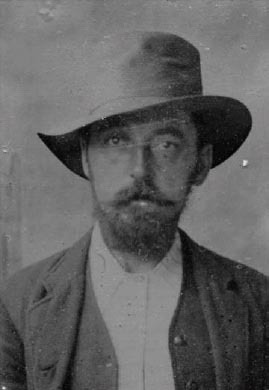

My grandfather, Frank Henry, was an English silver mining engineer in Mexico during the Revolution of 1910-16. This is the story of a family’s harrowing escape from marauding bandits at the height of the Revolution. Sadly, it was without my grandfather, as he had been brutally murdered by the bandits while defending their home from attack.

The British in 19th Century Mexico

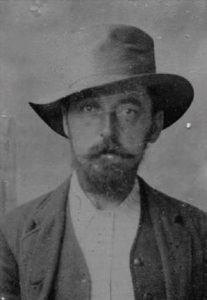

Frank was born in 1872, the son of an English rector. He took an English degree from London University and became a teacher. But the fire that burned in him was for geology and metals, and he went on to study mining. After two years on the Yukon Gold Rush and a spell in Southern California learning to operate a gold mine, he returned to England to explore his career options.

Back in England, Frank met Edith, and they were married in 1903, when Edith was twenty-seven and Frank thirty-one. Frank was very excited about the silver mining opportunities in Mexico, and applied for a position with a British mining company with holdings in Mexico. English emigration to Mexico was not uncommon in those days. England had played a leading role in Mexico’s modernization, and the British community there was several thousand strong.

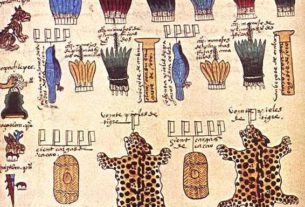

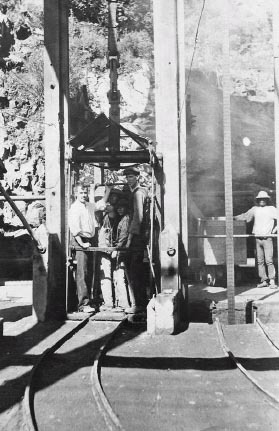

In particular, Britain had significant interests in the Mexican silver mining industry. Silver was the glory of Mexico. Vast silver deposits had been found in the mid-1500s and for centuries, Mexico ranked first in world silver production, generating immense wealth to line Spanish imperialist coffers.

The British Empire needed large quantities of this Latin American silver for its new trade with China and to back European paper currency in times of political instability. The weakening of the Iberian powers in the mid-18th century offered the opportunity for British expansion of its industrial interests into Mexico. In 1821, Mexico finally achieved independence from Spain. Britain was one of the first countries to grant recognition to the new state, and British companies were invited to explore the legendary wealth of the Mexican silver mines.

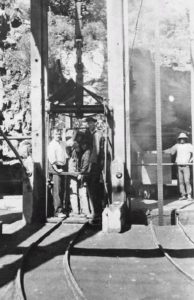

This was particularly attractive to British financiers, as English mining technology developed in the Cornish mines was by now leading the world in a rapidly expanding global mining economy. Major capital investment in the Mexican mines sparked the “Cornish Diaspora,” a migration by many thousands of highly skilled miners from Cornwall and west Devon to operate the silver mines. By 1826, one-third of the Mexican mines had Cornish directors. Railroads, financed with British and American capital in the 1880s, made it possible to transport huge amounts of ore, and silver output in Mexico grew immensely. The boom was on!

Frank’s qualifications were ideal for his prospective employer, and he was offered a position as an assayer in the Mexican mining town of Guanajuato. Edith was expecting their first child, and she was not at all sure this was the moment to be moving halfway across the world, to live in a desolate mining town in a completely foreign culture. But she wanted to support her husband’s dream, and his passion for mining was contagious.

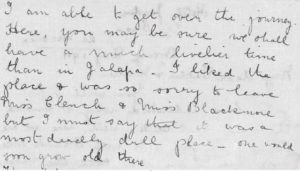

Frank went on ahead to organize accommodations, and Edith followed. The voyage from Liverpool took three weeks, and in March, 1905, together with the one year-old Ronald, they steamed into Veracruz harbor, enthusiastically looking forward to their adventures ahead. Edith wrote home:

Never have I seen or imagined such a colorful place. Coming from the unremitting grey of our English winter, the sunshine, warmth and flowers are welcome beyond belief.

