As you walk toward the main square from the bus terminal in Dolores Hidalgo, it’s hard to imagine the impassioned frenzy that heated this Mexican village on September 15, 1810. Here, on the balcony of his home, the town’s beloved priest, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, yelled “El Grito de Dolores,” the Cry of Independence. It was a cry that changed the history of North America, and, indeed, the world.

In the 1800s, Father Miguel Hidalgo, a brilliant and off-beat Jesuit priest, was an enlightened thinker and reader. More importantly, he was a champion of the common man. The 50-year-old, white haired theologian with lively green eyes practiced an equality not common in his day. In his living room he welcomed poor Indians, along with crillos. Also, during his seven years in Dolores, Padre Hildalgo encouraged industrialization. He taught the people silk worm raising, harness making, blacksmithing, weaving, leather tooling, wine and olive oil production, and pottery. His influence on the latter is still evident.

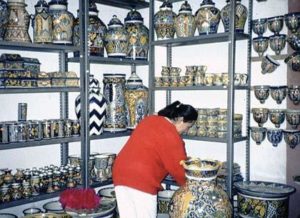

Today, in this town in the high plains of Mexico’s Bajio, small shops and vendor stalls line the cobblestone streets. Women and children, squatting on curbs, sell juicy limes and just-picked avocados. Vases, hand painted with bursts of brilliant flowers and squiggly designs, decorate the sidewalks. This is one of the best places in Mexico to buy Talavera Pottery (a porcelain type pottery introduced by Father Hidalgo). Streets here are lined with shops, where prices, relatively unaffected by tourist influences, are low. In the back of the store, you can usually find craftsmen at work painting the pottery.

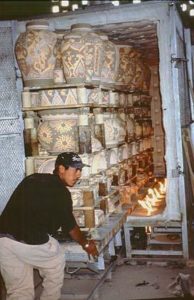

Mora Alfareria, Oaxaca No. 18, a shop only a couple of blocks from the tourist information center, is a major exporter of pottery to the United States. You can watch workers paint and fire (in kilns at 900 degrees Celsius) the vases, bowls, platters, and place settings. Another excellent street for pottery shopping is Calle Puebla, where you’ll find several shops between buildings #50 and #58.

The laid back atmosphere of present-day Dolores Hidalgo is a far cry from the morning of “The Cry” that signaled the start of the country’s independence from Spain. On that Sunday in 1810, the town (then known as just Dolores), was swarming with church-going Indians and peasant farmers. Father Hildalgo roused them and crillos (people of Spanish descent born in Mexico) to rise against the gachupines (the ruling class, born in Spain). He urged the crowd to follow him into battle. It wasn’t a prepared, written speech, so no one is certain exactly what Hidalgo said, but he probably included phrases such as “long live freedom.” The scene is reenacted yearly on September 15 throughout Mexico.

After “The Cry,” Miguel Hidalgo (he wasn’t an active priest at the time he led the revolution) and his countrymen marched 20 miles to San Miguel el Grande (now San Miguel de Allende), to join the forces of criollo military general, Ignacio Allende. About 1,000 troops strong, they marched toward Guanajuato (which is now the state capital). Within a week, their ranks swelled to 25,000 and ultimately to 80,000. Yet, it took another 11 years, and much bloodshed on both sides, before Mexico achieved independence from Spain.

Miguel Hidalgo, along with three other revolutionary leaders, were executed in 1811, and for 10 years, their heads hung in public view, encased in steel cages in Guanajuato. This display, intended to scare and suppress the populace, may have had the opposite effect, because today, almost two centuries later, Hidalgo is still a national hero.

The best part about Dolores Hidalgo today is that the town, population 60,000, is relatively free of tourists — in spite of it being “The Cradle of Independence.” The non-tourist atmosphere may change soon, however, as more Norteamericanos and urban Mexicans flock to this historic place.

The village is small and compact, so it’s easy to find your way around. When we first entered the Visitor’s House (tourist information center), two young women who spoke only Spanish were on duty. Later in the day, there was an English-speaking person on duty.

Ornate churches and historic monuments dot the town like candy sprinkles on a cupcake. You can visit Casa de Don Miguel Hidalgo, where the beloved priest lived from 1804 to 1810. The home is filled with exhibits of furniture and documents from that historic period.

The Independence Museum, originally a prison (Hidaldgo freed the inmates, who joined his forces) is a historical art center. “We love Father Hidalgo,” a young woman told us as she guided us through the Museo de la Independencia. We enjoyed lunch in the modest cafeteria in the fountained courtyard. Piano music floated in from an adjoining room.

Handcrafts and agriculture are the primary occupations in the town and surrounding countryside. Cottage industries include pottery, metal crafts, saddlery, tinware, and lapidary. You can visit the workshops (inquire at the Visitor’s House) and watch the artisans at work.

In the shops, clerks are patient. We entered a hat store which displayed at least 300 different sizes and styles — from rodeo cowboy to southern belle. The first hat was too large. I said “mas grande,” thinking I was saying it’s too big. Instead, the eager, young clerk brought me a wider-brimmed one. “Mas grande,” again brought an even larger hat. There seemed to be no end to how big the hats could get as I repeated, “mas grande.” We both laughed, when I realized I should have said, “demasiado grande.” Or maybe I should have merely said, “too big.”

The townspeople here aren’t as accustomed to tourists as in more well-known Mexican destinations. Standing on street corners taking photos, we were the attraction of the day, the center of attention. Mothers asked us to take pictures of their children. Others scurried away from our cameras. From most, we got shy but friendly glances.

After shopping, we rested on the wrought-iron benches in the tree-shaded main plaza, watching to-die-for scenes of old men, young women, babies, and mariachis. A bigger-than-life bronze statue of Miguel Hidalgo takes center stage in the park. Across the street, Our Lady of the Sorrows church, with its elaborately carved facade of rose-colored stone, anchors the main square.

Ice cream vendors are a major attraction in the park. They offer dozens of exotic flavors, from shrimp and alfalfa to avocado and tequila. My friend ordered a mango cone, looked at her watch and said, “This should hit in about three hours.” It did. She had terrific stomach heaves. Another friend ordered vanilla, with no ill effects.

The main reason to visit Dolores Hidalgo as soon as possible is because in a few years it will undoubtedly change. Its unpretentiousness and low key atmosphere are central to its charm. Those attractions are hard to beat — and even harder to find.

Getting there: The nearest airports are in León and Querétaro. First class buses from Mexico City are convenient, comfortable and inexpensive. Expect to pay under $10 from Mexico City. If no direct service is available at your time of arrival, best bet is to get a bus to San Miguel de Allende (they run more frequently) and change buses for Dolores.

There are several small hotels in Dolores Hidalgo; lodging is plentiful in San Miguel de Allende, only 25 miles away (40 minutes by bus).