I am not now, nor have I ever been a member of the Communist Party (although I did subscribe to the Daily World during the wild and woolly Sixties), but a visit to Leon Trotsky´s house in Coyoacán has affected me beyond all my expectations.

It reminded me of my youth when I imagined, however foolishly, that humanity might be “redeemed” by politics. A belief that seems uniquely absurd from this cynical vantage point in the early aughties.

What got to me most was Trotsky´s kitchen. On one side of the room sits a gas stove exactly like the one David and I had when we moved to San Miguel. The damned thing blew up one time when I tried to light it. A century´s worth of soot, and an old pillow someone had stuffed up the chimney, and an abandoned bird´s nest came crashing down from the exhaust hole in the ceiling high above. It filled the kitchen with the smell of my singed beard and arm hair and covered my daily Eddie Bauer sackcloth with ashes. I hope more fragrant delights emanated from this gas stove in Coyoacán in the late 1930s.

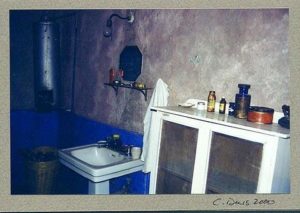

On the other side of Trotsky´s narrow kitchen is a porcelain wash basin and lead splashboard over which a few ramshackle shelves display the same talavera crockery from Dolores Hidalgo we´d bought years ago to stock our own cocina. You know, the deep brown kind with painted birds and fluted sides you use to cook frijoles de olla, and the especially brittle, gaudily-flowered kind that cracks if you drop a hot tamale or a bottle of Sol on it. There is even a white pottery tray or two like ours from Tzintzuntzán and wooden spoons and spatulas, just like the ones I used to stir my refritos this morning.

I imagined Leon peeking in from the dining room saying, “What´s for dinner, Natalia? Yum, smells like borscht again.”

Some of the Casa de Trotsky´s on-line literature alludes to the possibility that Leon is still with us in Coyoacán; that his ghost sits in the delicious sunshine in the garden by the white day lilies. Or walks under the feathery jacaranda. Or feeds his rabbits in the wooden hutches at the far edge of the yard. Trotsky would probably be horrified at the prospect. Afterlife, indeed!

Eight straw-bottomed chairs painted brown and yellow surround the long Trotsky dining table, which is covered with a yellow-checked plastic table cloth trimmed with blue and pink flowers. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, famous Coyoacán denizens and the Trotskys´ sponsors, probably ate at that table before Diego fell out with Leon (over his rumored dalliance with Frida, perhaps?).

The blue-washed walls make the room cool and inviting. I could hear the toasts and see the cheerful ghosts sipping vodka out of green tequila glasses.

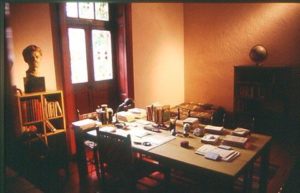

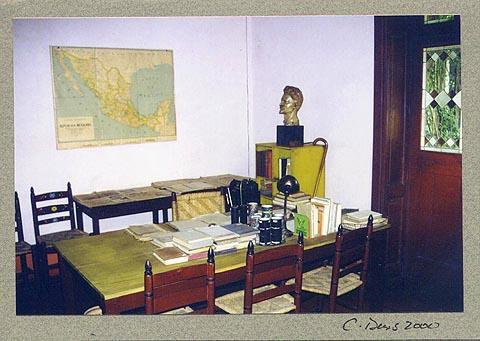

Leon´s desk, littered with papers and bottles of ink to dip his pen in, a rocking blotter, a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles, and a tract entitled Adolph Hitler and Wilhelm III, marks the exact spot the final attack on his life occurred. A young Catalan Stalinist and playboy poseur, having gained the exiled family´s confidence, entered Leon´s study and cracked him in the skull with an ice ax. Trotsky died the following day, August 21, 1940, at sundown. Trotsky was sixty. His last words were about the Fourth Internationale he had been planning that he hoped would bring down the Stalinist terror.