Adjustment, though, was not so easy. A new language to be learned, customs to understand, a whole new culture to embrace. Besides, the life of a miner’s wife was very challenging. Frank would be gone to inaccessible mines for long stretches, leaving Edith alone in the mining camp with a few other miners’ wives for company. Soon, however, Edith was enjoying her new life in Mexico. Her second child, Jessie (who would become my mother) was born two years later in 1907. They were on the move frequently as Frank got better jobs at different mines. Money was tight, but the family flourished.

When the family arrived in 1905, the Revolution was five years away. Porfirio Diaz was still in power after 30 years, firmly implementing his policy of extensive foreign capital development. Under his regime, foreigners and the Mexican upper class minority who supported them lived splendidly on their haciendas and ranchos, while the great majority of Mexicans were poor agricultural workers, campesinos, who still lived under the thumb of the hacendados, often in peonage. Unfortunately, the Diaz economic reforms that had brought much-needed stability to the nation did not touch the lives of the Mexican working class. They were more oppressed than ever.

By 1910, Edith’s letters home noted the growing unrest in Mexico. The foreign community viewed it as local trouble that would soon be contained. They were wrong.

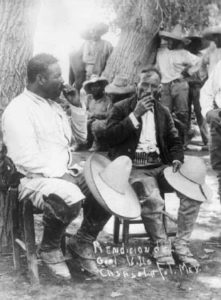

Kathleen was born in August, 1911. By this time, the Revolution was on in earnest. It began as a rebellion by rural Mexican villagers against the power elite, personified by the dictator Diaz, in an effort to reclaim land that had been forcibly taken from them by the hacendados. In November 1910, Francisco Madero, a young idealist from a wealthy family, supported by ragtag armies under Pancho Villa in the north and Zapata in the south, led a revolt against the Diaz administration.

By April, 1911, an estimated 17,000 Mexican workers had joined the revolutionary forces. The fighting was fierce everywhere and accompanied by urban riots and widespread looting by victorious troops. Edith wrote to her parents from Jalapa, near Veracruz:

You may be seeing in the paper that there has been fighting in Jalapa and you would be anxious about us. There has been trouble between Madero’s soldiers and the Federals. All the fighting was in the town — fortunately they did not come up this way. The hospital is overflowing with the wounded, 50 or more. The paper says 12 are dead, but I am told there were more.

Madero’s movement attracted such strong support among the people that he swept to victory. At the end of May, 1911, he unseated Diaz, and in June he entered Mexico City to the triumphant applause of quarter of a million people welcoming their nation’s new leader. But in reality Madero’s group was just a loose association of revolutionaries who wanted to defeat the dictatorial regime. Once that was accomplished, they could not agree on anything. Madero wanted steady and patient legal reform, while Villa’s and Zapata’s campaigns were aimed uncompromisingly at the immediate restoration of the land to the peasants. The alliance collapsed and the Villa and Zapata armies turned against the Madero government.

In 1912, within months of Madero’s coming to power, things began to seriously deteriorate. Every Mexican was involved in the Revolution, men, women and even children. Whole families were forced to join the rebel armies — or be killed. Many of the rich fled to the U.S., others tried to defend their property.

The main problem with the rebel armies was banditry. Zapata’s army controlled the west-central area where Frank and Edith lived. His inexperienced troops were undisciplined and beyond his control. Ruthless thugs in great bloodthirsty packs with no real leadership and calling themselves Zapatistas roamed the country, destroying and burning haciendas and ranches, grabbing and looting whatever they wanted, all under the umbrella of the Revolution. In November 1912, Frank wrote home:

All round this neighbourhood bands of Zapatistas are roving, occasionally entering and looting a small unprotected town and burning a few farm houses. They have even threatened our El Oro mine and all hands have had to turn out to drive them off.

Madero’s presidency lasted barely more than a year. He was a gentle and sincere man, whose dream for Mexico was democracy, not revolution, but he uncorked the wrong bottle! Too weak to sustain power, he was murdered in February 1913, at the instigation of his general, the Diaz old-liner Huerta, who was then installed as interim President. Violence exploded, as everyone hated Huerta.

