Zapata’s Death

After leaving Museo Casa de Zapata your next stop in the Zapata Route is in Chinameca where he was shot. It’s quiet at the ex-hacienda Chinameca and it’s easy to feel the sadness of knowing that Zapata died there. There are three things of interest in the small town of Chinameca.

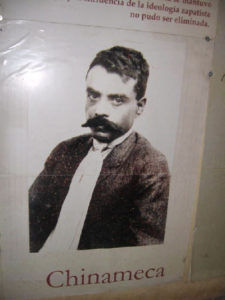

The first is a dusty display of photos and newspaper articles. It really made an impression on me to stand there and read newspaper articles about the death of the hero. Often historical figures seem so lost in the past that we have trouble even picturing them, but not in this case. Here was a newspaper article just like I read today, describing the events as if they had happened the day before – which was the case at the time that the article was type-set.

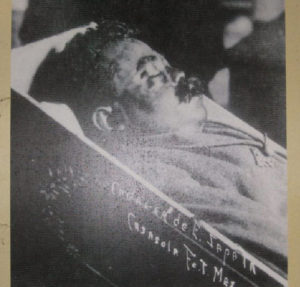

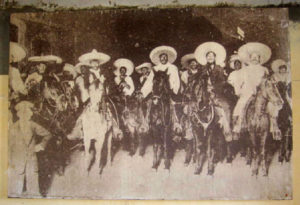

The displays here seemed to be old ones brought from another museum, set up on the gravel floor, and covered in plastic to protect them from the dust. Although photos are discouraged, I did quickly shoot a few, which you can see here. The sadness in Zapata’s face in photos of him when he’s older has always caught my attention. He doesn’t look angry and I wonder what kept him going in the face of such sadness. There is one photo where his dead body is in the arms of other men and their faces are full of shock and grief. It supports the solemn mood of Chinameca.

The apparently second-hand museum was guarded that day by an old man, sitting on top of the desk just inside the entryway. He told us a dramatized version of how it was that Zapata was shot, complete with Zapata galloping for the exit, hanging down on the side of his horse to protect himself as his horse’s hooves struck echoing blows in the hard-packed earth.

Even more impressive than this descriptive version of the story was to stand in the place where he was shot.

The old entrance to the hacienda has been preserved, but is outside the walls of the ex-hacienda/community center. To find this, we wandered around, trying to follow the old man’s unclear directions. There was the sound of squeaking swings coming from a sun baked area teeming with kids and a periodic announcement over a megaphone from the local bakery that the buns were coming out of the oven at that moment, hot and delicious.

Finally, we learned from a quiet seven-year-old, who guided us there that you go back out to the main street and walk along the street, keeping the walls of the ex-hacienda to your left. Soon you see an old arch-style gate with a small statue of Zapata on his horse. The horse is leaping, as if Zapata had escaped the bullets and his horse was about to charge away, safe and sound.

The back side of the gate is riddled with orange-sized pock marks. These were made by the bullets that missed Zapata. There is an older man, by the name of Andrés Trujillo, doting grandfather of the boy who led us there, who has a table set up in the shade on the inside of the gate. He sells T-shirts and photos of Zapata.

I was grateful that, unlike me, my husband didn’t write the old man off as some guy who just wants money. He struck up a conversation and we had a fun time sitting in that sad place, speculating on why so many bullets missed their mark and also singing along with grandfather Don Andrés as he shared some songs that he’d written about the death of Zapata. If you purchase something from Don Andrés he’ll give you the photocopies of his songs for free. His personal theory on the wayward bullet holes is that most of the guys ordered to shoot Zapata in the back really didn’t want to hit him and aimed high instead.

If you have the time, climb the hill overlooking the ex-hacienda. Zapata’s old lookout was on this hill at a place called la piedra encimada (the rock on top of another). It’s the hill that you see as you are looking out the gate through which Zapata couldn’t exit. You follow the road that heads straight away from the gate in the direction that the statue is facing until you find your way to the summit. You can see for miles around and you’ll know why Zapata had his lookout there. You can imagine him standing there, his trusted men nearby, heart beating steadily in his chest.

Every General Must Have His Cuartel: Museo Ex-Cuartel de Zapata

The last stop in this route is in Tlaltizapán where General Zapata had his military base from 1914 to 1918.

The ex-cuartel, as it is now called is a cool, quiet, relaxing museum. For me the most imagination-catching display is that of the clothing Emiliano Zapata was wearing when he was killed. I stood for a long time trying to imagine how big he was. The pants don’t look very large, but since they were tight-fitting maybe they trick the eye. Still, it would be fitting that this Mexican hero be rather small like so many of his countrymen. True to classic Mexican museum style, no real explanation – least of all his height and weight – is posted near the clothes.

