In the preface to his monumental biography Sor Juana, the late Octavio Paz wrote, “In her lifetime [1651 to 1695], Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was read and admired not only in Mexico but in Spain and all the countries where Spanish and Portuguese were spoken. Then for nearly two hundred years her works were forgotten. After the turn of this century taste changed again and she began to be seen for what she really is: a universal poet. When I started writing, around 1930, her poetry was no longer a mere historical relic but had once again become a “living text.”

Juana Ramírez de Asbaje entered the convent of St. Jerome (San Jerónimo) in 1669 as a cloistered nun. Once she took her vows, she became Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. As Paz points out, the cloistered life in those days was not as severe as we might imagine it: “[T]he convents were small cities and the cells were apartments or even at times, small houses constructed around enormous patios.” Sor Juana’s quarters consisted of an upper and lower floor, in which each cell had a bathroom, a kitchen, and a sitting room. The nuns often brought along maids and slaves, and at St. Jerome there were three helpers to every nun.

Officially known as the Convent of Santa Paula of the Order of San Jerónimo, it was founded in 1585 by Isabel de Barrios, daughter of conquistador Andrés de Barrios, husband of the sister of Cortés. It was built in an austere style known as herreriano, named for Juan de Herrera, architect of El Escorial in Spain. After its life as a convent was ended, the building went through several transformations, once even housing a famous cabaret, the Smyrna Dancing Club.

Under the guidance of Licenciada Carmen Beatríz López-Portillo, daughter of President López-Portillo, the site was opened as a Center for the Investigation of the Life of Sor Juana, and soon evolved into its present-day incarnation as the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana [La Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana]. The building is part of the patrimony of Mexico; the school is owned by Licenciada López-Portillo.

None of our guidebooks made any mention of the convent or the university, so we set out to find it, not sure what to expect, but hoping to find remnants of the original convent. The entrance is on José María Izazaga, halfway between metro stations Isabel la Católica and Pino Suárez in the Centro Histórico, and the entrance is very inauspicious, looking much like the opening to a parking lot. [From the other three sides, the convent looks like an abandoned boarded-up fortress, and in a graffiti-lined courtyard. On the backside is a huge statue of the sitting Sor Juana that looks much like the space aliens of Roswell, New Mexico.

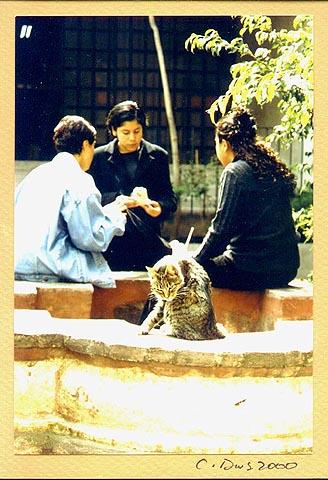

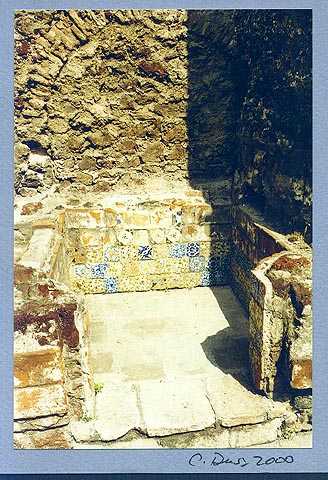

But once inside, we found a cozy labyrinth of patios, courtyards, classrooms and meeting rooms, a theater, a chapel, and offices. The largest courtyard is enclosed by classrooms, offices, and ruins of the old convent. One door opens into a modern classroom, the next into 16th-Century ruins. In these rooms the stone floors have sunk about two meters, giving them a half-basement look. Remnants of tile ovens and tile baths can still be seen.