The events galvanized Carranza, long-time defender of the Constitution and Madero’s secretary of war, into action. He founded a “Constitutional” movement to oust the reactionary Huerta, and took charge of the Constitutionalist Army as the national force for this purpose. Carranza was the “old man” of the Revolution, a model of patriarchal inflexibility, devoted only to serving the principle of authority. For him, the goal of the Revolution was to restore constitutional order, with the law reigning supreme. The Mexican novelist Martin Luis Guzman, working as a journalist at the time, described Carranza:

“He is not the hero, not the great altruistic politician that Mexico needs, but he knows how to be Premier Jefe.”

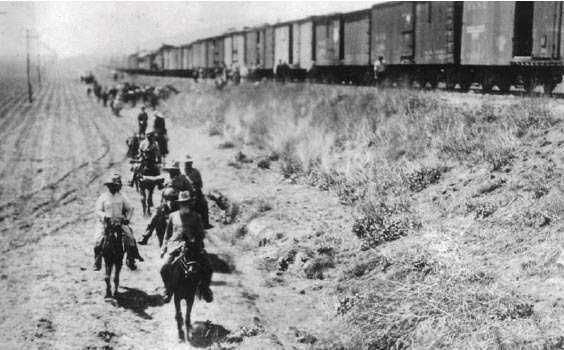

Despite their Jefe’s image of one who inspired obedience and order, the Constitutionalist Army, like the rebels under Villa and Zapata, were often undisciplined, more bandits than soldiers; they looted, murdered and raped with abandon. Trains were a big target for bandits and armies alike, and people dared not travel between cities. With the rapidly deteriorating economy, mines everywhere closed, and Frank found himself without work.

In the spring of 1914, finances forced the family to move to Mexico City where Frank tried other lines of work. There they witnessed the daily effects of the Revolution. The economy had collapsed and business was at a standstill, shops boarded up with prices soaring out of control. The mob looted, streets were unsafe, there were no police, no mail or communications. Bandits blocked all travel. Worst of all, there was no food and people were starving. Zapata and Carranza rebels surrounded the City trying to unseat the unpopular Huerta, and every day brought fierce fighting. In August 1914, Huerta surrendered, and Carranza declared himself President.

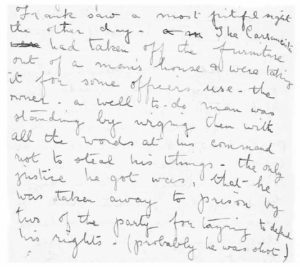

This did not help, and anarchy ruled as the unruly Carranza soldiers threw the Mexican moneyed classes out of their homes, and took whatever they pleased. Edith describes the scene:

The streets are full of these wild looking men; many of them have on as many as 6 belts, full of cartridges — and everyone carries a big knife in a sheaf as well as his gun. They are dirty and unshaven and unwashed, and all wear a dirty white shirt, with a towel or a red handkerchief twisted around the neck and a dirty pair of khaki trousers. Some wear uniforms much too large or too small for them — but they all wear the red and orange Carranza colours.

As with Madero, the problem for the Premier Jefe was his inability to get the two caudillos of the people, Villa and Zapata, to submit to his authority. For Carranza, the Zapatistas were rustic brigands, mere “rabble,” while Zapata denounced Carranza as a “corrupt cabrón surrounded by shyster lawyers,” simply another in a long line of machine politicians. With Villa, the problem was more along political lines, but equally intransigent.

By September 1914, Villa and Zapata had broken off all connection with Carranza. Nor did Zapata and Villa get along with each other. Zapata’s movement addressed only land ownership issues in his native state, Morelos. Villa was concerned with political revolt and the national transfer of power. The two rebel leaders had one single uncomfortable meeting, and never shared power. In November, Zapata’s armies forced Carranza out of Mexico City. The Carrancistas, supposedly the “torchbearers of civilization against barbarism,” had instead been mere vandals.

Foreigners were resented by the revolutionaries, but generally they were not the target of attack. An exception was the many American ranchers in northern states, especially Chihuahua and Durango, who when the fighting broke out were terrorized and robbed. American residents tended to be unpopular for several reasons. Historically, there was leftover bitterness over the annexation of Texas and California in 1846, most recently the U.S. ambassador played a disastrous role in Madero’s assassination by openly supporting Huerta, and America was begrudged as the largest foreign investor, owning 80% of all foreign holdings, so that while Americans could freely come in and find excellent work with these companies, such jobs were unavailable to even the best-educated Mexican. With Americans as targets for violence, the U.S. government urged its citizens to leave. Most of the European community, however, stayed on.

