1877–1945) President: 1924-28

Mexico is a land of intense faith. The cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the saints on automobile dashboards, the vast crowds making pilgrimages on their knees — all attest to the depth of religious feeling in a land where the culture of the Spanish conquistadores clashed and then melded with that of terrifying Aztec and Maya deities.

But strong religious faith has a way of generating its opposite. The political power and vast wealth of the Church succeeded in engendering within Mexico an anticlericalism of unmatched ferocity. Mexico may be the land where barefoot Indian women burn candles and offer gifts to figures of the Dark Virgin — it is also the land where red-shirted militiamen burned churches, where priests hid for their lives and where a powerful, half-crazed state governor had cards printed describing him as “the personal enemy of God.”

Though this governor — Tomás Garrido Canabal of Tabasco — was an extreme example of the clerophobe in politics, it should be taken into account that he was supported and his activities legitimized by an even more powerful man: his president. That president was Plutarco Elias Calles, who held the office between 1924-28 and then ruled through puppet presidents until 1934, when he was succeeded by an independent-minded man he incorrectly believed would be the next in a succession of stooges. Calles was the leader and symbol of the anti-Catholic movement that emanated from the 1910 Revolution and proved such a powerful force in the 1920s and 1930s.

He was born in Guaymas, Sonora, in 1877. But not as Calles. His origins are obscure and his enemies would later claim that he was a Turk or a Jew. Actually, he was neither. Near as can be ascertained, he was the natural son of a woman named Maria de Jesús Campuzano and Plutarco Elias, member of a prominent local family of Lebanese descent. The boy grew up in poverty as Plutarco Elias and according to Fernando Torreblanca, who was both his secretary and son-in-law, took the name Calles from his maternal uncle, who befriended and raised him after his mother’s death. Historians suggest that this background of illegitimacy and deprivation had much to do with shaping Calles’s morose nature and fanatic hostility toward his enemies.

Before the 1910 Revolution he worked at a number of occupations — small businessman, schoolteacher, bartender (though he later became an ardent prohibitionist), and flour mill manager. But his real talent was for politics. With an instinct for picking a winner, he supported Madero against Diaz, Carranza against Huerta and Obregón against Carranza. After Madero’s victory he became police commissioner in the border town of Agua Prieta. As a military man, he helped Madero and Huerta in their campaign against Pascual Orozco and then joined the obregonista General Benjamin Hill in the struggle to oust Huerta. Though not particularly gifted as a commander, his political skills propelled him to the rank of general.

Under Carranza, he served as governor and military commander of Sonora in 1915-16. Then he took a cabinet post, as Carranza’s secretary of industry, commerce and labor. In February 1920 Calles resigned and returned to Sonora to aid Obregón in his presidential campaign. Carranza, fearful of the able and ambitious Obregón, had chosen a man named Ignacio Bonillas to succeed him. Bonillas, formerly Mexican ambassador to Washington, had spent so much of his life outside Mexico that political enemies claimed he had difficulty speaking Spanish. They called him “Meester” Bonillas and on one occasion derailed his campaign train, causing him to miss an engagement. Then they spread rumors that Bonillas had cancelled – the engagement to take a Spanish lesson.

Carranza retaliated by terrorizing Obregón campaign workers and Obregón went into rebellion. Calles supported him by issuing the Plan de Agua Prieta, a manifesto disavowing Carranza as president. The Obregón-Calles forces triumphed and Carranza was treacherously murdered while attempting to flee to Veracruz.

To fill out Carranza’s unexpired term, Sonora Governor Adolfo de la Huerta became interim president in May 1920. On November 30 of the same year Obregón was formally inaugurated to serve a regular term. Calles was by now Obregón’s right-hand man. He had been secretary of war and marine during de la Huerta’s interregnum and Obregón named him to head the all-powerful interior ministry (gobernación), from which post he launched his campaign for the presidency.