Trotsky knew Stalin was just another Hitler in disguise.

Trotsky´s wide-brimmed straw hat and his painted walking stick lie on his and Natalia´s bed. Blue-and-white-striped bathrobes, a brown suit, and several somber dresses still hang behind a partially-drawn, rough brown curtain in a makeshift closet in the blue bathroom. A towel hangs above the porcelain bathtub and Trotsky´s razor and shaving brush are on a small glass shelf above the wash basin.

Natalia´s face powder and a perfume bottle or two and some druggist´s remedies neatly line a wooden shelf. I couldn´t help imagining Trotsky sitting democratically on the small throne in the corner of the bathroom next to his grandson Stefan´s (or Esteban´s) bedroom.

In the hallway leading to the sleeping quarters you can see the deep bullet holes blasted in one wall on May 24, 1940, by a bunch of thugs led by Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siquieros, another staunch Stalinist, following old Joe´s orders to get the troublemaker Trotsky at any cost. Trotsky escaped unharmed, almost miraculously, but the gunmen abducted and later killed his young American office helper and security man, Robert Sheldon Harte.

After Harte´s body was found alongside the road to Desierto de los Leones, Trotsky commissioned a plaque and had it placed on the side of the garage at the front of the house. It says, simply, “In Memory of Robert Sheldon Harte, 1915-1940, Murdered by Stalin.”

Trotsky surely suspected that this foreshadowed his own death. Stalin had sentenced him in absentia to die in 1937 for supposedly being a traitor to the Soviet Union, and Trotsky knew Stalin had spies and murderers willing to do his bidding all over the world.

What really aggravated Stalin about Trotsky was his advocacy of “perpetual revolution,” an absolute essential to the democracy Trotsky envisioned was necessary for communism to work. I think what he meant was that things must not become ossified and bureaucratized. Trotsky also thought that communism could not take hold in one country alone. It must be worldwide, or not at all.

Stalin had other plans – namely his own perpetuation (he lasted some 26 awful years) at the helm of a powerful, non-withering-away Soviet state and the out-and-out murder of some 30 million people who, in one way or another, Stalin felt were against him.

I don´t really know about any of this, as I am no communist, but hindsight makes me wish that Trotsky had had a chance to prove himself. I can only imagine how differently the world might look today had he outlasted Stalin.

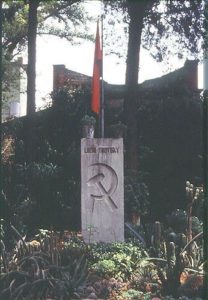

The ashes of Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia are interred in the yard of the Casa de Trotsky. They lie under a tombstone (designed by Mexican painter Juan O´Gorman) and a simple red flag.

Trotsky´s grandson, Esteban Volkov Bronstein, whose bedroom was next to Leon and Natalia´s, is now a 72-year-old Mexican citizen and engineer living in Mexico City. He occasionally shows off the family´s former home in Coyoacán to visitors. A class in icon making and restoration is held on Sundays in one of the workshops on the grounds.

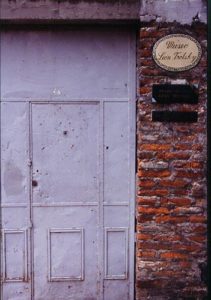

The museum is run by the Instituto del Derecho de Asilo y las Libertades Públicas, or Institute for the Right of Exile and Public Liberties, in memory of Trotsky´s own exile. Museum hours are 10:00 to 17:00 hours, Tuesday through Sunday. Admission is $10 pesos. It is located at Avenida Rio Churubusco 410 in Colonia del Carmen in Coyoacán. You can take the light-green Metro line (number 3) to Coyoacán station and on Avenida Universidad going south catch a combi labeled “Todo Churubusco y Aeropuerto.” The combi will let you off directly in front of the museum.

Phones are 5554-0687 and 5658-8732.