The Carrancistas and Zaps continued their violent fighting, looting and destruction, and things grew more dangerous everywhere. For the mining community, the added problem was a lack of work at the mines because the bandits were daily attacking trains and stealing dynamite and other supplies essential for operation of the mines. Frank and Edith soon found their savings exhausted, and they agonized over whether to give up on Mexico and go back to England. It was a hard decision, as mining work at home was nonexistent, but who knew when the mines in Mexico would reopen? Frank reluctantly conceded it was time to go.

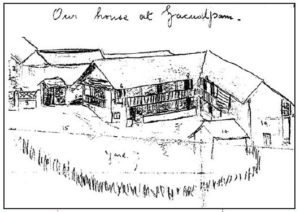

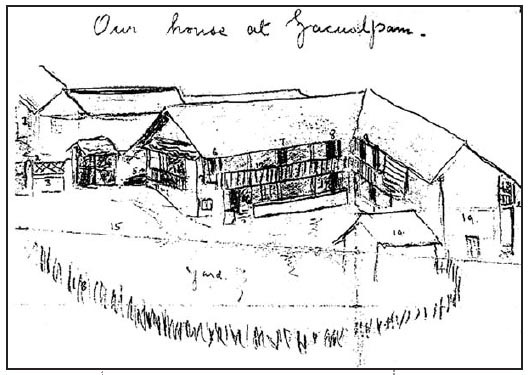

They were on the point of booking a passage, when Frank got hired as a mine superintendent at the San Miguel mine in Zacualpan, an ancient Aztec mining village in the mountains at the border of the states of Mexico and Guerrero, 100 miles southwest of Mexico City. The salary was not the best — but it was a job!

The journey was unforgettable. By train to Tenancingo, end of the branchline from the railhead at Toluca, and three days by mule up into the mountains through some of the most beautiful scenery imaginable. It was hair-raising too, as the trail wound into deep ravines and chasms so steep that no one ever rode down, and the animals just scrambled the best they could. Accommodations along the way were no luxury. The first night was bare dirt, the next a hayloft.

The Zacualpan days were the happiest for the family. The climate was warm and fresh, the town, an old Aztec center dating from before the 1500s, was beautiful with clear air and views for hundreds of miles over the mountains. The job came with a spacious adobe house. Edith was thrilled to be settling down at long last, especially into such a breathtaking place, albeit remote. Now Frank could be with his family all the time and not have to travel. Ronald was now twelve, Jessie eight and Kathleen four. Frank was a wonderful father, forever coming up with new games and things to do, keeping the children laughing and endlessly entertained. They adored him.

But Zacualpan had the same problems as everywhere else. Prices were impossible, food was in increasingly short supply and eventually there was nothing left in the shops. Tragically, people in the town were dying of hunger daily and succumbing to typhus, the national epidemic. Isolated and without newspapers or mail from the outside world, life nevertheless went on agreeably for Frank and Edith. Frank did very well in his new job, and the company quickly raised his salary. In particular, he was highly regarded by all the Mexican miners in the town under his management. There were struggles, such as the five-mile walk to the mine each day as the troops had commandeered all the mules, but everyone coped.

In October 1915, Carranza entered Mexico City once again by military victory. Villa and Zapata fought back, but suffered great losses. Conditions in Zacualpan suddenly worsened. Zapatista bandits came to the town every day to fight the Carrancistas there, looting as they went. Carranza soldiers were no better. They came to the house constantly demanding money and weapons. Frank strenuously resisted with guns, and kept them at bay. Frank and Edith knew they had to leave. But it was too dangerous to risk the three-day walk back to the railhead to get to Toluca. They were trapped.

Meantime, Frank was very keen to join the Allies at the front lines of the war in Europe where mining engineers were in hot demand. He applied, and assisted passage was recommended for them. But this was not to be.

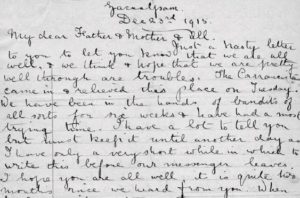

A detailed and vivid account of Frank’s tragic death at the hands of bandits as they stormed the garrison at Zacualpan, looting and killing, and her escape with the children, running for their lives day and night over the mountains to safety, survives as a letter written by Edith to her brother upon her arrival home in England that spring of 1916.

