsmen.

Even unassuming objects, many no longer in use, beautifully ornament their surroundings with wit and charm when placed in new contexts. Old hacienda machinery molds when grouped together in multiples, acquire a whole new decorative dimension. A row of old lock plates on a mantel, or a threesome of old painted spindles–salvaged from broken window guards—displayed on a colorful wall emphasize the subtle structural distinctions existing in a single form.

The delight is often how these objects hold our attention in new contexts, adding a refreshing flavor to our personal spaces. In a modern Florida home, old wheat mortars play subtly with a pair of sculptural stepladders beneath an abstract painting. In Banana Republic stores, Mexican coffee and grain mortars have been used to display classic sweaters and clothing.

On a remote ranch in Jalisco we photographed mesquite workbenches–designed with hearty proportions to withstand heavy wear—along with beautifully carved ox yokes and bebederos (troughs) which held livestock feed. Over the years, many of these objects have been adapted to new functions as bebederos now flower as planters and ox yokes are easily fashioned into table bases. Old filter stones, once used for filtering water, have also been given extended lives as decorative flower vases, with the addition of new iron stands. Even old worn wheel hubs have evolved into simple lamp bases.

TRUNKS

One of the most common pieces of furniture found throughout all the states of Mexico, the baúl, or storage trunk is a treasured piece in the home. Crafted from Spanish cedar, sabino and mesquite, many baúles feature rounded or domed tops, detailed chapas (lockplates) and matching bases with simple turned legs. Inside, they often bear the personal signature of their owner(s). Interior lids are usually lined with decorative paper or prayer cards, and often feature small photographs of family members and paintings of patron saints.

In colonial times, large arcónes, or wide chests, were used in churches and convents to store vestments and chalices as well as sacred documents. Many arcónes featured feet at the corners, ornate lock plates and iron strips used for joint reinforcement.

ARMOIRES

Armarios (armoires) are used in both in homes and businesses to store valuables, records and sometimes clothing. These enormous cabinets are crafted with built-in drawers and carved, or raised-panel, full-length doors. Many early armarios were painted with decorative floral designs, religious icons, or city scenes, and were usually the most important and valuable pieces of furniture in the home. As they were expensive, armarios were often out of reach of many Mexican families and only found in the wealthiest households.

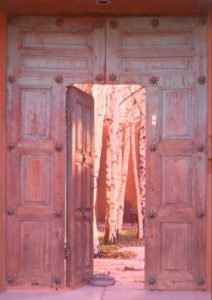

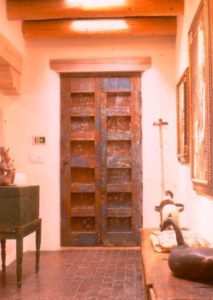

DOORS

There is no end to the style and variety of doors seen in Mexico. The only constant is that most doors come in pairs, the planks held together by iron braces and large round-headed clavos (hand forged nails). The larger the door, the heavier and thicker the wood used. The massive doors of haciendas, churches, and government buildings required oversized clavos, often three to four inches in diameter, their decorative heads filled with brass. These larger chapetones were often shaped into stars or ornate designs. The grandest in scale, záguan entrance doors still exist in the old colonial towns. They radiate a compelling sense of history, for they were built large enough to admit wagons into a home’s inner courtyard and usually had smaller doors set within the larger ones, allowing pedestrians to enter without opening the larger pair.

As the homes in most villages and towns were built close together for security, the colors, textures, and details of their doors can be viewed directly from the sidewalk. From walking a single block, one can experience centuries of wear, old braces, native repairs, and heavily adzed surfaces. The various designs range from raw unadorned wood to raised rectangular panels, raised diamond patterns, grooved-panel outlines and fluted doors. On some, important occasions, dichos (pertinent sayings), or names of respected or noteworthy family members are carved into lintels above the front door.

Today, weathered Mexican doors are being restored and adapted to a variety of architectural settings. They make the transition to doors on entertainment units, closets, and master bedrooms, and are designed into headboards and tables as their simplicity and time-honored presence compliment many interior design styles. Single shutters and doors make the transition to headboards with the addition of clean-lined contemporary iron bases and iron finials. The simplicity of the iron complements the warmth of the old wood, a comfortable coexistence in contemporary interiors.

COLOR & TEXTURE

For centuries, Mexico’s compelling colors have provided a vibrant and powerful presence to its architecture and traditional arts, beginning with the pre-Hispanic civilization’s boldly painted pyramids, colorful murals and stucco ornaments, through the Spanish Colonial haciendas awash in deep reds, ochres or blues, to today’s modern houses splashed in watermelon pink and pistachio green, the color legacy in Mexico is long and rich.

An essential form of self-expression, color has long been used to represent spiritual beliefs and cultural traditions. In fact, color and its attendant symbolism remain pivotal to the Mayas’ view of their cosmos. A color diamond signifying the physical world was at the core of their view of the universe. White, yellow, red and black each had a place corresponding the four cardinal directions of north, south, east and west, along the path of the sun.

In Mexican architecture, interior walls bathed in vibrant hues are given texture with the addition of colonial style stencil patterns or wainscots in contrasting colors. Many exterior stone walls, stuccoed and painted with traditional lime-based recipes, feature ornate stucco and stone details around doors and windows and stone-chinked surface patterns. Called rajueleado, this masterful stone-chinking tradition reinforces stuccoed surfaces and adds textural dimension and depth to walls.

Today’s architects and preservationists working in Mexico continue to herald the benefits of natural color pigments, lime-based paints and stucco finishes. As lime-based paints and stuccoes are compatible with stone walls, cal (lime)-based recipes encourage walls to “breathe,” allowing moisture to escape without damaging painted surfaces. Natural paint pigments are also highly favored, as they are more resistant to ultraviolet light, making them more lightfast than synthetic paints.

As our world grows increasingly complex and technology distances us from our own traditional ways, it makes sense that we are drawn to the qualities manifest in traditional Mexican architecture and antiques. There’s no denying the appeal of handcrafted wood and chiseled stone. We believe in the beauty and artistic power of the designs, in their lasting value, and in the skill of their creators. The character they bear from the effects of time, weather, and touch reassures us, perhaps tapping into a distant longing for simpler times when craftsmen took pride both in the quality and the sturdiness of their work.