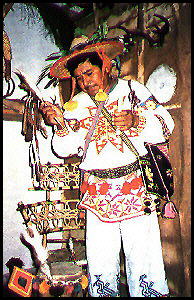

Deer and wolves that speak to man, arrows that carry prayers, serpents that bring rain or impart skill in embroidery, pumas that are messengers of the Gods — are all real in the Huichol belief system. These are the proud Indigenous people seen around Puerto Vallarta in their colorful embroidered clothing. “Huichol” (pronounced Wettchol), according to Norwegian explorer Carl Lumholtz “is a corruption of the work Vishalika or Virarika, that the Huichols call themselves, the word signifying ‘doctor or healer,’ a name they fully deserve as about one-fourth of the men are shamans.”

The Huichol Indians live in virtually inaccessible areas of the states of Nayarit and Jalisco, straddling the Sierra Madre Occidental in an inhospitable region of about 15,000 square miles in scattered kinship settlements (ranchos).

In the past thirty years, about four thousand Huichols have migrated to cities, primarily Tepic, Nayarit, Guadalajara and Mexico City. It is these “citified” Huichols who, because of the need for money have drawn attention to their rich culture through their art. To preserve the ancient beliefs and ritual ceremonies, they began making detailed and elaborate yarn paintings. The Huichols have only an oral tradition and no written language (thus the many differing spellings of Huichol words). “Through their artwork, the Huichol Indians encode and document their spiritual knowledge” notes Susana Eger Valadez in Huichol Indian Sacred Art. In their artwork the Huichol express their deepest religious feelings and beliefs acquired through a lifetime of participation in ceremonies and rites.

“From the time they are children, they learn how to communicate with the spirit world through symbols and rituals. Thus for the Huichol, yarn painting is much more than mere aesthetic expression. The topics of these yarn paintings reflect Huichol culture and its shamanic traditions. Like icons, they are documents of ancient wisdom.”

One sees their fine art work for sale at many locations in Puerto Vallarta. From the small beaded eggs and large jaguar heads to the detailed yarn paintings, each is related to a part of Huichol tradition and belief.

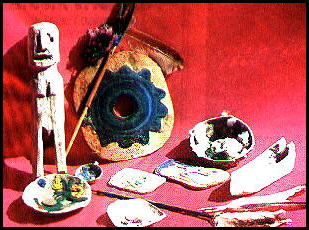

Beginning about thirty years ago, the yarn painting evolved to its high state today from the nierika. A small square or round tablet with a hole in the center is a nierika (nearika) or sacred magical offering. These tablets are covered on one or both sides with a mixture of beeswax and pine resin into which threads of yarn are pressed. Nierikas are found in all Huichol sacred places such as temples, springs and caves. The nierika, in ritual use, is a face; of the sun, of the earth, of a deer, the wind, the peyote, and the face of the man making the offering. The nierika facilitates the entry into the other “spiritual world.” For the Huichol, there are five directions, each of the cardinal points and the fifth is the spiritual, source of visions, power and enlightenment.

A nierika is called a mirror with two faces, and for that reason often both sides are covered with yarn designs and the hole in the middle is considered a mirror or often a small glass mirror is used. This ‘hole’ or ‘mirror’ is the magical eye through which man and God can see each other. The mirror makes the gods pay attention to the petition, which places a real obligation on the gods to grant whatever is portrayed on the nierika. For example, offering nierika to the mother goddess or rain goddess ensures rain, but other rituals must be observed as well, i.e. the ritual slaying of a deer.

The first large yarn paintings were exhibited in Guadalajara in 1962, a direct outgrowth of the nierika — simple and uncomplicated. At present with the availability of a larger spectrum of commercial dyed and synthetic yarn, more finely spun yarn paintings have evolved into high quality works of art. Realism, based on mythology, is the basis of yarn paintings.

Beaded bowls (jicara in Spanish, rakure in Huichol) evolved in this same manner. Beadwork originated as an art form long before the Spanish Conquest of the indigenous peoples. Instead of the glass seed beads utilized today, bone, clay, coral, jade, pyrite, shell, stone turquoise and seeds were used. These were often colored with insect or vegetable dyes.

Originally the beads defined the waxen figures pressed into gourd prayer bowls to be used as offerings (as niekira) and/or petitions to the gods and goddesses. The Huichol believe that just as one drinks water from the gourd bowl the gods drink up the petitions in the bowls and subsequently understand the prayer better. Color defines the god or goddess petitioned: for example blue signifies Rapawiyeme (“rapa” is the tree of rain); black is Tatei Aramara, the Pacific Ocean, place of the dead, great serpent of rain; red indicates Wirikuta, location of the birthplace of peyote, deer and the eagle. With the development of finer, smaller beads, more detailed work s are now seen, not only on gourds but on wooden jaguars.

Peyote cactus is much revered by the Huichol, a veritable gift from the gods. Through the use of peyote, the Huichol create the elaborate designs used in their artwork. It symbolizes the essence, the very life, sustenance, health, accomplishment, good fortune of the Huichol. Plus through peyote’s hallucinogenic effects, enlightenment and shamanic powers can be achieved. Annual pilgrimages are taken to Wirikuta to collect the peyote. Only the “purified ones” can participate in the harvest or the peyote will not be found.

Peyote mandalas or neakilas (nierika) symbolize the entrance to the spiritual world. As important power objects they are often found at the center of yarn paintings. Each mandala is individual, mirroring peyote vision trances.

Utilizing many of the same sacred designs and patterns as seen in yarn painting and weaving, the Huichol create anklets, bags, belts, bracelets, chokers, earrings and rings with the seed beads. “Life is a constant object of prayer for the Huichol, it is, in the conception, hanging somewhere above them, and must be reached out for,” explains Lumholtz, “thus all phases of their lives are prayer — the planting, harvesting, peyote pilgrimages — all art, weaving, bead work, face painting and yarn paintings, embody prayer within symbols.

With this introduction one can better understand the Huichol, their art and their constant communication with the spiritual realm. Ramon Mara Torres sums it all up by observing, “This ancient art, modernized as a result of circumstances entirely outside Huichol culture itself, has become like an exotic flower, eagerly sought after by the conocenti.”

Adapted from the The Huichol Center for Cultural Survival with the kind permission of Susana Eger de Valadez.