For about six weeks before Christmas of 1915 we had a very anxious time. Frank was much troubled, and we considered the ways and means of getting out. But it seemed impossible to get through so long a distance without animals to carry us. The Zapatistas had taken them all.

At last, a few days before Xmas, our Camp was relieved by the Carrancistas and the Zaps fled. The Carrancistas brought in such good news of the success of their army that we thought peace was at last come. They told us our part was the last bit of Mexico to be put in order. We did not need to leave after all. We had only them to believe, as there was no other way of getting news. The Carrancistas made joyful festivity with several dances and a large picnic.

All went well until the night of January 2nd. On January 1st Frank even took us out for a picnic to a nearby river and we had a glorious time. I brought out all the things I had hidden away — our most precious possessions. Everything was prosperous in Zacualpan, and with us.

It was 10 o’clock on Sunday evening, January 2nd. Suddenly, in rushed the Spaniard who lived nearby. Breathlessly, he told us, “The Carrancistas are going and are even now saddling up.” We considered what to do. The night was pitch dark and not a mule or donkey was to be had. In one hour they had all gone, and many people as well. Frank decided: “We will stay and brave it out as we have done before, but,” he said, “I would give 10 years of my life if only you and the children were in safety.”

The morning of January 3rd Frank got up long before breakfast and was out and about to see how things lay. There seemed nothing alarming, so we decided to make no move (we could have abandoned our things and house and taken to the hills). It was quiet, and though we felt uneasy, there were no signs of any Zapatistas near. However, at 1 o’clock, just as we were having lunch, a small band of them came into town, and soon we heard that looting had started in some houses.

Around 2.30 in the afternoon a band of six men came and demanded we open our door. Frank showed them the “salvo conducto” paper we had received from General Molino a month previously, stating we were not to be molested. They read it and went away apparently satisfied and we thought the danger was over.

After lunch we sat out on the verandah, Frank having a cigarette, I sewing and the children playing. Somehow, we got anxious even though no one came to tell us that more men were entering the town from all parts until at last they were at least 150 all told. Mr Odgers, the old Cornishman who lived nearby came rushing in saying that the bandits were at his house taking everything he had. He was almost beside himself. We comforted him all we could, and indeed were so busy with his troubles that we forgot our own nearly. We had a tiny amount of brandy I had saved, so I brought it — and Frank made Mr Odgers drink it all. But I could not help see a wistful look pass over Frank’s face as he did it, as if he would have given anything for a drink himself, but it was all we had.

Well, we were terribly worried, the guns had been brought out and examined that they were all right and put back into their hiding places.

“Well,” said Frank to Mr Odgers, “never mind, old man, we’ll look after you, and I have no doubt that you will have your chance soon to get back at them — you will shoot all the straighter for this, won’t you and make no mistake.” I remember this remark of Frank’s so well. “Ah! indeed I will,” said he, “You can depend upon me.” Feeling somewhat better, Mr. Odgers went off to deal with what was left in his house. We came to sit indoors and Frank got out the cards to try to distract himself with a game of patience. I sat beside him with my sewing; but we did not talk. I have found that the presence of danger nearly always makes one quiet.

Then I thought a cup of tea would do us all good, so I went out to the kitchen to see if the kettle was boiling. As I passed I looked up the hill and I saw there were men galloping down towards our house. I cried out to Frank, and an instant later in rushed Ronald: “Dada, they are outside tearing down our fence and starting to climb over.” Without a word to either of us, his face white and set, Frank rushed to get his gun. Ronald said: “I will go with you, Dada.” I cried out to him: “No, come in with me,” and Frank went out without a word to either of us, in a tremendous hurry, with the hand holding the gun behind his back so that it should not be seen until he had had time to speak with the bandits. I prepared to do my work just as we had always arranged together if it should happen. “Don’t speak to me as I shall be in too great a hurry to attend to you, but just gather the children together in the bedroom and stay quietly there until you hear further from me.” I did so and left the door ajar for easy access for Frank. That was the last time I saw Frank alive.

