Note: Click images for summary biographies of the key individuals

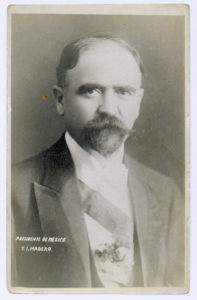

Mexico in September 1910 could be compared to a shiny apple whose glossy skin conceals a putrifying interior. But the corruption underneath was still a secret to the rest of the world. Porfirio Díaz, the old dictator who had held power since 1876, was probably the most respected political leader on earth. Tolstoy called him a “prodigy of nature,” the German Kaiser awarded him his country’s highest decoration, Andrew Carnegie praised his “wisdom and courage” and even the progressive Teddy Roosevelt characterized him as “the greatest statesman now living.”

September 16 was a banner day in Don Porfirio’s life. He had celebrated his eightieth birthday the day before and now, his beautiful young wife beside him, he was reviewing a massive parade that marked the centennial of Mexico’s independence. Mexico City’s boulevards rivaled those of Paris and — as yet unpolluted — its high altitude and clean, cool air made it a magnet for foreign visitors.

Behind the glittering façade was another Mexico — one of poverty, illiteracy, exploitation and peonage. Though himself an Indian, Díaz was completely beholden to a European-descended elite and the country’s indigenous population was horribly oppressed. Major industries were controlled by foreign interests, the illiteracy rate was 80 percent, infant mortality averaged 439 per thousand, life expectancy was 30 years, 50 percent of all houses were classified as unfit for human habitation and in Mexico City 16 percent of the population was homeless. Yes, Díaz had brought about social peace — mainly through recruiting bandits into his dreaded rural police — but he had done so at a terrible cost.

Heading the opposition to the seemingly impregnable dictator was as unlikely a rebel as could be imagined. Francisco Madero, then 37, was a member of one of Mexico’s richest families. In a country where two-fisted drinkers with hearty appetites and swaggering macho lifestyles are extravagantly admired, Madero was a vegetarian, teetotaler and spiritualist. Small in stature, he had a high-pitched voice and his belief that he would one day be president of Mexico was conveyed to him on a Ouija board during a séance.

And he wasn’t all that much of a revolutionary. Leery of far-reaching social change, Madero concentrated all his energies on Díaz’s repeated violations of the no-reelection principle. Except for a four-year interval when a puppet held the office, Díaz had been president since 1876. In July 1910, in a crudely rigged election, he had defeated Madero and was poised, at age 80, to begin his seventh term as President of Mexico.

Fortunately for Madero, he would acquire effective allies.

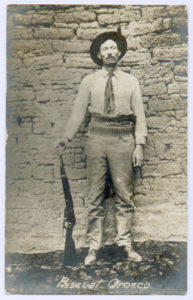

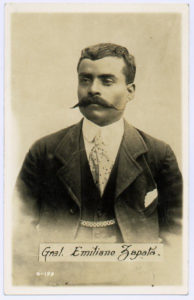

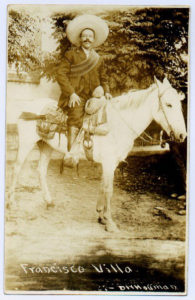

Stemming from completely disparate backgrounds, they included intellectuals like Chihuahua Governor Abraham González, a rough mule skinner named Pascual Orozco, a rancher-turned-guerrilla-chieftain from Morelos named Emiliano Zapata and a cattle rustler and bandit named Doroteo Arango who gained fame under his adopted name of Pancho Villa.

Díaz had had Madero arrested in June but released him in October. Grossly underestimating his foe, he referred to him as el loquito (“the little madman”) and ventured the opinion that he should be in a lunatic asylum rather than in prison. On release, Madero crossed into the United States and published his Plan de San Luis Potosi, which denounced the election as a fraud and called for a rising on November 20.

What happened in the next six months makes one recall Adolf Hitler’s prediction prior to his invasion of the Soviet Union: “I have only to kick the timbers and the whole rotting structure will come tumbling down.” Though Hitler’s crystal ball proved to be clouded about Russia, the prediction would have been marvelously accurate about the regime of Porfirio Díaz. Villa, Orozco and Zapata — natural soldiers with no formal military training — won a series of victories over the dictator’s dispirited troops. On May 24, 1911, Díaz resigned and sailed into exile, dying in Paris four years later.

Madero entered Mexico City in June 1911 and in October became president by a near unanimous margin in an honest election — a rare occurrence in Mexico.

For the trusting and inexperienced Madero, the honeymoon was brief. Zapata, angry with Madero’s footdragging over land reform, broke with him even before his inauguration. In March 1912 Pascual Orozco went into rebellion — but from the right. Angered at not being named governor of Chihuahua, Orozco sold out to the state’s cattle barons and became leader of a band of counterrevolutionary white guards defending the big ranchers, and their vast land holdings.

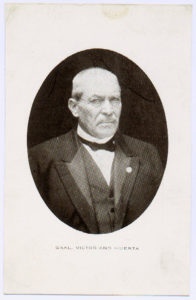

To defeat Orozco, Madero called on the services of a regular general named Victoriano Huerta. Huerta could be considered Madero’s Grant — if Grant had staged a coup and overthrown Lincoln. Like Grant, Huerta was both an able soldier and a heavy drinker. He smashed Orozco’s forces in four decisive engagements and, during the campaign, sentenced Pancho Villa to death. Though the pretext was a trivial episode about improperly requisitioning a horse, behind Huerta’s action was a deep-seated hatred of Villa. Villa — a nondrinker despite his freewheeling sexual exploits — called Huerta el borrachito (“the little drunkard”) while Huerta caustically referred to Villa as “the honorary general.” A last minute reprieve from Madero saved Villa’s life and he was instead imprisoned in Mexico City.