Mexican History

How do we really know what happened in ancient Mexico before the arrival of the Spaniards and the introduction of writing?

Many articles and books have been written on the history of ancient Mexico from Prescott’s popular but biased Conquest of Mexico in 1521, to innumerable studies of the Aztecs, the Maya, and other indigenous folk in scholarly journals hidden in research libraries. Archaeologists have unearthed many a “vanished city” long hidden in the jungle, thus adding to our historical knowledge of the ancient civilizations of the Americas. Recent advances in the decipherment of the Maya hieroglyphs has led to a new historical interpretation of the information stored in inscriptions on stelae or stone markers at many Maya sites, such as the Temple of Inscriptions at Palenque. The still colourful murals at Bonampak tell us much about warfare among the ancient Maya. Painted ceramic artefacts too add to our knowledge of historical events before the Spanish conquest.

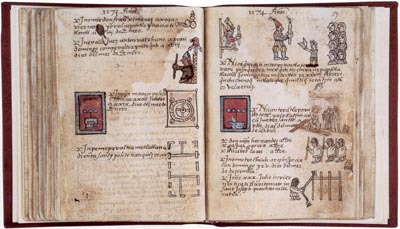

However, as important as these discoveries are, it is still outside knowledge collected by researchers and writers who did not participate in any of the events recorded. To get an idea how the Indians actually viewed these events we must turn to the pictorial and “written” manuscripts or codices produced by the people themselves. The codices themselves were generally in the form of long strips of native paper (amatl) or sized deerskin folded up into the shape of a moderate sized book, hence the name codex. Others were originally produced in book format.

The late Maya scholar E. Thompson thought it was time to forgive Bishop Landa for destroying so many painted Maya books in the infamous bonfire at Mani because he left us his Relación de las cosas de Yucatan, a main primary source on the Maya. However, when we examine the contents of the remaining codices, we begin to realize just how much valuable historical evidence has been irretrievably lost. Only four Maya codices remain and two possibly pre-Hispanic Aztec codices. Other pre-Conquest codices include the Borgia Codex painted in the Mixteca-Puebla style and a handful of Mixtec codices from the Oaxaca area. However, native indigenous writers and painters continued to produce these manuscripts long after the Conquest during the colonial period of Mexico, thus providing us with a vivid picture of Indian life under Spanish domination along with tantalizing glimpses back into the pre-Hispanic past.

The Codez Aubin Tonalamatl and the Tonalamatl of the Codex Borbonicus are two surviving Aztec codices that may be pre-Hispanic in date.

The Aubin Codex

The Aubin Codex contains 18 screen-fold pages and is made out of 13 bark pieces pasted together, probably came from the Mexican state of Tlaxcala. The recent history of this codex illustrates the hazards through which many of these documents have passed before reaching us in their present state. The Aubin Codex was sold several times before being legally exported to France in the 19th century, where it was deposited in the National Museum of Paris. This was the fate of most of the codices that were spared the cultural holocaust of the Spanish Conquest. Had these valuable manuscripts not been sent out of Mexico to various European cities they would undoubtedly have been lost.

In 1982, a patriotic Mexican by the name of Jose Luis Castañeda del Valle went to France, passed himself off as a student, and asked permission to see the Aubin Codex. He then calmly put it under his coat and walked out of the Paris Museum and returned to Mexico, where he donated it to the library of the National Institute of Anthropology and History. When arrested for the theft, he claimed that he had acted in the best interests of Mexico by repatriating a national treasure. Of course he was exonerated and the Mexican government promptly modified the law protecting archaeological artefacts to include codices. Naturally the French authorities wanted it back but an agreement was worked out to be reviewed every three years. The Aubin Codex is currently on permanent “loan” to the Mexican Institute. That way everyone saved face.

The Codex Borbonicus

The Codex Borbonicus is a pre-Hispanic or early 16th century ritual-calendrical codex from the Mexico City area. Painted on native paper, it comprises 36 leaves and contains later glosses (explanations) in Spanish. This type of codex is called a Tonalamatl (tonalli, or “birth sign” and amatl, or “paper”) or Tonalpohualli (count of the days), which serves as a guide to the numerous fiestas of the ancient Aztec calendar.