Then the shots rang out, a tremendous number of them, and the noise was terrific — of horses galloping down, running away, and hideous shouts from the bandits. The children screamed. The servant ran in — then I heard heavy footsteps on the balcony, and in rushed two men — bandits, who seized me by the arms. They yelled: “Where is your money?” and oh, so many words, cursing and furious they were — they pushed me: “Get out your things.” I got out my keys, my hands shook too much to open more than one drawer, but my jewelry and money were there. They grabbed and pushed over these, and were so busy that I unnoticed, ran out with the children. As we rushed onto the veranda — by this time the house was full of these men, and oh, I cannot tell you much more of what happened. They tore off my wedding ring — we were prisoners — a dozen guns were pointed at me — I tried to get out but was not allowed. I came back into one of the rooms — “Where is your husband?” they kept saying. I felt better. Frank must be alive yet I thought, but he must be wounded and someone has hidden him. They were all more or less drunk. They called us Americans — I said: “We are not, we’re English, that’s our flag,” and pointed at the Union Jack on our wall. “All the same,” they replied.

They demanded money and our weapons, and with the muzzle of a gun at my head I showed where the other two guns were, and where my silver teapot and a few other things were hidden. All this time Kathleen was screaming and trembling with fright. “If you have no pity for us, at any rate have pity on this poor little girl — have you no heart at all,” I asked them. They replied: “We want money.” “I have none — you have taken it all,” had no effect on them Plunder was all that was on their minds. Their beastly faces were shoved into mine, jeeringly — “Where is your husband?” General Molino, who had given us our salvo conducto, was with them, and he said: “How much will you pay me if I let you go?” I replied: “The men have already taken all I have.”

After I repeated this many times they seemed convinced it was true, and at last we were allowed to escape. As we rushed across the yard, a man tried to stop us — he lifted his gun to strike Ronald with the butt end. I saw it falling and pulled Ronald with all my might, and the man with the force of the blow fell over forward, but the gun had just caught Ronald’s arm.

We ran on to the gate to get out, and there I saw Frank just outside in the road stretched out. One glance showed me he was dead. He had been shot from behind right through the heart. Evidently he was just turning to slip back into the house when one man who had hidden himself in the house opposite, calmly waited for Frank to turn his back and then taken aim.

As I saw Frank I rushed forward and knelt down beside him. Many horses and a few men were there. One man leveled his gun at me, with his finger ready to shoot — “Touch him and we shoot” — I raised Frank’s hand to my lips, it was already cold and stiff. Then taking the children I rushed away to hide. I could do nothing for Frank now, and there were the children to save.

We wandered about dazed for a while. The town was like a dead town — not a soul to be seen, except the men carrying loot out of our house, and the noise of breaking up of other houses. Up the hill I saw our servant Leopoldo beckoning silently to us. We sat there in his house in the dark — Ronald hugging his injured arm, without one tear in his eyes, just silently without a word until nightfall. Then we stayed there for the night as we could not go to the house. I asked Leopoldo to go down to where Frank lay. “Take the Union Jack if it still hangs in our house and throw it over him and have a watch set over him.”

The bandits had taken off his coat and his boots, but fortunately he had on his mine clothes and so they did not care to take more — they rifled all his pockets; but missed his watch which was in a secret pocket in the belt of his trousers.

Early next morning I sent for Manuel Romero, Frank’s head miner who had sat up all night watching over Frank. I told Manuel to start making the coffin. We were every minute expecting the return of the Zapatistas, so I went down to see if I could recover Frank’s papers and plans of the mine. Then I sat by the side of Frank, he was still covered with the Union Jack — until the people near made me go. “The devils are back, they are just entering, go for your life.” And so I left him.

Then Manuel went to interview Molino. After trying to make Manuel tell him where we were hiding, and he insisted he knew not where we were, he gave leave that Frank could be buried. The coffin was ready about 1 o’clock. It was unpainted — there was no paint or varnish, but I liked it better so, and he was put in rolled up in the Union Jack, as I had asked — and carried by six of the miners. We could only watch from a distance above, hidden behind the verandah of our servant’s house, as Frank was carried up on his miners’ shoulders to the cemetery at the crest of the mountain. The bandits were too busy to molest Frank further, so they quietly buried him. I dared not go, as the bandits were busy all over the place, searching for loot and we were in much danger if we were found. Ronald’s arm was very bad, being badly bruised and dislocated, not broken but splintered at the elbow.

By now we were too dangerous for anyone to be with us. Faithfully however our servants took care of us, hiding us in a dark room the remainder of the day. Many times the bandits came to the house, but Leopoldo told them there was nothing except a bad case of typhus inside and so they did not enter.