We visited with Licenciada Soledad López Perèz, the school’s information officer, who told us about the university. The classes are tutorial (one on one) or seminar (group discussion) rather than traditional lectures. The philosophy of the institution is humanistic, and students are encouraged to investigate and think for themselves, according to the licenciada. Enrollment is about 700 students, mostly upper middle class. Humanistic degrees are offered in nine subjects: art, cultural sciences, philosophy, humanities, literature and science of language, psychology, editorial design, audio-visual communications, and gastronomy.

If you get an intellectual itch while visiting the school, there is an excellent collegiate bookstore. And if you mention Paz’s book about Sor Juana, as we did, you will discover quickly that Sor Juana, who she was and what she was like, is still a subject of lively debate. More than three hundred years ago, Sor Juana herself wrote:

I am not who you think I am

But you have given me

Another being with your pens

Another breath through your lips,

And unlike my own self

I wander among your pens,

Not as I really am

But as you want me to be.

No soy yo la que pensáis,

sino es que allá me habéis dado

otro sér en vuestras plumas

y otro aliento en vuestros labios,

y diversa de mí misma

entre vuestras plumas ando,

no como soy, sino como

quisisteis imaginario.

Or if you are just hungry, there is even a bargain restaurant on the premises that serves meals prepared by the gastronomy students.

We asked Licenciada López about restorations at the site, and she said the parts of the building that were restored had been restored to their 18th Century version, not their 16th Century one. Although the university has all the modern accoutrements-electricity and running water, telephones, computers, TV monitors, fire extinguishers, and a student population as modern, modish, and intellectual as you might see at, say, the University of Chicago, there was still the feeling that the 20th Century was just camping there.

We asked Licenciada López about restorations at the site, and she said the parts of the building that were restored had been restored to their 18th Century version, not their 16th Century one. Although the university has all the modern accoutrements-electricity and running water, telephones, computers, TV monitors, fire extinguishers, and a student population as modern, modish, and intellectual as you might see at, say, the University of Chicago, there was still the feeling that the 20th Century was just camping there.

Yet, when we walked through the ruins in one of the patios, we couldn’t get rid of the feeling that we were walking where Sor Juana had walked. We saw in the chapel an amazing thing however-a mirrored multi-tiered pyramid, its tiers lined with rows of skulls nestled in nests of pink and orange flowers. Above it were garlands of the same flowers festooning the inside of the dome over the altar. All these decorations were part of an elaborate ofrenda, or altar, inviting the spirit of Sor Juana to visit on the Day of the Dead.

There was a conference going on while we were there called Six Days of Culture with workshops on such topics as “The Feminine from a Psychological Perspective,” “The Feminine in Education,” “The Brain-Masculine? Feminine?” and “Woman: Virgin Mother or Prostitute? A Masculine Vision of the Feminine.” If the spirit of Sor Juana had come back for a visit, we wondered if she might be lingering for the conference.

Books by and about Sor Juana

- Sor Juana Or, the Traps of Faith,

- By Octavio Paz, Margaret Sayers Peden (Translator) Reprint 1990

- Paperback

Poems, Protest, and a Dream : Selected Writings- By Sor Juana Ines De LA Cruz, Margaret Sayers Peden (Translator) 1997

- Paperback

The Answer/LA Respuesta : Including a Selection of Poems- By Sor Juana Ines Dela Cruz, Sor Juana Cruz, Amanda Powell (Translator) 1994

- Paperback

Sor Juana’s Love Poems : In Spanish and English- By Juana Ines De LA Cruz, Joan Larkin (Translator), Jaime Manrique (Translator) 1997

- Paperback

- Sor Juana : A Trailblazing Thinker (Hispanicherit Age)

- By Elizabeth Coonrod Martinez. 1994

- Hardcopy

- Woman of Genius : The Intellectual Autobiography of Sor Juana De La Cruz

- Gabriel N. Seymour, Sor Juana Ines de La Cruz, Margaret Sayers Peden (Translator) 1982

- Paperback

- Early Modern Women’s Writing and Sor Juana Ines De LA Cruz

- By Stephanie Merrim, 1999

- Harcover