Calles showed his loyalty to Obregón during a brief but bloody rebellion mounted in December 1923 by de la Huerta, the former interim president. Though 60 percent of the federal army supported de la Huerta, Obregón and Calles won out because they had a broad base of labor-farmer support. In addition, Obregón was able to procure arms and aircraft from the United States. De la Huerta fled to Key West in March 1924 and Fortunato Maycotte, the last of the rebel generals, was captured and shot on May 14.

Though Obregón had a sense of humor, he could be ruthless when the occasion demanded. Determined not to make Madero’s mistake when he retained Huerta (who turned on him), he shot every officer over the rank of major who supported the de la Huerta rebellion. This meant that the remainder of the army, organized labor and the agrarian groups would be united in support of his heir apparent, Plutarco Elias Calles.

Calles was inaugurated on November 30, 1924, and lost no time plunging Mexico into the most severe religious crisis of her history. The 1917 Constitution contained articles which practicing Catholics considered intolerable — among them were provisions outlawing monastic orders, prohibiting religious organizations to own property and reducing clergy to the status of second-class citizens by taking away their right to vote. Obregón disliked Catholicism but was a practical man who followed a policy of applying the articles selectively — with rigor in areas where the Church was weak, leniently or not at all in regions where the Church was strong.

Calles, by contrast, was a fanatic determined to extirpate every trace of Catholicism from Mexico. On June 14, 1926, he signed a decree known officially as “The Law Reforming the Penal Code” and unofficially as the “Calles Law.” Designed to put teeth into the constitutional articles, it spelled out in specific terms the penalties for violations — 500 pesos for wearing clerical garb, five years imprisonment for criticizing the laws or inducing a minor to join a monastic order, etc.

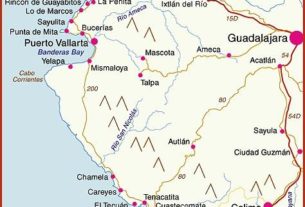

The trouble came when Calles mulishly attempted to enforce the laws in strongly Catholic west-central Mexico, particularly the states of Jalisco, Colima, Zacatecas, Guanajuato and Michoacán and even more particularly the Los Altos ranch country of northeast Jalisco, focal point of what would turn out to be the terrible 1926-29 Cristero War. Shouting their battle cry of Viva Cristo Rey! (“Long live Christ the King!”), a motley assortment of ranchers, Catholic students and workers from Guadalajara and Indians from Jalisco’s northern sierra held off the cream of the federal army for three years.

In the end, the issue was never decided by force of arms. Calles completed his term in 1928 and his successor, Emilio Portes Gil, was flexible enough to cooperate with the able American ambassador, Dwight Morrow, in arriving at a settlement which in fact granted little to the Catholics. The Portes Gil-Morrow efforts were aided by an appeasement-minded majority in the Catholic hierarchy that betrayed the Cristeros in the field.

Though no longer president, Calles continued to run Mexico. When a military rebellion broke out in March 1929, he took over as minister of war and marine and energetically stamped it out. Two presidents that succeeded Portes Gil, Pascual Ortiz Rubio and Abelardo Rodríguez, were pretty much in his pocket, though Rodríguez showed flashes of independence from time to time.

In 1934 Calles made the mistake of backing the candidacy of Lázaro Cárdenas, who proved to be both the most honest and the most radical president in Mexican history. Now rich and increasingly corrupt, Calles was moving steadily to the right as Cárdenas implemented his radical reforms. Calles soured on land reform, called the Revolution a “political failure” and, after a trip to Europe, seemed to be moving in the direction of fascism. Guessing — probably correctly — that Calles wanted to remove him, Cárdenas struck first. On April 9, 1936, he had Calles arrested and dumped over the border. When a picked detachment of soldiers and police burst into Calles’s bedroom, they found him reading a Spanish edition of Mein Kampf.

Calles was allowed to return to Mexico by Manuel Avila Camacho, Cárdenas’s moderate successor. As if to symbolize the decline of rabid anticlericalism that had gripped Mexico in the heyday of Calles and Garrido, the “personal enemy of God,” Avila Camacho publicly announced that he was a religious believer. Calles took up residence in Mexico City and there lived quietly until his death in 1945, at the age of 68.