The next day, Wednesday, the bandits did not return — though there were constant rumours of their returning to burn the place — they had cleared Zacualpan out entirely.

A man advised me of some people some distance away who were trying to escape to Toluca. They were sheltering with a rich ranch owner who had given much money to the Zapatistas and we might slip in among these ladies. Manuel said: “I will take you and not leave you until you are safe.”

The next morning we started off for this ranch which we reached after four hours walking. On the way, on leaving Zacualpan we visited Frank’s grave, and in the early morning said goodbye. He lies in a beautiful spot — under a tree — just outside the cemetery under its walls — the green grass very near to heaven it seemed.

We ran great risks in that part especially, and our party had to be divided up (we had one man carrying Kathleen on his back), to pass as silently and swiftly as possible. We reached the ranch house at 10:30 — only to find that we had walked right into the very nest of the bandits. Fortunately at that moment they were all away. They hurried us in, but then the people there told us we must go back, but Manuel said: “No, it is not possible, it is too risky and there is nothing to eat in Zacualpan. We must go forward, I will take them.”

But there in that house was all our loot and everything they had stolen from the entire village. And then they told us how the men had all come back on the night of January 3rd. All night the men were up dividing out the things and talking. They said: “They were frightened too, and talked about the reception Frank had given them and what had happened.” Suddenly there was a great commotion — Some of the bandits had returned, to get a stretcher. The man who had shot Frank had just been killed. He was stealing a woman out of her house and the husband heard the struggle and knifed him in a fight and he died. We hurried away before they could come in. God’s vengeance, it seemed to me, had been very swift.

We had a little donkey which the children took turns to ride — and we reached Estapah that night about 8.30. This was a village of huts made out of flattened tin, that we had seen so many times before all over Mexico. I will never forget the kindness of the Mexican Indians there who gave us shelter and food. All the nights we slept without any covering — right on the earth alongside the Indians who sheltered us.

The next morning at daybreak we started again and got to Tecaloya that afternoon about 4, where there was much fighting. The next day we crossed the Zapatista lines — having an escort. We lived on pulque and a few apples that day, much of the time we were running and then waiting in hiding for short intervals when we had to. We had no donkey this day. It was wonderful how Ronald and Jessie managed the journey. Jessie in slippers — only whimpered once, Ronald never made a single murmur only giving me his uninjured arm to help me up the steepest hills.

We reached Toluca that night. We looked like poor Mexicans, dirty, and in torn clothing, my hair down my back and a reboso on my head. Each night we slept without any covering, one night on the bare earth. But we had made it to safety. We took the train, and on Sunday we reached the City. Manuel was still with us.

By the time the train pulled into Mexico City, Edith had collapsed, seriously ill with typhus. For five weeks Edith lay in critical condition in the Lady Cowdray nursing home while the children were looked after by English families. By early March, she was ready to make the trip home. The British Consulate arranged for ship’s passage, and they returned to the tiny village of Sampford Spiney on Dartmoor.

In May 1917, Carranza officially became President. 1917 was worst year ever. The country was in ruins. Railroads were destroyed, mines closed, banks failed. Unemployment was staggering. Epidemics of typhus and flu spread, agriculture was catastrophic, hunger rampant.

In 1919, Zapata walked into a trap set by Carranza, and was shot dead in cold blood. The people rose up in arms at this treachery, and killed Carranza just outside Mexico City. Obregon succeeded to the Presidency, and violence ceased. Villa was finally gunned down by assassins in 1923.

The decade of violence in the name of the Revolution cost an estimated two million lives to war-related famine, disease, epidemic and combat — roughly one in eight Mexicans. With the exception of the horrible massacre of 17 U.S. miners in 1917 by a furious Villa lashing out at U.S. support of Carranza, Frank’s death was one of a small handful of British and American civilian casualties. The terrible toll was paid by the Mexicans themselves, and the leaders who fought for them.

As the Revolution came to an end, Edith corresponded with S. L. Lewis of the Republican Mining Co., on settlement of Frank’s death. Lewis’s letter captures exquisitely the enigmatic tragedy of war:

I returned from Zacualpan recently where I went in connection with the mine. The country is very beautiful now, with the rains, everything as green as it can be; one would hardly think, as one rides over it, that such things have happened here as we have seen.

Editor’s note: Much of this story originally appeared as “Murder in Mexico” in the June, 2004 edition of History Today.