The Tonalamatl of the Codex Borbonicus, therefore, represents the 260-day sacred calendar as it intermeshed with the secular year of 360 days + 5 “unlucky days.” For example, the main panel for the Fourth Week, day one (named Xochitl, or “Flower”) shows the presiding god Huehuecoyotl (Old Coyote) accompanied by a figure playing a drum. Various other deities and symbols associated with each day are shown in the side panels, namely the 13 Lords of the Day, the 9 Lords of the Night, and the accompanying symbolic bird of each day in compartments below and to the right of the main panel. This pattern is repeated throughout the 20 weeks of the calendar.

The Codex Columbino

The Codex Columbino is of special importance because not only is it (reportedly) just about the only pre-Hispanic codex left in Mexico, but it is also thought to be the oldest of the Mixtec codices. Originally there were seven fragments of this codex, which were late combined into three sections. At first it was thought to be related to the Codex Becker I, which was thus named after the German who re-discovered it after it disappeared in 1854. It was probably composed in the 13th century but then became separated from the Codex Columbino around 1541. The Mexican scholar Alfonso Caso (1896-1970) finally demonstrated conclusively that this part originally belonged to the Codex Columbino, thus reuniting the fragments. Accordingly, it became known as Codex Columbino-Becker I but was later renamed the Alfonso Caso Codex in honour of Caso. Such are the sometimes fragile connections that link modern Mexico to its pre-Hispanic past.

At first scholars thought that the Codex Columbino-Becker I was a ritual calendar dealing only with the dates of various fiestas and religious ceremonies. This appeared to be confirmed by the famous German scholar E. Seler, who declared it a religious or mythological document. A later investigator, E. Castellanos, while badly misinterpreting parts of it, realized that it was basically a historical narrative. A. Caso worked out the genealogies of the ancient kings and queens of the Mixtec peoples of southern Oaxaca from his analysis of the Mixtec codices. We now know that this codex is simply one of several of the extant pre-Hispanic Mixtec codices that deal with the life and times of the most famous of the Mixtec warrior-kings, 8 Deer Tiger Claw.

Religious ceremonies and rituals are often represented in these codices but it is clear that we are also dealing with genuine native history. However, in order to see things from the native point of view, we must first rid ourselves of certain preconceptions about how history should be written. In ordinary daily life, if six people describe the same event each from his or her own perspective, we will get six different versions of the same event. Of course there will be certain features common to all the descriptions but there will almost certainly be significant differences between one account and another.

Different Voices, Differing Stories

Deep cultural and linguistic differences existed between the Aztecs and the Spanish invaders at the time of the Conquest. For example, the Aubin Tonalamatl and the Borbonicus Tonalamatl present a view of sacred or cyclical time that would have been all but incomprehensible to the invaders. Furthermore, not only were the Aztecs and the Spaniards far apart in their world outlook but their respective motives for recording or writing history were completely different as well. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the Indians and the Spaniards ended up with almost diametrically opposed views of the historical events in which they were involved. It is true that Spanish missionary-historians, such as Durán and Sahagún, left us detailed descriptions of the numerous ceremonies associated with the sacred calendar but they did so solely for the purpose of destroying these supposedly heathen beliefs in the cause of converting the natives to Christianity.

According to the Codex Boturini and other primary sources, the Mexica (later the Aztecs) set out on their pilgrimage in search of a new homeland led by their war god Huitzilopochtli. The entire heroic saga contains many elements we may regard as mythical or fictitious.

However, comparative studies of other world-wide epic traditions confirm the historical basis of many epic poems and sagas that would otherwise be regarded as sheer fiction. Likewise, there is an underlying basis of historical truth in the Nahuatl texts written after the Conquest that suggests the Aztecs had a strong epic tradition in pre-Hispanic Mexico. The Mexicans too had their ancient Heroic Age.