It’s all up to the imagination and I found myself conducting my own, very amateur forensic analysis. The stains – which I had to conclude were made by his very blood – on the long underwear are poignant. Just below the right waistband in the back of both the pants and the long underwear, there is a tiny, round hole. I’ve never seen a bullet hole in clothing, but it appears that he was shot in the back. Therefore, my personal forensic analysis rules out the old man in Chinameca’s version of the story.

You’ll have to come see for yourself.

As I was observing the display of Zapata’s short bed, protected by a gauzy mosquito net and wondering if Zapata really had such a lovely, lacy, hand-made pillowcase and coverlet, recorded mariachi music began to drift in, followed by the sounds of rhythmically tapping shoes. Community members were practicing folkloric dance in the shady courtyard of the museum. I thought that Zapata would probably be glad that this generation can use his ex-cuartel as a place to practice an art form so Mexican. Besides, Don Luciano told me that Zapata liked music.

When you visit this museum, make sure that you walk all of the way to the back of the grounds to see the oven built by Zapata’s men for smelting silver into coins. They needed money and, being practical Mexicans, made their own. You can still see the soot staining the bricks.

On our way to Zacatepec, after completing the Zapata Route we drove through an ash storm. Twisted sheets of carbonized sugar cane leaves were drifting down all around us, thick and hushed as a snow storm. We stopped the car so that I could try to get a picture of this phenomenon which happens periodically in areas surrounding sugar cane plantations during the time that they are burned to remove their knife-like leaves and prepare the cane for cutting. I was out, trooping around, taking everything in like Mexicans in the north experiencing their first snowstorm.

As I was trying to get a representative photo of this very un-photogenic event I was aware of the nearby sugar factory. Smoke was rushing out of its smokestacks and it was producing a sucking whir as the people inside processed the sugar. I imagined that in their day, Zapata and his men would have hated to see the ashes falling and hear the sounds of the sugar industry that was gobbling up the heart of their land. Now the land is in the hands of the people and they make money on the sugar industry, as Zapata wanted.

Stop 1: Museo Casa de Zapata in Anenecuilco

Cost: 30 pesos. Open Tuesday through Sunday.

Anenecuilco is just a few kilometers south of Cuautla on the highway that leads to Ayala. If you are driving, you will be glad that the entire Ruta de Zapata is well marked with blue signs.

To follow these signs through downtown Cuautla, keep your eyes peeled for a sign in a traffic island in the middle of a “Y.” At this “Y” you will bear right. Next, at 2 de Marzo, you will be forced to take a right due to a transformation into a one way street. Next, take a left onto Dalias Matamoros (which will turn into the highway to Ayala). You will immediately see Parque de la Revolucion with a large statue of Zapata to your right. Don’t miss this because he is buried there. You will go under a set of pointed arches that read, “Bienvenidos a la Tierra del Jefe” (Welcome to the land of the boss). Let the sugar cane growing along the highway make you think of the days when Emiliano Zapata rode the area on his horse. In less than six kilometers, you will see a sign to turn right at a small plaza with a gold colored statue.

This is Anenecuilco. (It has been 96 years since the signing of the Plan de Ayala and the town is still very small. Imagine how it must have been when Zapata lived there.) On that road, you will cross a bridge, go up a hill and turn left at a “T” (yes, there’s a sign!). The museum will be on your right and unmistakable with an open fence of metal tubes and the soaring white tent that protects Zapata’s house.

Stop 2: Chinameca, where Zapata was killed

Cost: voluntary donation

How to get there: Head south from Anenecuilco, through Ayala and Moyotepec. At Moyotepec, bear left at the “Y” and keep heading south. Immediately after San Rafael de Zaragoza, take the left toward San Juan Chinameca. This left is well marked with a Ruta de Zapata sign. Before you get to Chinameca you will go through a four-way stop. Don’t turn. After the four-way stop, you will go up a hill into Chinameca. The museum is well labeled and is almost the first thing you see upon arriving in Chinameca.

Stop 3: Museum Ex-Cuartel de Zapata

Cost: 30 pesos open Tuesday through Sunday

How to get there: From Chinameca, head back down the hill the way you came. At the “Y,” bear left toward Tlaltizapan, rather than back north toward Anenecuilco. Once in town, follow the blue Ruta de Zapata signs.

How to get home:

If you are staying in Cuaulta, follow signs to Tempila Nuevo, then to Cuautla. If you are staying in Cuernavaca, follow signs to Zacatepec, then to Cuernvaca. You can choose to take the faster toll road for about 50 pesos.

Links to Additional information:

- Aerial view of Museum in Anenecuilco

- Interview (in Spanish) of Luciano Luna Domínguez

- Part 1 – The Land Was in His Heart